Don't Look Back

Don't Look BackPart Two

OK, folks, it's hard to believe it was over a year ago that I promised you a second installment of the Bobby Womack saga, but time flies when you're having fun, I guess... When we last left our hero, he was taking a lot of heat for marrying Sam Cooke's widow, and was unable to get his records played on the radio, as the disk jockeys that had known and loved Sam were 'throwing his records in the garbage'. Releases on the Him label and Fred Smith's Keymen Records went nowhere, and Bobby was itching to get back to work. In 1965, he auditioned for a spot in Ray Charles' band.

When we last left our hero, he was taking a lot of heat for marrying Sam Cooke's widow, and was unable to get his records played on the radio, as the disk jockeys that had known and loved Sam were 'throwing his records in the garbage'. Releases on the Him label and Fred Smith's Keymen Records went nowhere, and Bobby was itching to get back to work. In 1965, he auditioned for a spot in Ray Charles' band. Ray was reportedly amazed by the fact that Bobby could keep up with him, no matter what changes he called, without being able to read the music they had set in front of him. "My music is way more complicated than Sam Cooke's stuff," Ray told him, but in spite of that, Womack was hired. He spent the next year or so out on the road with Brother Ray, playing over 200 dates a year. Conditions were less than rosy, however, and Bobby, as the newest member of the outfit, had to take the brunt of it.

Ray was reportedly amazed by the fact that Bobby could keep up with him, no matter what changes he called, without being able to read the music they had set in front of him. "My music is way more complicated than Sam Cooke's stuff," Ray told him, but in spite of that, Womack was hired. He spent the next year or so out on the road with Brother Ray, playing over 200 dates a year. Conditions were less than rosy, however, and Bobby, as the newest member of the outfit, had to take the brunt of it. From ill fiiting hand-me-down uniforms, to doubling up in hotel rooms with the epileptic Curtis Aimey, Bobby seemed to be the last one on the list. The thing that finally got him fired, however, was that he complained about the fact that Ray would fly the band's plane himself. "Man, I couldn't sleep for thinking about our flights between gigs," Bobby said, "...a blind man was flying the plane. I had attacks about that." Incredible. Ray fired him in early 1967.

From ill fiiting hand-me-down uniforms, to doubling up in hotel rooms with the epileptic Curtis Aimey, Bobby seemed to be the last one on the list. The thing that finally got him fired, however, was that he complained about the fact that Ray would fly the band's plane himself. "Man, I couldn't sleep for thinking about our flights between gigs," Bobby said, "...a blind man was flying the plane. I had attacks about that." Incredible. Ray fired him in early 1967. According to the liner notes of Atlantic Unearthed: Soul Brothers, Bobby's lone session for Atlantic was held in September of 1966. When Atlantic 2388 was released in early 1967, his last name had been misspelled as 'Wommack'. As you may recall, that same spelling had been used on the writer's credit for the first song he gave to Wilson Pickett, Nothing You Can Do, which was recorded at Fame in Muscle Shoals. I'm guessing that Bobby's single was recorded there as well.

According to the liner notes of Atlantic Unearthed: Soul Brothers, Bobby's lone session for Atlantic was held in September of 1966. When Atlantic 2388 was released in early 1967, his last name had been misspelled as 'Wommack'. As you may recall, that same spelling had been used on the writer's credit for the first song he gave to Wilson Pickett, Nothing You Can Do, which was recorded at Fame in Muscle Shoals. I'm guessing that Bobby's single was recorded there as well. It was Pickett who told him about the studio in Memphis he was headed to next... "Bobby," he said. "there are some white boys down there; if you closed your eyes, you could not tell they weren't black. Those f#*@ers can play!" The studio he was referring to, of course, was American Sound, and in July of 1967, Bobby Womack flew into town, installed himself into the Trumpet Motel, and showed up at American for Pickett's first sessions there. In addition to playing guitar, he brought along another one of his compositions, the amazing I'm In Love, which The Wicked One would take to #6 R&B later that year. When Pickett left, Bobby stayed on, becoming an integral member of the 'American Group' during its absolute heyday.

It was Pickett who told him about the studio in Memphis he was headed to next... "Bobby," he said. "there are some white boys down there; if you closed your eyes, you could not tell they weren't black. Those f#*@ers can play!" The studio he was referring to, of course, was American Sound, and in July of 1967, Bobby Womack flew into town, installed himself into the Trumpet Motel, and showed up at American for Pickett's first sessions there. In addition to playing guitar, he brought along another one of his compositions, the amazing I'm In Love, which The Wicked One would take to #6 R&B later that year. When Pickett left, Bobby stayed on, becoming an integral member of the 'American Group' during its absolute heyday. "...no one bothered me there. No one asked me about Sam Cooke or nothing... they just knew me as Bobby Womack, guitar player," he said, "It was the place to be, I loved the atmosphere, and there was a little soul-food place around the corner. Perfect." His serious chops got him accepted right away, "I was especially good at the intros. That's what made Moman and the others notice me... they called me cold-blooded, the way I could slip a guitar break in to make a track sing. Give a crafty hook to the intro, something people don't forget."

"...no one bothered me there. No one asked me about Sam Cooke or nothing... they just knew me as Bobby Womack, guitar player," he said, "It was the place to be, I loved the atmosphere, and there was a little soul-food place around the corner. Perfect." His serious chops got him accepted right away, "I was especially good at the intros. That's what made Moman and the others notice me... they called me cold-blooded, the way I could slip a guitar break in to make a track sing. Give a crafty hook to the intro, something people don't forget." All of these quotes are taken from the fascinating autobiography Bobby published last year, Midnight Mover: The True Story Of The Greatest Soul Singer In The World. In the book he describes the American Group as "a strong house band, with Bobby Emmons on keyboards, Tommy Cogbill on Bass, Bobby Wood the piano player, drummer Gene Chrisman, and Mike Leech who also played bass and arranged strings." No mention of Reggie Young, though... When Barney Hoskyns asked Chips Moman about Womack in those days, he said "He and Reggie played guitar together for a couple of years there, and the two of them would be just magic, alternating between lead and rhythm, and getting each other's playing down totally." That sounds about right, and I think the friendly competition between the two guitarists created something more than the sum of its parts. Chips saw that, and was happy to have Bobby on board.

All of these quotes are taken from the fascinating autobiography Bobby published last year, Midnight Mover: The True Story Of The Greatest Soul Singer In The World. In the book he describes the American Group as "a strong house band, with Bobby Emmons on keyboards, Tommy Cogbill on Bass, Bobby Wood the piano player, drummer Gene Chrisman, and Mike Leech who also played bass and arranged strings." No mention of Reggie Young, though... When Barney Hoskyns asked Chips Moman about Womack in those days, he said "He and Reggie played guitar together for a couple of years there, and the two of them would be just magic, alternating between lead and rhythm, and getting each other's playing down totally." That sounds about right, and I think the friendly competition between the two guitarists created something more than the sum of its parts. Chips saw that, and was happy to have Bobby on board. Womack also became a regular member of Wilson Pickett's touring band, and has some stories to tell about that whole experience. As Pickett travelled back to Muscle Shoals to record, Bobby made the trip with him, supplying much of his material in the process. All in all, Wilson recorded some seventeen Womack compositions (like I'm A Midnight Mover and I Found A True Love), and Bobby was happy to sit back and collect the publishing checks.

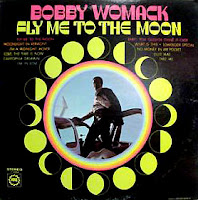

Womack also became a regular member of Wilson Pickett's touring band, and has some stories to tell about that whole experience. As Pickett travelled back to Muscle Shoals to record, Bobby made the trip with him, supplying much of his material in the process. All in all, Wilson recorded some seventeen Womack compositions (like I'm A Midnight Mover and I Found A True Love), and Bobby was happy to sit back and collect the publishing checks. Before he left California, however, Bobby had signed with Minit Records, after playing some of his songs for them as demos. They told him to go out and record something, and that they'd be happy to release it. After a couple of years of putting them off, Minit was finally looking for some 'product', only Bobby had given all of his originals away to Pickett. He started fooling around with a few standards with the guys in the studio, and the album that Minit finally received contained covers of Fly Me To The Moon, Moonlight In Vermont and California Dreamin'. They were none too thrilled.

Before he left California, however, Bobby had signed with Minit Records, after playing some of his songs for them as demos. They told him to go out and record something, and that they'd be happy to release it. After a couple of years of putting them off, Minit was finally looking for some 'product', only Bobby had given all of his originals away to Pickett. He started fooling around with a few standards with the guys in the studio, and the album that Minit finally received contained covers of Fly Me To The Moon, Moonlight In Vermont and California Dreamin'. They were none too thrilled. Much to everyone's surprise (except Bobby's, of course), Fly Me To The Moon became a big hit, breaking into the R&B top twenty in the summer of 1968. California Dreamin' would do the same for the company that fall. Womack was onto something, and they let him run with it. When Womack covered a song, it became something else entirely. He made each one his own. Hoping to continue in that vein, his version of I Left My Heart In San Francisco was released as a single in early 1969, but only managed to dent the top fifty.

Much to everyone's surprise (except Bobby's, of course), Fly Me To The Moon became a big hit, breaking into the R&B top twenty in the summer of 1968. California Dreamin' would do the same for the company that fall. Womack was onto something, and they let him run with it. When Womack covered a song, it became something else entirely. He made each one his own. Hoping to continue in that vein, his version of I Left My Heart In San Francisco was released as a single in early 1969, but only managed to dent the top fifty. The album it was taken from, My Prescription, is often overlooked, but represents, in my opinion, some of the best stuff to ever emanate from 827 Thomas Street. Minit would pull three more singles from the album for release in 1969 and early 1970. All of them charted, with How I Miss You Baby climbing as high as #14 R&B. Then the company went out of business... more accurately, it was 'consolidated' by the corporate conglomerate that owned it (like the once mammoth Imperial label before it) into its parent company, Liberty Records.

The album it was taken from, My Prescription, is often overlooked, but represents, in my opinion, some of the best stuff to ever emanate from 827 Thomas Street. Minit would pull three more singles from the album for release in 1969 and early 1970. All of them charted, with How I Miss You Baby climbing as high as #14 R&B. Then the company went out of business... more accurately, it was 'consolidated' by the corporate conglomerate that owned it (like the once mammoth Imperial label before it) into its parent company, Liberty Records. Looking for more of the same, Liberty would release one more single from this mighty Minit Lp, I'm Gonna Forget About You. Written by Womack's mentor Sam Cooke, it would become an R&B top thirty hit in the summer of 1970. Today's positively infectious B side was the flip of that single. Originally written by Smokey Robinson for the Temptations in 1965, it had become Paul Williams signature song, and closed out many a Temps performance. This version is better. Way better. Let me just say here that in all the time I've been doing this, this has to be the absolute BEST RECORD I've ever put up here. I mean it, boys and girls. The unbelievable Chips Moman production, Bobby's soulful vocals, the interplay of the guitars, the organ, the drums, the cookin' bass line... like the label says, it's 'An American Group Production', this time for one of their own, and was recorded around the same time that Elvis was in the building. It just doesn't get any better.

Looking for more of the same, Liberty would release one more single from this mighty Minit Lp, I'm Gonna Forget About You. Written by Womack's mentor Sam Cooke, it would become an R&B top thirty hit in the summer of 1970. Today's positively infectious B side was the flip of that single. Originally written by Smokey Robinson for the Temptations in 1965, it had become Paul Williams signature song, and closed out many a Temps performance. This version is better. Way better. Let me just say here that in all the time I've been doing this, this has to be the absolute BEST RECORD I've ever put up here. I mean it, boys and girls. The unbelievable Chips Moman production, Bobby's soulful vocals, the interplay of the guitars, the organ, the drums, the cookin' bass line... like the label says, it's 'An American Group Production', this time for one of their own, and was recorded around the same time that Elvis was in the building. It just doesn't get any better.Wow.

Liberty would release a live album, as well as one last single on Bobby before being 'consolidated' right out of business itself in 1971, when something called The TransAmerica Corporation rolled it over into United Artists. The new label would release another single from the live album, one that was responsible for giving Bobby his nickname, The Preacher, as he told it like it was over both sides of the 45, just like he did at the end of his live shows.

Liberty would release a live album, as well as one last single on Bobby before being 'consolidated' right out of business itself in 1971, when something called The TransAmerica Corporation rolled it over into United Artists. The new label would release another single from the live album, one that was responsible for giving Bobby his nickname, The Preacher, as he told it like it was over both sides of the 45, just like he did at the end of his live shows. Bobby, although he never changed anything, now found himself at his third record label in two years. As it turned out, that wasn't so bad, as the people at United Artists seemed willing to listen, and gave him creative control over his releases. 1971 was also the year that he collaborated with Gabor Szabo and came up with the immortal Breezin'. Bobby also began working with Sly Stone, and appeared on his groundbreaking There's a Riot Going On album. It was Sly who convinced him to lose the suit, and came up with the idea for the cool cover shot on his first UA album, Communication. In many ways, this was the record that kind of defined what Womack, and much of black music in the seventies, was all about. The title track would hit the R&B top forty, but the next single off the album, That's The Way I Feel About 'Cha, became his biggest hit yet, climbing to #2 R&B in December of 1971.

Bobby, although he never changed anything, now found himself at his third record label in two years. As it turned out, that wasn't so bad, as the people at United Artists seemed willing to listen, and gave him creative control over his releases. 1971 was also the year that he collaborated with Gabor Szabo and came up with the immortal Breezin'. Bobby also began working with Sly Stone, and appeared on his groundbreaking There's a Riot Going On album. It was Sly who convinced him to lose the suit, and came up with the idea for the cool cover shot on his first UA album, Communication. In many ways, this was the record that kind of defined what Womack, and much of black music in the seventies, was all about. The title track would hit the R&B top forty, but the next single off the album, That's The Way I Feel About 'Cha, became his biggest hit yet, climbing to #2 R&B in December of 1971. His next album, Understanding, was released in 1972. Just a fantastic record, Bobby Womack's genius is fully realized here for the first time. Establishing him as the R&B superstar Sam Cooke had envisioned he was destined to become, there was no turning back. One of the last albums to be recorded at American before Moman closed it down, it was produced by Womack himself, and it shows. Two 45s were taken from the album, resulting in no less than three chart hits.

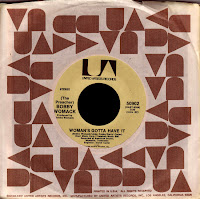

His next album, Understanding, was released in 1972. Just a fantastic record, Bobby Womack's genius is fully realized here for the first time. Establishing him as the R&B superstar Sam Cooke had envisioned he was destined to become, there was no turning back. One of the last albums to be recorded at American before Moman closed it down, it was produced by Womack himself, and it shows. Two 45s were taken from the album, resulting in no less than three chart hits. The first of these, the timeless Woman's Gotta Have It, became Bobby's first #1 hit in April of 1972. Speaking to the ladies in the audience (another thing he had learned from Sam), they let him know that all was forgiven. The Womack was back. Both sides of his next single would chart, with Harry Hippie (reportedly written about his ill-fated brother, Harris Womack) going top ten, and Sweet Caroline (which he had no doubt been a part of when Neil Diamond cut the original at American) top twenty...

The first of these, the timeless Woman's Gotta Have It, became Bobby's first #1 hit in April of 1972. Speaking to the ladies in the audience (another thing he had learned from Sam), they let him know that all was forgiven. The Womack was back. Both sides of his next single would chart, with Harry Hippie (reportedly written about his ill-fated brother, Harris Womack) going top ten, and Sweet Caroline (which he had no doubt been a part of when Neil Diamond cut the original at American) top twenty... I think we'll leave the rest of the Bobby Womack story for another day. There's plenty more to tell, believe me.

I think we'll leave the rest of the Bobby Womack story for another day. There's plenty more to tell, believe me.One can only hope it doesn't take me as long this time to get around to telling it...

No comments:

Post a Comment