The Triumphs - Raw Dough (Volt 100)

Raw Dough

Raw DoughLincoln Wayne Moman.

That's his name. Like some solitary figure out of the old west, you never know where he might turn up. Just when you think you know him, you find out that maybe you didn't know him after all, and he's on his way out of town. Enigmatic, elusive, he travels alone. According to popular legend, his nickname 'Chips' refers to his fondness for the game of Poker. A game that requires artifice and skill. A game that may be, after all, the key to understanding this reclusive giant of American Music.

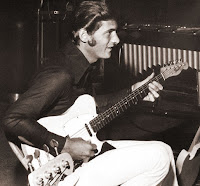

That's his name. Like some solitary figure out of the old west, you never know where he might turn up. Just when you think you know him, you find out that maybe you didn't know him after all, and he's on his way out of town. Enigmatic, elusive, he travels alone. According to popular legend, his nickname 'Chips' refers to his fondness for the game of Poker. A game that requires artifice and skill. A game that may be, after all, the key to understanding this reclusive giant of American Music. He grew up in rural LaGrange, Georgia, south of Atlanta. As he told Allen Smith, "I played guitar ever since I could remember, really... it seems like I had always played guitar." His mother , he says, started him off on the ukelele, before getting him his first real guitar from Sears and Roebuck, a Gene Autry model. When he was 14 years old, he up and hitch-hiked to Memphis. That was in 1950. Staying with his aunt, he took to painting houses to earn a few dollars, while he continued to learn to play on the borrowed guitars of his friends from the neighborhood. "None of us knew what we were doing," he said, "we just got together and kind of played a little bit." He spent much of his teenage years out on the road, hustling jobs wherever he could find them, continuing to play in pick-up bands whenever he got the chance.

He grew up in rural LaGrange, Georgia, south of Atlanta. As he told Allen Smith, "I played guitar ever since I could remember, really... it seems like I had always played guitar." His mother , he says, started him off on the ukelele, before getting him his first real guitar from Sears and Roebuck, a Gene Autry model. When he was 14 years old, he up and hitch-hiked to Memphis. That was in 1950. Staying with his aunt, he took to painting houses to earn a few dollars, while he continued to learn to play on the borrowed guitars of his friends from the neighborhood. "None of us knew what we were doing," he said, "we just got together and kind of played a little bit." He spent much of his teenage years out on the road, hustling jobs wherever he could find them, continuing to play in pick-up bands whenever he got the chance. By the time he turned twenty, he was back in Memphis. Rockabilly pioneer Warren Smith heard him playing one of those borrowed guitars one day in a local drugstore, and hired him on the spot to play in his band (I guess he must have been pretty good by then). As Smith went on to record at Sun, Chips was in the middle of it all, beginning his long association with the Memphis studio scene right there on the ground floor. He earned his reputation as a 'guitar-slinger for hire' in those days, playing with Smith all over the South.

By the time he turned twenty, he was back in Memphis. Rockabilly pioneer Warren Smith heard him playing one of those borrowed guitars one day in a local drugstore, and hired him on the spot to play in his band (I guess he must have been pretty good by then). As Smith went on to record at Sun, Chips was in the middle of it all, beginning his long association with the Memphis studio scene right there on the ground floor. He earned his reputation as a 'guitar-slinger for hire' in those days, playing with Smith all over the South. After Memphis brothers Dorsey and Jimmy Burnette hit it big (along with Paul Burlison) on Ted Mack's amateur hour up in New York as The Rock and Roll Trio, they needed someone to go out on the road with them in support of their records. They hired Chips to play with them on a tour that would take them out to California. It was here, at the legendary Gold Star Studios, that he got his first work as a session guitarist. Intrigued by the whole process of 'making records', he knew he had found his calling.

After Memphis brothers Dorsey and Jimmy Burnette hit it big (along with Paul Burlison) on Ted Mack's amateur hour up in New York as The Rock and Roll Trio, they needed someone to go out on the road with them in support of their records. They hired Chips to play with them on a tour that would take them out to California. It was here, at the legendary Gold Star Studios, that he got his first work as a session guitarist. Intrigued by the whole process of 'making records', he knew he had found his calling. While out on the road with Gene Vincent and Gary Stites, the young Moman was in a car accident that sidelined him for a while, and he returned to Memphis. He got a job playing in Ray Scott's band (whose claim to fame remains being the author of Billy Lee Riley's Flying Saucers Rock and Roll), a band that also included a drummer named Gene Chrisman. In that crazy world of 1950s Memphis, a barber named M.E. Ellis (who had also opened his own record company... didn't everybody?), introduced Chips to one of his customers, this guy that worked in a bank, and was trying to get his own little studio and record label (Satellite), up and running. His name was Jim Stewart.

While out on the road with Gene Vincent and Gary Stites, the young Moman was in a car accident that sidelined him for a while, and he returned to Memphis. He got a job playing in Ray Scott's band (whose claim to fame remains being the author of Billy Lee Riley's Flying Saucers Rock and Roll), a band that also included a drummer named Gene Chrisman. In that crazy world of 1950s Memphis, a barber named M.E. Ellis (who had also opened his own record company... didn't everybody?), introduced Chips to one of his customers, this guy that worked in a bank, and was trying to get his own little studio and record label (Satellite), up and running. His name was Jim Stewart. Stewart and a couple of partners were recording in his uncle's garage using some primitive equipment they had borrowed from Ellis. They wanted to cut a record on a woman named Donna Rae, who was somewhat of a local personality, hosting Wink Martindale's 'Dance Party' TV show every week (that's ol' Wink on the show with another guy from Memphis at left). Chips convinced Ray Scott to come up with a couple of songs for her, on the condition that Jim let Ray make his own record at no cost. No problem. Chips played guitar on the Donna Rae record there in the garage in 1958. It didn't sell. Neither did Scott's.

Stewart and a couple of partners were recording in his uncle's garage using some primitive equipment they had borrowed from Ellis. They wanted to cut a record on a woman named Donna Rae, who was somewhat of a local personality, hosting Wink Martindale's 'Dance Party' TV show every week (that's ol' Wink on the show with another guy from Memphis at left). Chips convinced Ray Scott to come up with a couple of songs for her, on the condition that Jim let Ray make his own record at no cost. No problem. Chips played guitar on the Donna Rae record there in the garage in 1958. It didn't sell. Neither did Scott's. Convinced he needed better equipment, Stewart talked his sister, Estelle Axton, into mortgaging her house so she could lend him the money to buy a new Ampex machine. He bought out his other partners at that point, and set up shop in an empty storefront outside of the city, in Brunswick, Tennessee. With basically no clue what to do next, he asked Chips (and a friend named Jimbo Hale) to help him set it up.

Convinced he needed better equipment, Stewart talked his sister, Estelle Axton, into mortgaging her house so she could lend him the money to buy a new Ampex machine. He bought out his other partners at that point, and set up shop in an empty storefront outside of the city, in Brunswick, Tennessee. With basically no clue what to do next, he asked Chips (and a friend named Jimbo Hale) to help him set it up.Moman looked at the cards in his hand... not much there, really. Here was an opportunity to raise the stakes a little. What kind of ante had Stewart thrown into the pot? What promises were made? I don't know, but Chips was in.

With him on guitar and Jimbo on bass, they brought in Jerry 'Satch' Arnold on drums, providing Stewart with his first rudimentary rhythm section. The first release from the new studio was on a black vocal group called The Veltones that local music figure Earl Cage brought out to record. Although it was picked up for national distribution by Mercury in mid 1959 (much to everyone's amazement), it went nowhere. Ditto for the fledgling company's next record, cut on an incredible singer that Chips had brought out there himself, one Charles Heinz.

With him on guitar and Jimbo on bass, they brought in Jerry 'Satch' Arnold on drums, providing Stewart with his first rudimentary rhythm section. The first release from the new studio was on a black vocal group called The Veltones that local music figure Earl Cage brought out to record. Although it was picked up for national distribution by Mercury in mid 1959 (much to everyone's amazement), it went nowhere. Ditto for the fledgling company's next record, cut on an incredible singer that Chips had brought out there himself, one Charles Heinz. The Brunswick thing wasn't working out, and everyone knew it. Chips was on it. He knew that they had to get back into the thick of things to make it work. Familiar with the acoustics at Royal Studio, which had been built into an old movie theater the year before, Chips looked all over the city for a suitable location. He found it, pretty much around the corner, in the empty Capitol Theater on McLemore Avenue. "I wanted it in a black community," he told Rob Bowman, "that's the music that I wanted to do." It was that decision that basically created Soul music as we know it today.

The Brunswick thing wasn't working out, and everyone knew it. Chips was on it. He knew that they had to get back into the thick of things to make it work. Familiar with the acoustics at Royal Studio, which had been built into an old movie theater the year before, Chips looked all over the city for a suitable location. He found it, pretty much around the corner, in the empty Capitol Theater on McLemore Avenue. "I wanted it in a black community," he told Rob Bowman, "that's the music that I wanted to do." It was that decision that basically created Soul music as we know it today. As they renovated and got things set up, Estelle opened a record shop in what used to be the lobby. People came in off the street to see what was going on. People like a 16 year old Booker T. Jones, and WDIA personality Rufus Thomas. Rufus brought in his daughter Carla, recent graduate of the station's Teentown Singers, and they became the first act to record at the new studio. Released as Satellite 102 in the summer of 1960, 'Cause I Love You by 'Carla and Rufus' was produced by Moman and featured Booker T (on baritone sax!), Marvell Thomas (Rufus' son) on piano, and Lewie Steinberg on bass. It was a big local hit, which perked up the ears of Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, who entered into an 'informal' distribution agreement with the company, re-releasing the 45 as Atco 6177.

As they renovated and got things set up, Estelle opened a record shop in what used to be the lobby. People came in off the street to see what was going on. People like a 16 year old Booker T. Jones, and WDIA personality Rufus Thomas. Rufus brought in his daughter Carla, recent graduate of the station's Teentown Singers, and they became the first act to record at the new studio. Released as Satellite 102 in the summer of 1960, 'Cause I Love You by 'Carla and Rufus' was produced by Moman and featured Booker T (on baritone sax!), Marvell Thomas (Rufus' son) on piano, and Lewie Steinberg on bass. It was a big local hit, which perked up the ears of Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, who entered into an 'informal' distribution agreement with the company, re-releasing the 45 as Atco 6177.The pot was growing.

Rufus Thomas had, unsuccessfully, tried to shop a demo tape of a song his daughter had written to Vee-Jay two years before, and brought it into the studio. Stewart loved it, and pulled out all the stops, actually booking Royal for the session which was to include (gulp) strings and everything. Unhappy with the results (Chips "hated it"), they re-cut it themselves with Moman producing. Although it took a while, Gee Whiz broke into the Billboard Hot 100 by late 1960, and Atlantic exercised their option, putting it out on their own imprint and promoting the hell out of it. It paid off, breaking into the top ten on both the R&B and Pop charts, and bringing in the label's first real dollars.

Rufus Thomas had, unsuccessfully, tried to shop a demo tape of a song his daughter had written to Vee-Jay two years before, and brought it into the studio. Stewart loved it, and pulled out all the stops, actually booking Royal for the session which was to include (gulp) strings and everything. Unhappy with the results (Chips "hated it"), they re-cut it themselves with Moman producing. Although it took a while, Gee Whiz broke into the Billboard Hot 100 by late 1960, and Atlantic exercised their option, putting it out on their own imprint and promoting the hell out of it. It paid off, breaking into the top ten on both the R&B and Pop charts, and bringing in the label's first real dollars.See that one, raise you another.

As we've discussed before, the Stax story is a convoluted and often controversial tale that's been comprehensively covered by Rob Bowman in his towering book, Soulsville U.S.A. You should read it. Essentially, at this point, all you need to know is that Estelle Axton didn't like Chips Moman, and the feeling was pretty much mutual. Axton was up there in the record shop, while Moman was basically running things back in the studio. Estelle's son Packy, who had become the sax player in Steve Cropper and Duck Dunn's band, The Royal Spades (due to the fact that his mother happened to own a record company) was scheduled for a session in early 1961.

As we've discussed before, the Stax story is a convoluted and often controversial tale that's been comprehensively covered by Rob Bowman in his towering book, Soulsville U.S.A. You should read it. Essentially, at this point, all you need to know is that Estelle Axton didn't like Chips Moman, and the feeling was pretty much mutual. Axton was up there in the record shop, while Moman was basically running things back in the studio. Estelle's son Packy, who had become the sax player in Steve Cropper and Duck Dunn's band, The Royal Spades (due to the fact that his mother happened to own a record company) was scheduled for a session in early 1961. For whatever reason, Chips, now almost 25, and a veteran of years out on the road, was not as impressed with this bunch of kids fresh out of high school as Estelle thought he should be. He was working on an instrumental based on some chord changes that he and keyboard player 'Smoochy' Smith had worked out, and recorded take after take of the song with different tempos and horn lines, trying to get the feel of it. He used Packy, Wayne Jackson, Cropper and other members of the Spades on the ongoing instrumental project (along with anyone else who happened to be around, like Gibert Caple, Floyd Newman and drummer Curtis Green). "It was a spontaneous effort by all of us," Wayne Jackson told Bowman, "We cut that record for a week, day in and day out, until we finally got a piece of tape that was from front to back okay."

For whatever reason, Chips, now almost 25, and a veteran of years out on the road, was not as impressed with this bunch of kids fresh out of high school as Estelle thought he should be. He was working on an instrumental based on some chord changes that he and keyboard player 'Smoochy' Smith had worked out, and recorded take after take of the song with different tempos and horn lines, trying to get the feel of it. He used Packy, Wayne Jackson, Cropper and other members of the Spades on the ongoing instrumental project (along with anyone else who happened to be around, like Gibert Caple, Floyd Newman and drummer Curtis Green). "It was a spontaneous effort by all of us," Wayne Jackson told Bowman, "We cut that record for a week, day in and day out, until we finally got a piece of tape that was from front to back okay." Estelle changed the name of the band to the Mar-Keys (as in Marquis) and leaked a copy of the tape to local station WLOK. The response was tremendous, but neither Chips nor her brother Jim, who had been traveling back and forth to Nashville putting the finishing touches on the LP that Atlantic wanted on Carla, seemed to care. She put her foot down, and demanded that they release it. When she sent Packy back to get the tape, it had somehow lost 30 seconds or so off the front end, and they had to scramble to find a segment of another take that matched it (while Estelle told all of this to Peter Guralnick in his interviews for Sweet Soul Music in rather histrionic tones, Moman called it a "simple splice"). In any event, Last Night (with the composers credit reading simply 'Mar-Keys' - even though the only members of the actual band to appear on the released version were Packy and Wayne Jackson) was a smash hit, selling over a million copies on its way to #3 on the pop charts that summer. When a west coast label named Satellite threatened to sue the company, Estelle and Jim decided to change its name to ST(ewart)AX(ton)...

Estelle changed the name of the band to the Mar-Keys (as in Marquis) and leaked a copy of the tape to local station WLOK. The response was tremendous, but neither Chips nor her brother Jim, who had been traveling back and forth to Nashville putting the finishing touches on the LP that Atlantic wanted on Carla, seemed to care. She put her foot down, and demanded that they release it. When she sent Packy back to get the tape, it had somehow lost 30 seconds or so off the front end, and they had to scramble to find a segment of another take that matched it (while Estelle told all of this to Peter Guralnick in his interviews for Sweet Soul Music in rather histrionic tones, Moman called it a "simple splice"). In any event, Last Night (with the composers credit reading simply 'Mar-Keys' - even though the only members of the actual band to appear on the released version were Packy and Wayne Jackson) was a smash hit, selling over a million copies on its way to #3 on the pop charts that summer. When a west coast label named Satellite threatened to sue the company, Estelle and Jim decided to change its name to ST(ewart)AX(ton)...Check.

Things were good. Moman's production style was establishing itself, and there was no shortage of musicians or ideas. His vision was paying off. Steve Cropper, who had been working in Estelle's record shop, would soon quit his own band (leaving it to Packy) and spend more time in the studio with Chips, learning the ropes. The first song he played guitar on as an actual session musician is one of my all-time favorites; I'm Going Home by Prince Conley. Produced by Moman, this awesome tune represents, in my opinion, the best of that early period, and a glimpse of what might have been.

Things were good. Moman's production style was establishing itself, and there was no shortage of musicians or ideas. His vision was paying off. Steve Cropper, who had been working in Estelle's record shop, would soon quit his own band (leaving it to Packy) and spend more time in the studio with Chips, learning the ropes. The first song he played guitar on as an actual session musician is one of my all-time favorites; I'm Going Home by Prince Conley. Produced by Moman, this awesome tune represents, in my opinion, the best of that early period, and a glimpse of what might have been. Sometime in 1961, Moman put together a working band that reflected the innovative and integrated nature of the studio at that time. He was living his dream, playing real R&B with a group that included Howard Grimes, Lewie Steinberg, Booker T. Jones and Marvell Thomas (as well as Gilbert Caple and Floyd Newman on the horns whenever they could make it). It was the first inter-racial act in Memphis. "Some of them good old boys didn't like it much, I guess," he said. He named the band 'The Triumphs'. That was the kind of car he had, a TR3. When Stax decided to create a subsidiary label, The Triumphs would have the first release, Volt 100. Today's greasy selection is the B side of that organ heavy groove, Burnt Biscuits (now up on The A Side). That's Chips playing the guitar on here. How cool is that?

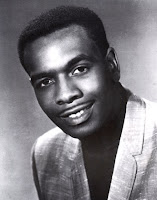

Sometime in 1961, Moman put together a working band that reflected the innovative and integrated nature of the studio at that time. He was living his dream, playing real R&B with a group that included Howard Grimes, Lewie Steinberg, Booker T. Jones and Marvell Thomas (as well as Gilbert Caple and Floyd Newman on the horns whenever they could make it). It was the first inter-racial act in Memphis. "Some of them good old boys didn't like it much, I guess," he said. He named the band 'The Triumphs'. That was the kind of car he had, a TR3. When Stax decided to create a subsidiary label, The Triumphs would have the first release, Volt 100. Today's greasy selection is the B side of that organ heavy groove, Burnt Biscuits (now up on The A Side). That's Chips playing the guitar on here. How cool is that? Moman had been trying to convince William Bell to step out from in front of the Del-Rios and record for Stax as a solo artist for over a year. By November of 1961 he was ready, and he brought a song he had written to the studio to record a demo on it. With Moman working the board, the incredible You Don't Miss Your Water turned out so good that they decided to release it just the way it was, setting the tone for virtually everything that was to follow at Stax...

Moman had been trying to convince William Bell to step out from in front of the Del-Rios and record for Stax as a solo artist for over a year. By November of 1961 he was ready, and he brought a song he had written to the studio to record a demo on it. With Moman working the board, the incredible You Don't Miss Your Water turned out so good that they decided to release it just the way it was, setting the tone for virtually everything that was to follow at Stax...Call.

What happened? Plainly put, I think once the money started rolling in, Estelle and Jim wanted Chips out. There was nothing on paper... Moman had been operating under the assumption that he owned 25% of the company, apparently because that's what Stewart had told him way back in the Brunswick days. Jim cut a session with Cropper while Moman wasn't around, and decided to release it, going so far as to call the group 'The M.G.'s', which was clearly derived from Chips' 'Triumphs' idea. It hit big... really big. It was the summer of 1962. There was an argument. Wayne Jackson (who 'still had pimples') heard it. Stewart told Moman; "I f#*ked you, and if you can prove it, fine, and if you can't... I'm the bookkeeper, and I've got the money!"

What happened? Plainly put, I think once the money started rolling in, Estelle and Jim wanted Chips out. There was nothing on paper... Moman had been operating under the assumption that he owned 25% of the company, apparently because that's what Stewart had told him way back in the Brunswick days. Jim cut a session with Cropper while Moman wasn't around, and decided to release it, going so far as to call the group 'The M.G.'s', which was clearly derived from Chips' 'Triumphs' idea. It hit big... really big. It was the summer of 1962. There was an argument. Wayne Jackson (who 'still had pimples') heard it. Stewart told Moman; "I f#*ked you, and if you can prove it, fine, and if you can't... I'm the bookkeeper, and I've got the money!""Well F#*k You!" Chips said, "If you need it that bad, keep it!" and he walked out the door, never to return.

Fold.

... continued in Part Two

3 Comments:

I enjoyed reading some of Chip Moman's history. I am kind of related to him by marriage. I have met him a few times and really enjoyed our conversations. 2 years ago I read him one of my poems I wrote for kids of all ages. He asked me to send him a copy and any others, but I am not sure how to get them to him. My email is mimisstories@live.net. thanx for your passing this on. Mary Scott.

ENJOYED THE MOMAN BIO. IT HAS BEEN ABOUT 53 YEARS OR SO BUT HE WAS MY FIRST TRUE LOVE WHEN I WAS A TEEN BACK IN LAGRANGE. GREAT TO SEE HOW FAR HE HAS COME. LAST TIME I SAW HIM I THINK I WAS HOME ON NAVY LEAVE. RE: NICKNAME "CHIPS" ASK HOW HE REALLY GOT THE NAME. ALSO WAYNE IF YOU HAPPEN TO READ THIS HI FROM MFD.

Mr Moman I truly am sorry that you were cheated. It's heart breaking to hear. My Father Marty Simon is being cheated of even the memory of him.

Post a Comment

<< Home