James Carr - Forgetting You (Goldwax 311)

Forgetting You

Now let's move on to that other vocalist that knocked on Quinton Claunch's door that fateful night in 1964... a man some say was the best soul singer of them all, James Carr.

Carr's story, as a subplot of the whole Goldwax saga, remains one that captures the imagination. It's a tale of madness and 'personal demons', of a twisted and tortured interior struggle that would plague James his entire life... a tale of how that chaos was redeemed in the timeless body of work that he created in just a few short years - a body of work that includes, in my opinion, the greatest song ever recorded.

Carr's story, as a subplot of the whole Goldwax saga, remains one that captures the imagination. It's a tale of madness and 'personal demons', of a twisted and tortured interior struggle that would plague James his entire life... a tale of how that chaos was redeemed in the timeless body of work that he created in just a few short years - a body of work that includes, in my opinion, the greatest song ever recorded.A simple man who, some say, never learned to read or write, Carr grew up in Memphis singing in local Gospel quartets like the Harmony Echoes. His first record for the label, You Don't Want Me (Goldwax 108), was pretty much a straight-ahead Blues number that was recorded around the same time as O.V.'s big single. The flip of that record, Only Fools Run Away, although kind of like an over-produced Arthur Alexander tune, gives a glimpse of the vocal power that was to come. Lover's Competition (Goldwax 112) would follow, and essentially mine the same syrupy territory without much luck.

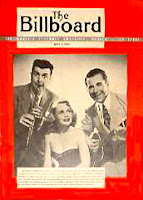

By 1965, things were really starting to happen down there in 'Soul City U.S.A.', and Goldwax found itself in the right place at the right time. Claunch's connections in the local music scene began to pay off, especially his friendship with former Sun pedal steel man turned engineer, Stan Kesler. Stan (pictured here with Claunch and Doc Russell) worked the board over at the Sam Phillips Recording Service, the state-of-the-art studio Phillips had set up in 1959.

By 1965, things were really starting to happen down there in 'Soul City U.S.A.', and Goldwax found itself in the right place at the right time. Claunch's connections in the local music scene began to pay off, especially his friendship with former Sun pedal steel man turned engineer, Stan Kesler. Stan (pictured here with Claunch and Doc Russell) worked the board over at the Sam Phillips Recording Service, the state-of-the-art studio Phillips had set up in 1959. It was Kesler, they say, that first put together the incredible rhythm section that would later become the 'house band' at Chips Moman's American Studio. Goldwax had no studio of their own, and so booked time wherever they could find it. Carr, as I understand it, was recorded primarily at Sam Phillips, using that core group of Reggie Young, Bobby Emmons, Gene Chrisman, Tommy Cogbill, Mike Leech, and Bobby Wood. Wherever it was that they were rolling the tape, things really began to come together for Carr and the label. Goldwax 119 paired the upbeat Talk Talk with the great She's Better Than You, a song written by a kid named O.B. McClinton.

It was Kesler, they say, that first put together the incredible rhythm section that would later become the 'house band' at Chips Moman's American Studio. Goldwax had no studio of their own, and so booked time wherever they could find it. Carr, as I understand it, was recorded primarily at Sam Phillips, using that core group of Reggie Young, Bobby Emmons, Gene Chrisman, Tommy Cogbill, Mike Leech, and Bobby Wood. Wherever it was that they were rolling the tape, things really began to come together for Carr and the label. Goldwax 119 paired the upbeat Talk Talk with the great She's Better Than You, a song written by a kid named O.B. McClinton.  McClinton had been with the label almost since its inception, and Goldwax had released his own version of the song the year before. Like the personal embodiment of the company's sound, O.B. was a black man who wrote, and performed, Country music. He had been raised in Mississippi and, by his own recollection, had fallen in love with the sound of Hank Williams on the radio when he was a kid. Still a student at Rust College when fellow songwriter Earl Cage brought him to Claunch's attention, he would go on to write some of Carr's best material. McClinton, after recording for Stax subsidiary Enterprise in the early seventies, later became known as The Chocolate Cowboy, breaking down all the barriers as he appeared some fifteen times on the Billboard Country charts before his untimely death in 1987.

McClinton had been with the label almost since its inception, and Goldwax had released his own version of the song the year before. Like the personal embodiment of the company's sound, O.B. was a black man who wrote, and performed, Country music. He had been raised in Mississippi and, by his own recollection, had fallen in love with the sound of Hank Williams on the radio when he was a kid. Still a student at Rust College when fellow songwriter Earl Cage brought him to Claunch's attention, he would go on to write some of Carr's best material. McClinton, after recording for Stax subsidiary Enterprise in the early seventies, later became known as The Chocolate Cowboy, breaking down all the barriers as he appeared some fifteen times on the Billboard Country charts before his untimely death in 1987. It was McClinton who delivered James' first hit, the great You've Got My Mind Messed Up, which would spend two months on the charts, breaking into the R&B top ten in the spring of 1966. The follow-up, Love Attack (penned by Claunch himself, who had become quite the songwriter), hit #21 that summer, and James was on a roll. This was also around the time that Claunch signed on with Larry Utall, whose New York based Bell Records now became the Goldwax distributor.

It was McClinton who delivered James' first hit, the great You've Got My Mind Messed Up, which would spend two months on the charts, breaking into the R&B top ten in the spring of 1966. The follow-up, Love Attack (penned by Claunch himself, who had become quite the songwriter), hit #21 that summer, and James was on a roll. This was also around the time that Claunch signed on with Larry Utall, whose New York based Bell Records now became the Goldwax distributor.  As I'm sure you know, Peter Guralnick spoke about all of this at length in his ground-breaking work, Sweet Soul Music. Particular attention was paid to the relationship between Roosevelt Jamison and our man James. Jamison had become his confidant, mentor and manager, and saw him as "pure clay to be molded." Once Utall began moving some serious product on him, he convinced Goldwax to fire Jamison, and place Carr with Walden Booking, the mega-agency created by Phil Walden that managed Otis Redding, and just about everybody else in those days. In the book, Jamison says "They didn't know how he actually felt... how hard it was coming from the bottom, from nothing to something so fast. It was like coming from four or five years old to twenty five all of a sudden... within six months he came tumbling all the way down." Be that as it may, it is precisely that period of turmoil that would produce his greatest work.

As I'm sure you know, Peter Guralnick spoke about all of this at length in his ground-breaking work, Sweet Soul Music. Particular attention was paid to the relationship between Roosevelt Jamison and our man James. Jamison had become his confidant, mentor and manager, and saw him as "pure clay to be molded." Once Utall began moving some serious product on him, he convinced Goldwax to fire Jamison, and place Carr with Walden Booking, the mega-agency created by Phil Walden that managed Otis Redding, and just about everybody else in those days. In the book, Jamison says "They didn't know how he actually felt... how hard it was coming from the bottom, from nothing to something so fast. It was like coming from four or five years old to twenty five all of a sudden... within six months he came tumbling all the way down." Be that as it may, it is precisely that period of turmoil that would produce his greatest work. Today's unbelievable selection was released as the flip of the upbeat mover, Pouring Water On A Drowning Man, which would cruise to #23 R&B in the fall of 1966. Written by McClinton, it's basically a Country record all the way... that is until the last thirty seconds or so, when the band (led by that incredible Reggie Young guitar*) shifts things down to a minor key, then just builds and builds... with those trademark Memphis Horns and James' positively primal howls and shrieks. Whoa!! Goose Bumps, man. This is the pure essence of soul music right here, folks, and when you take it in context as the B side of the single before this next one, it seems even better.

Today's unbelievable selection was released as the flip of the upbeat mover, Pouring Water On A Drowning Man, which would cruise to #23 R&B in the fall of 1966. Written by McClinton, it's basically a Country record all the way... that is until the last thirty seconds or so, when the band (led by that incredible Reggie Young guitar*) shifts things down to a minor key, then just builds and builds... with those trademark Memphis Horns and James' positively primal howls and shrieks. Whoa!! Goose Bumps, man. This is the pure essence of soul music right here, folks, and when you take it in context as the B side of the single before this next one, it seems even better. What more can be said about Goldwax 317? What could I possibly add to the discussion of this elemental and pure work of art? Not much, I suppose, except to add my voice to those who consider The Dark End Of The Street the best record ever made. Born of a poker game at a Nashville disk jockey convention in 1966 (the same convention, by the way, that got Huey Meaux in all that trouble for providing the 'entertainment'), and written by an unholy alliance of two white guys who were ultimately too much alike to be together for very long, it doesn't seem possible that it was ever written at all. When the board at American blew up the day of the scheduled session, they had to move it across town to Royal at the last minute. The stars were aligning...

What more can be said about Goldwax 317? What could I possibly add to the discussion of this elemental and pure work of art? Not much, I suppose, except to add my voice to those who consider The Dark End Of The Street the best record ever made. Born of a poker game at a Nashville disk jockey convention in 1966 (the same convention, by the way, that got Huey Meaux in all that trouble for providing the 'entertainment'), and written by an unholy alliance of two white guys who were ultimately too much alike to be together for very long, it doesn't seem possible that it was ever written at all. When the board at American blew up the day of the scheduled session, they had to move it across town to Royal at the last minute. The stars were aligning...What is it that makes this song so great? To tell you the truth, I don't know, but it still moves me every single time I hear it. Perhaps it's the transparency, the palpability of Carr's unique voice... the unguarded window into his soul. As Robert Gordon put it in his excellent article, James Carr: Way Out On A Voyage; "We are not sung to... the performance is not one we witness from the audience but one we feel through him. [Otis] Redding made a gift of his passion, something we could admire from a distance. Carr's passion is reciprocal..." Amen.

It would reach the R&B top ten in early 1967, and be included, along with most of his other singles, in Goldwax' first LP release later that year. It remains one of the most sought after slabs of vinyl out there. Although James would chart five more times for the label (most notably with O.B. McClinton's great composition A Man Needs A Woman, which would also become the title track for a follow-up LP in 1968), it was almost as if he had left it all out there... I mean, how do you follow perfection?

It would reach the R&B top ten in early 1967, and be included, along with most of his other singles, in Goldwax' first LP release later that year. It remains one of the most sought after slabs of vinyl out there. Although James would chart five more times for the label (most notably with O.B. McClinton's great composition A Man Needs A Woman, which would also become the title track for a follow-up LP in 1968), it was almost as if he had left it all out there... I mean, how do you follow perfection?He was a haunted man.

Stories abound about Carr's descent into a bi-polar depressive nightmare. About failed recording sessions and concert tours. About how, after Goldwax threw in the towel in 1969, and his lone Atlantic single died in 1970, he basically could not account for his whereabouts for the next ten years. Attempts were made to resurrect his career. Jamison himself took him to Japan in 1979, on a tour that was destined to fail.

Stories abound about Carr's descent into a bi-polar depressive nightmare. About failed recording sessions and concert tours. About how, after Goldwax threw in the towel in 1969, and his lone Atlantic single died in 1970, he basically could not account for his whereabouts for the next ten years. Attempts were made to resurrect his career. Jamison himself took him to Japan in 1979, on a tour that was destined to fail. A re-incorporated version of the Goldwax label would record an album on him in 1990 called Take Me To The Limit, and bring him back out on the road to promote it. This was when I saw James at Tramps in New York. The raw power of his voice was still intact. I was blown away.

A re-incorporated version of the Goldwax label would record an album on him in 1990 called Take Me To The Limit, and bring him back out on the road to promote it. This was when I saw James at Tramps in New York. The raw power of his voice was still intact. I was blown away.  At the time, though, I don't think I fully appreciated what I was witnessing... a show that Gordon called a "personal and professional triumph," I didn't know it would be one of his last. There is a chilling video of him at Porretta from around this same time on YouTube. Unreal.

At the time, though, I don't think I fully appreciated what I was witnessing... a show that Gordon called a "personal and professional triumph," I didn't know it would be one of his last. There is a chilling video of him at Porretta from around this same time on YouTube. Unreal.He would record one more album, Soul Survivor, for Soultrax in 1994.

James Carr spent the last few years of his life living at his sister's house in Memphis. After losing a lung to cancer, he died at a nursing home there in January of 2001. He was 58 years old.

That's the way love turned out for him.

*please see: https://soulsauce.me/2021/09/30/james-carr-forgetting-you/