Just To Satisfy You

Just To Satisfy You

PART FOUR

After closing down American; "...Moman and the band (with the exception of

Bobby Wood and

Gene Chrisman) moved to Atlanta... 'We built a studio in an industrial park,' remembers

Reggie Young, 'but there was nothing going on in Atlanta. we just sat around looking at each other...'" After about six months of this, Chips sold the studio to

Ilene Berns (who had relocated her husband's

BANG label down there after he died), and 'quit the business cold'. What was left of the 827 Thomas Street Band (along with

Sam Hutchins, who had made the trip to Georgia with them as well) had to fend for themselves.

In another great line from the excellent

Memphis Magazine article by

Eddie Hankins quoted above,

Mike Leech said "Reggie and I were driving through Nashville on our way back to Memphis, and we stopped in to make a couple of phone calls, and got booked on twenty sessions..." One of those sessions was for

Dobie Gray's top five Pop smash,

Drift Away. Reggie Young's shimmering guitar on that record insured him plenty of work in 'Music City' from that moment on... so much work that he eventually decided to charge 'double scale' in an effort to slow things down (it didn't work, they hired him anyway!).

Maybe Moman was just 'playing possum' again... I don't know. In any event, he couldn't stay away for long. In 1975,

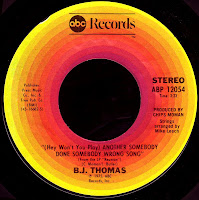

B.J. Thomas, who had cut his biggest Scepter hits at American, had just signed with ABC. Looking to rekindle the magic, they hired Chips and the rest of the American crew to produce an album titled, aptly enough,

Reunion. The first single released from that album would become an absolute phenomenon, going right to number one on both the Pop and Country charts.

(Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song was written for the album by Moman and former Gentry

Larry Butler (who had forged his own career as a Nashville producer by then), and proved to the industry that Chips still had it, earning him the Grammy for Country Song of the Year.

Waylon Jennings

Waylon Jennings had come up playing road gigs with

Buddy Holly, who would produce his first single in 1958. In February of 1959, after he gave up his seat on that ill-fated plane ride to the

Big Bopper, he was pretty much devastated when it all came crashing down. It took him a few years to regroup, but the music was in his blood, and he made a name for himself with his guitar-driven band

The Waylors out in Phoenix, Arizona. After a few local singles, he was picked up by A&M out on the west coast, but nothing much happened. It was Country star

Bobby Bare that suggested he move to Nashville, and got him hooked up with

Chet Atkins.

Jennings shared an apartment with

Johnny Cash at this point, who was hitting the top ten on the Country charts on a regular basis. Atkins' production of Waylon propelled him into the charts as well and he was soon hitting the top ten himself. By the end of the decade, Waylon had grown unhappy with the 'A Team' sound that the suits in Nashville were pushing on him, and demanded more creative freedom. Along with his wife

Jessi Colter, and like-minded souls like

Willie Nelson, he began creating what would become known as the 'outlaw movement' in Country music, which would take it's name from Wayon's 1972 album

Ladies Love Outlaws.

By 1976, the movement was in full swing, and RCA released a compilation album called

Wanted: The Outlaws, which featured Waylon, Willie, Jessi, and

Tompall Glaser. An absolute smash, that record would become the first Country LP to sell a million copies, going #1 Country, and #10 pop.

Good Hearted Woman, a live duet with Willie Nelson, was pulled as a single, and went straight to the top of the Country charts. He would also make the number two spot with a cover of

Suspicious Minds, written, of course, by

Mark James, formerly of AGP.

Chips, meanwhile, had built his own Nashville studio 'a respectful distance from Music Row'. Empowered by the Grammy he received the year before, he was now seen as a major force in Country music. That, coupled with his own well-known 'outlaw' sensibilities, put him in the right place at the right time to work with Waylon and Willie (and the boys). He and

Bobby Emmons got together and wrote what would become the signature song of Jennings' later career,

Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love), an absolute monster hit that would spend six weeks at the top of the Country charts in 1977.

Moman produced the album it was taken from,

Ol' Waylon, which remains one of Jennings' biggest sellers. Chips had known Willie Nelson from his days of doing demo work for

Buddy Killen's

Tree Publishing Company, when Willie was a struggling songwriter, and he was happy to add his voice to the album, which only added to the 'outlaw' image that was all the rage back then.

RCA would release an album entitled

Waylon & Willie the following year, which capitalized on the success of Luckenback, and generated four top five Country hits, the most famous being, of course,

Mammas Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Cowboys. Although not produced by Moman, he and Emmons had written another of those hit singles,

The Wurlitzer Prize (I Don't Want to Get Over You).

Moman's studio was again in demand, and he recorded some classic albums there, like 'King of the Honky Tonks'

Gary Stewart's

Cactus And A Rose, which featured

Bonnie Bramlett and members of

The Allman Brothers, further blurring the line between 'Country' and 'Southern Rock' in 1980.

In 1981, Waylon was back in the studio with Chips working on an album called

Black On Black. A radical departure from what Jennings had been doing recently (like the straight ahead Country of the

Theme from The Dukes Of Hazzard), Moman built a fuller sound around Bobby Emmons and the rest of his 'Memphis Boys' along with Jessi Colter's background vocals.

He also brought Willie Nelson back in to sing with him on one cut, today's cool selection (the B side of one of those 'double A-sided' promo 45s - hey, I'll take it!). A remake of a song Jennings had hit with way back in 1969, RCA released it as a 'Waylon & Willie' single and it took off, rising to #2 Country in early 1982.

Chips then turned his attention to Willie, producing one of his biggest albums ever,

Always On My Mind. The title track had been written by former Press Co. writers Mark James and

John Christopher (along with

Wayne Carson) and had been a top twenty Country hit for Elvis in 1972, bypassing

Brenda Lee's original version from the same year. As we've said before, this was where Moman's genius as a producer lie, in matching the singer with the song. Nelson took it into the top five on both the Pop and Country charts, and won the Grammy for his vocal performance, in addition to the song being picked as 'song of the year' for 1982. Not bad.

Before the year was out, Chips also produced

WWII, which brought Waylon & Willie back together again, and made #3 on Billboard's Country LP chart. A duet on

Sittin' On The Dock Of The Bay would make it to #13 Country.

In 1983, Chips paired Nelson with another of Country's notorious 'bad boys',

Merle Haggard. The atmospheric

Pancho and Lefty cruised to the top of both the singles and album charts that year, and further solidified Moman's status as one of Nashville's hottest producers.

Willie was just cookin' on all burners at this point, due in large part to his partnership with Moman. His 1984 album

City Of New Orleans continued in the same vein, with the album topping the Country LP chart, and the title track going to #1 as well.

When The Man In Black came knockin', Chips was ready.

The idea of forming a Country 'super-group' grew out of sessions for an upcoming

Johnny Cash album at Moman's studio. As old friends

Kris Kristofferson (who had written one of Johnny's biggest hits,

Sunday Morning Comin' Down), Waylon and Willie came around, they started hanging out and singing together. One of the songs Cash was working on was

Jimmy Webb's

Highwayman, and they each ended up taking a verse. Released as a single in 1985, it predictably soared to the top.

After a follow-up single broke into the top twenty later that year, the Moman produced Highwayman

album was released, to much critical acclaim. Interestingly, the group wasn't known as 'The Highwaymen' until much later, but as 'Nelson, Jennings, Cash, Kristofferson'. Chips, once an outsider in Music City, had come in and done things his way, producing the best and brightest in Country music along the way, as evidenced by this incredible album.

Out of those same sessions came

Heroes, an album by Cash and Waylon that was released the following year. The title track was another of those Moman/Emmons compositions, and

Even Cowgirls Get The Blues would break into the top twenty. No matter what you might think of the music, the fact remains that Chips Moman at this point in time was considered a guaranteed 'hit-maker', at the top of his game.

As outlined by

James L. Dickerson in his great book

Goin' Back To Memphis, all that was about to change. He interviewed Chips right around this time, and asked him if he ever regretted leaving Memphis. "Every record I've cut since then, I've said 'Yeah, I cut it in Nashville, but my music is still in Memphis,' because that's where I got it. That's where I learned it, that's where I felt it." he told him. Partially as a result of that interview, Moman (who sports an ancient 'jailhouse tattoo' that reads 'Memphis' on his arm) was lured back to the city he loved by the promise of a suite in the Peabody Hotel and a handshake deal with then mayor

Dick Hackett that promised him a city-owned building (for one dollar) in which he could build a studio. The idea was to somehow rejuvenate the city's all but defunct music scene by attracting one of its prime movers and shakers back to town. Moman jumped at the chance, and wholeheartedly set about trying to make it happen.

He came up with the idea of another 'super-group', this one composed of four legends who had gotten their start at the Sun studio in 1955;

Jerry Lee Lewis,

Carl Perkins,

Roy Orbison and Johnny Cash (the fact that Cash was at home both here and in The Highwaymen speaks volumes about what a star he really was). He got

Sam Phillips involved and, informally dubbing the group 'The Four Horsemen', arranged to record the album at Sun in September of 1985.

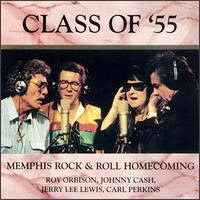

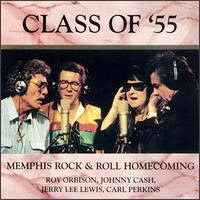

Actually finishing the tracks at American, which hadn't been used as a studio since he left 13 years before, Chips put together an album called

The Class of '55, that he was sure was going to be a big hit. After all the major record companies passed on it, he decided to once again form his own label, America, to release the album. Putting together a group of local investors to back the company, he secured distribution with Polygram in Nashville. Although it sold well locally, there didn't seem to be a market for it outside of Memphis, and the album died a quiet death. Incredibly, the companion disc,

Interviews From The Class of '55 Recording Sessions, won the Grammy in 1986 for Best Spoken Word or Non-Musical Recording. Go figure.

Moman held the City Government to its word, and leased an empty firehouse from them for a dollar a year, turning it into Three Alarm Studios. He wanted to cut a hit on a national act to start things off right, and turned to old friend (and former member of the American Group)

Bobby Womack. "I couldn't think of anyone I would rather try to get a hit with than Bobby," Chips told Dickerson, "He's got a distinct style. He's a great singer, writer, and guitar player. That's about all you could ask for." While all of that is certainly true, and

Womagic received excellent reviews when it was released in late 1986, it didn't sell. The investors in America Records were getting nervous.

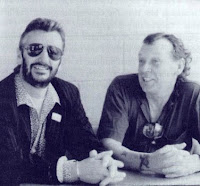

What better way to calm everybody down than by recording a sure thing? How about a Beatle?

Ringo came to Memphis in early 1987 to cut an album at Three Alarm with Chips and the full 827 Thomas Street Band. Things were looking good. After laying down sixteen solid tracks, Starr threw a party on a riverboat on the mighty Mississippi, and everybody was happy. For some insane reason, however, Ringo ended up suing Chips in Federal Court to stop him from releasing the album, which he said was recorded while he was 'on drugs and alcohol' (even though nobody in Memphis remembers seeing him getting high) and that he considered it 'an embarrassment'. The courts 'permanently barred' the album from being released, but ordered Ringo to pay Three Alarm for the studio time. By then it was a case of too little too late. The whole 'rejuvenation' thing was not happening, and seemingly all of Memphis blamed Chips. According to Dickerson, he had 'made one deal too many', and owed people money all over town.

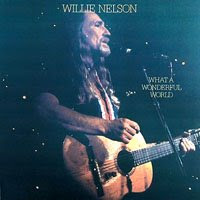

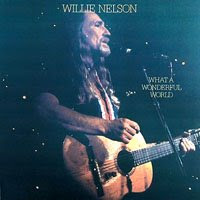

In 1988, the increasingly paranoid Moman produced an album of standards on old pal Willie Nelson at the home studio he had built for him in Texas. Mixing the album at Three Alarm, songs like

What A Wonderful World and

Ac-cent-tchu-ate The Positive contrasted bleakly with how he felt. Once again, his love affair with Memphis had gone up in smoke. The dream was at an end, and he knew it. By late 1989, Chips had sold off his studio to a 'used car dealer', and had lost his house as well. He was forced to declare bankruptcy and, after spending a weekend in jail on a trumped up 'contempt of court' charge, he left Memphis for good in 1990, shaking the dust from his boots. Ironically, that would also be the year that he was inducted into the

Georgia Music Hall of Fame.

Back in Nashville, friends gathered around him, and he began work on the Highwayman 2 project. The album, although not received that well by the critics, went to #4 on the Country LP charts and earned a Grammy nomination, which is actually pretty amazing considering Chips state of mind at the time. He found himself adrift once again, and by the end of the decade he had returned home to Georgia, building a studio on the farm he had bought just outside of West Point, less than twenty miles away from the town he grew up in.

Never one to be kept down, Chips had started up his own website,

chipsmoman.com by early 2001. It was a warm and friendly place, complete with pictures of 'Old McMoman's Farm', and a monthly newsletter that kept you up to date with what was happening with the extended family (and the dogs). He had built a special climate controlled building to house the thousands of hours of unreleased master tapes he had accumulated over the years, and was methodically going through them, with plans of releasing them in the near future.

The Memphis Boys

The Memphis Boys were regular visitors and, in between poker games, Chips was recording new material on

Billy Lee Riley and

Billy Joe Royal (with his son Casey working the board) to complement some of the great original material he had found in 'the vault'. Starting up yet another record label (chipsmoman.com Records), he released an album on Royal called

Now and Then, Then and Now. There were plans for an internet radio station, and even an autobiography.

Dan Penn came to visit. Things were good. Inexplicably, the site went off-line sometime in 2003, and is no longer available.

Papa Don Schroeder

Papa Don Schroeder told me that he was driving through Georgia with the bride last year in his motor home, and pulled up outside the Cracker Barrel in La Grange. He called Chips' cell phone, figuring as long as he was in town he'd stop in and see him. Chips picked up the phone and told him to just come on inside, that he was already in there ordering lunch! Imagine? Don said it was absolutely great to see his old running partner, and that they "always had fun together."

As you may know, The Memphis Boys were inducted into The Nashville

Musicians Hall Of Fame last November. I think that's great, but it kind of seems like putting the cart before the horse, or something. As Bobby Emmons has been quoted as saying, "We all just worked as a team, with Chips as the leader." He belongs in there too.

I really don't think you can say enough about the artistry and scope of Chips Moman's musical accomplishments over the course of a career that has now spanned over fifty years. He belongs in the

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and the

Country Music Hall of Fame as well, to say the very least.

It would be hard to imagine American music without him.

Thanks, Chips.

...Epilogue

The Time We Have

The Time We Have This sweet selection we have here today was the flip of Into Something (Can't Shake Loose), which climbed to #43 R&B in the fall of 1977. Written by Willie Mitchell and Earl Randle, it offers us a window into O.V.'s mellow side, and shows just how deep he managed to remain through it all. ABC had chosen not to renew his Back Beat contract in 1976, and Wright signed with Hi, which had become a subsidiary of Cream Records by then. The three LPs he recorded for Hi with Willie in Memphis in the late seventies are often overlooked in favor of those untouchable Back Beat singles from a few years before. While I can certainly relate to that, I think it's worth taking in the whole picture, and checking out the great music Mitchell and Wright continued to create at Royal, even as all that disco fever raged on outside the door.

This sweet selection we have here today was the flip of Into Something (Can't Shake Loose), which climbed to #43 R&B in the fall of 1977. Written by Willie Mitchell and Earl Randle, it offers us a window into O.V.'s mellow side, and shows just how deep he managed to remain through it all. ABC had chosen not to renew his Back Beat contract in 1976, and Wright signed with Hi, which had become a subsidiary of Cream Records by then. The three LPs he recorded for Hi with Willie in Memphis in the late seventies are often overlooked in favor of those untouchable Back Beat singles from a few years before. While I can certainly relate to that, I think it's worth taking in the whole picture, and checking out the great music Mitchell and Wright continued to create at Royal, even as all that disco fever raged on outside the door.