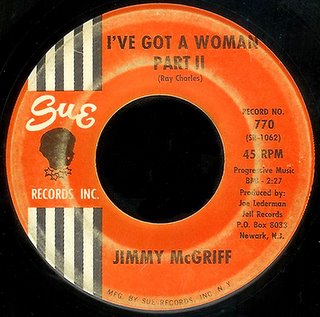

Jimmy McGriff - I've Got A Woman Pt. II (SUE 770)

I've Got A Woman Pt. II

Now that I can't turn on my radio without hearing Kanye West's hatchet job of Jamie Foxx's imitation of Brother Ray's Song of Songs, I figured it was time to testify!

Ray Charles' first records, on the Swingtime label, were west coast styled smooth R&B numbers that leaned heavily on the influence of Nat Cole and Charles Brown. When he signed with Atlantic Records in 1952, he began to find his own voice. He took up residence at the Foster Hotel in New Orleans the following year, and began sitting in with as many of the "local cats" as he could down at The Dew Drop Inn.

Ray Charles' first records, on the Swingtime label, were west coast styled smooth R&B numbers that leaned heavily on the influence of Nat Cole and Charles Brown. When he signed with Atlantic Records in 1952, he began to find his own voice. He took up residence at the Foster Hotel in New Orleans the following year, and began sitting in with as many of the "local cats" as he could down at The Dew Drop Inn.Eddie "Guitar Slim" Jones asked him if he'd like to play piano behind him on a "record date" about this time, and Charles jumped at the chance. He ended up more or less producing the session with Lloyd Lambert's band down at Cosimo's studio. When Specialty released The Things That I Used To Do, it became the biggest R&B hit of 1954, spending 21 weeks on the charts, with six weeks at number one. This pretty much convinced Ray that, if he wanted his own sound, he needed to form his own band. He was able to talk Atlantic into it by agreeing to back Ruth Brown as well, and set out for Texas to put it all together.

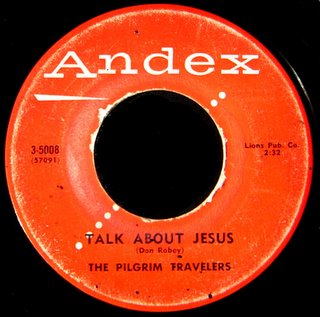

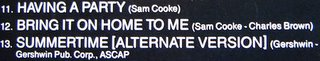

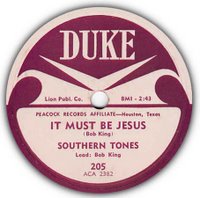

A record that was receiving almost as much airplay as Guitar Slim's that summer was It Must Be Jesus by The Southern Tones. There were probably more Gospel stations than R&B ones at that time in the South, and the music was just everywhere. It was on a tour with Ruth Brown that Ray and his trumpet player Renald Richard heard the song on the car radio. They began "messin' around" with it and, by the next day, Richard had come up with some new lyrics. Ray called Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler at Atlantic and asked them to come down to Atlanta to hear him and his new band. Wexler reports that he was "stunned" by the quality of their new material, and how tight the band was. They booked time at local radio station WGST's studio and recorded four songs under "primitive" conditions.

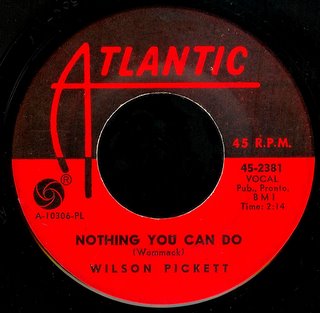

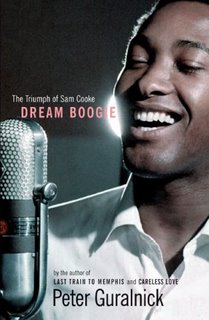

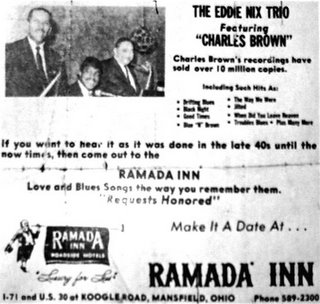

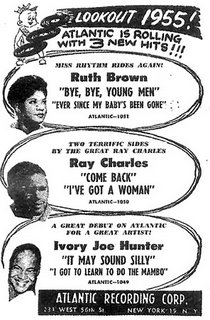

A record that was receiving almost as much airplay as Guitar Slim's that summer was It Must Be Jesus by The Southern Tones. There were probably more Gospel stations than R&B ones at that time in the South, and the music was just everywhere. It was on a tour with Ruth Brown that Ray and his trumpet player Renald Richard heard the song on the car radio. They began "messin' around" with it and, by the next day, Richard had come up with some new lyrics. Ray called Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler at Atlantic and asked them to come down to Atlanta to hear him and his new band. Wexler reports that he was "stunned" by the quality of their new material, and how tight the band was. They booked time at local radio station WGST's studio and recorded four songs under "primitive" conditions. When Atlantic released I've Got A Woman in January of 1955, they weren't quite sure how it would go over (if you look at the trade magazine ad at left, it appears that it was originally viewed as a B side!). Well, in the words of Peter Guralnick, it "set the music industry on it's head", went straight to number one R&B, and stayed there. The record was denounced from many a Southern pulpit as "the devil's music", and blues performers like Big Bill Broonzy looked on it as "mixing the sacred with the profane". All of this publicity, I'm sure, was music to the ears of Ray and Atlantic, and only served to make it an even bigger hit. It is commonly referred to today as "the first soul song".

When Atlantic released I've Got A Woman in January of 1955, they weren't quite sure how it would go over (if you look at the trade magazine ad at left, it appears that it was originally viewed as a B side!). Well, in the words of Peter Guralnick, it "set the music industry on it's head", went straight to number one R&B, and stayed there. The record was denounced from many a Southern pulpit as "the devil's music", and blues performers like Big Bill Broonzy looked on it as "mixing the sacred with the profane". All of this publicity, I'm sure, was music to the ears of Ray and Atlantic, and only served to make it an even bigger hit. It is commonly referred to today as "the first soul song".Now, I had always heard all that about Ray "bringing church" into the music and all, but it wasn't until I started looking into things a little further that I realized what all the fuss was about... he had taken a current Gospel hit (one that everybody in his mostly black, mostly southern audience was likely to know) and put new words to it - words about his baby bringin' him lovin' when he's in need... my, my! It is said (although I haven't unearthed a copy for myself yet... ) that it is literally a note for note thing.

What a trip...

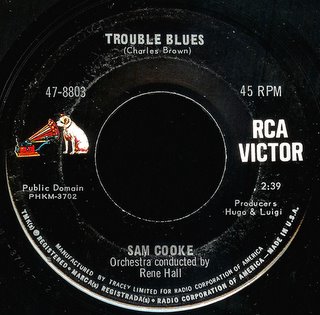

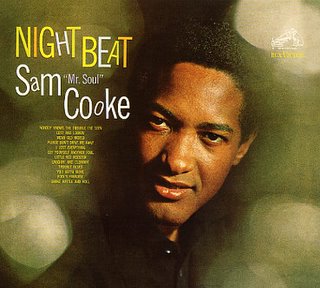

Bob King, the guy who wrote the original tune for The Southern Tones, was a blues influenced guitarist who was a big fan of North Carolina's Blind Boy Fuller. He joined Sam Cooke and The Soul Stirrers as their first guitar player in the summer of 1955. Less than a year later he would die of kidney failure.

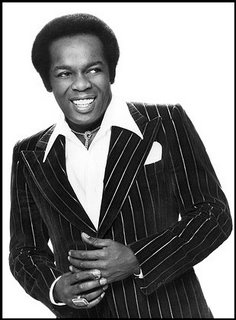

Meanwhile, young James McGriff was serving his time in Korea as an MP. Upon his return home to Philadelphia, he got a job in the police force. The music was "in him", however, and he began moonlighting gigs playing the bass behind artists like Big Maybelle at the famous Pep's Showboat on the South Side. He had always dug the organ, though, and when he heard Richard "Groove" Holmes play at his sister's wedding, he was hooked. He quit the cops and began concentrating on the Hammond, actually going to Julliard while continuing to study with Holmes as well as with Jimmy Smith and Milt Buckner.

Jimmy was playing in a small club in Trenton, New Jersey when his arrangement of I've Got A Woman caught the attention of Joe Lederman, who owned a small label called Jell Records. When his recording of it began to make some noise locally, it was picked up by Juggy Murray's Sue label for national distribution. It was a huge hit in 1962, breaking into the top 5 R&B as well as landing at #20 Pop, proving once again the power of this incredible song... by the time we get to Part II over here on the B side, Jimmy and his combo (featuring Morris Dow on the guitar and Jackie Mills on the drums) are just wreckin' the joint, y'all!

Jimmy was playing in a small club in Trenton, New Jersey when his arrangement of I've Got A Woman caught the attention of Joe Lederman, who owned a small label called Jell Records. When his recording of it began to make some noise locally, it was picked up by Juggy Murray's Sue label for national distribution. It was a huge hit in 1962, breaking into the top 5 R&B as well as landing at #20 Pop, proving once again the power of this incredible song... by the time we get to Part II over here on the B side, Jimmy and his combo (featuring Morris Dow on the guitar and Jackie Mills on the drums) are just wreckin' the joint, y'all! McGriff would go on to become one of the giants of the genre-busting funky organ, recording everything from acid jazz to straight ahead gospel, soul, and blues.

McGriff would go on to become one of the giants of the genre-busting funky organ, recording everything from acid jazz to straight ahead gospel, soul, and blues.His 1969 album The Worm would crack the R&B top ten, and pave the way for his 70's classics like Groove Grease and Soul Sugar. He has recorded over 100 albums, collaborating with everybody from Junior Parker to Hank Crawford and Dr. Lonnie Smith.

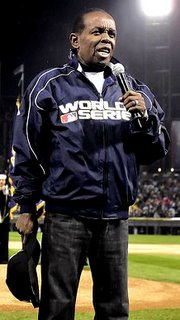

Although he has slowed down considerably, Jimmy still performs today and is an absolute master of that Philadelphia organ groove thang that we all love so well.

Although he has slowed down considerably, Jimmy still performs today and is an absolute master of that Philadelphia organ groove thang that we all love so well.I've Got A Woman has been covered countless other times (remember the sweet treatment Al Kooper gave it on Easy Does It in 1970?), and is a song that may well live forever.

So, when all is said and done, what do I think of #1 R&B hit Gold Digger? I'll be honest with you, I think it sucks... but I will say this; my two teenaged nephews were over here a couple of weeks ago, and they copied all the Ray Charles I have onto their iPods...

It's all good, I guess.

__________________________________________________________

UPDATE 3/10/06:

As you may know already, I had finally located a copy of the original Southern Tones version of "It Must Be Jesus" just before we went on vacation. Like I said, maybe Gold Digger is just Ray's cosmic justice...

As you may know already, I had finally located a copy of the original Southern Tones version of "It Must Be Jesus" just before we went on vacation. Like I said, maybe Gold Digger is just Ray's cosmic justice...It Must Be Jesus