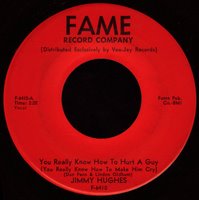

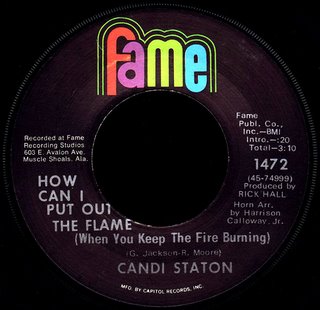

Candi Staton - How Can I Put Out The Flame (When You Keep The Fire Burning) (Fame 1472)

How Can I Put Out The Flame (When You Keep The Fire Burning)

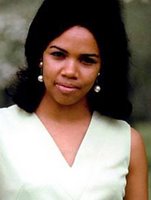

Canzetta Staton started out as a farm girl in northern Alabama. She knew she wanted to sing by the time she was about four years old, and the pastor of her church recognized her unique gift. Together with her sister Maggie and two other girls, they formed a group called the Four Golden Echoes that traveled with the pastor to churches all over the state. Increasing problems at home caused her parents split up in the early fifties, however, and her mother moved the family to Cleveland.

A devout Pentecostalist, mom sent the girls to a Christian Academy that was run by Bishop Mattie Lou Jewell in Nashville. Impressed by the girls' talent, the Bishop got them together with her grandaughter Naomi Harrison and formed the Jewell Gospel Trio in 1953. This adorable group of youngsters became extremely popular in the South, and it wasn't long before they were touring the state raising money for the Academy. As their fame spread, they added steel guitar and 'Hawaiian drums' and began traveling the 'Gospel Highway' in caravans along with groups like The Soul Stirrers, Pilgrim Travelers and The Staple Singers. It was Mavis Staples who began calling her 'Candy', telling her she was too sweet to have a name nobody could pronounce.

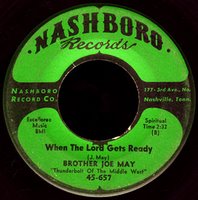

A devout Pentecostalist, mom sent the girls to a Christian Academy that was run by Bishop Mattie Lou Jewell in Nashville. Impressed by the girls' talent, the Bishop got them together with her grandaughter Naomi Harrison and formed the Jewell Gospel Trio in 1953. This adorable group of youngsters became extremely popular in the South, and it wasn't long before they were touring the state raising money for the Academy. As their fame spread, they added steel guitar and 'Hawaiian drums' and began traveling the 'Gospel Highway' in caravans along with groups like The Soul Stirrers, Pilgrim Travelers and The Staple Singers. It was Mavis Staples who began calling her 'Candy', telling her she was too sweet to have a name nobody could pronounce. The Trio's first sides were issued on Alladin, but it wasn't until they were signed to Nashboro in 1955 that they began to get noticed. It was Maggie who sang the lead on their biggest record, I Looked Down The Line And I Wondered, but Candy was out front for Jesus Is Listening and the wonderful Too Late. By 1960, the girls realized that they weren't being adequately compensated for their efforts, and left the Trio, and Bishop Jewell behind.

The Trio's first sides were issued on Alladin, but it wasn't until they were signed to Nashboro in 1955 that they began to get noticed. It was Maggie who sang the lead on their biggest record, I Looked Down The Line And I Wondered, but Candy was out front for Jesus Is Listening and the wonderful Too Late. By 1960, the girls realized that they weren't being adequately compensated for their efforts, and left the Trio, and Bishop Jewell behind.Maggie went off to college, but Candy headed back to her country roots in Alabama, finished high school, and married the son of a local minister. She settled in to a life of playing the church organ and singing in the choir of her father-in-laws strict fundamentalist congregation, while she raised her kids. Eventually she became fed up with the 'hypocrisy' she saw all around her, and was ready to move on. The last straw came when the pastor actually kicked her out of his church because she dared to have a television at home. At that point, she remembers thinking "...forget God, and forget everything associated with God."

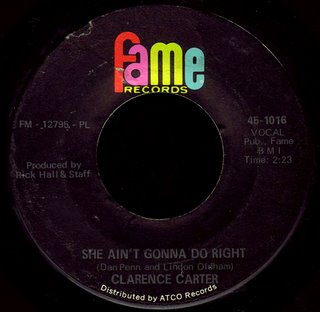

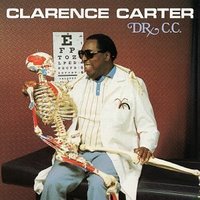

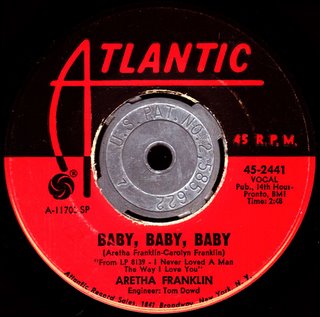

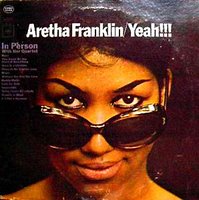

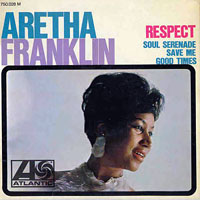

Candy's brother took her to a place called the 27/28 Club in Birmingham in 1968. He dared her to get up and sing at an 'open mike' night they were having. She got up there and sang the only secular song she knew, Do Right Woman-Do Right Man, the Penn-Moman classic she had learned from Aretha's smash album the year before. The owner of the club couldn't believe how great she was, and hired her on the spot. After Candy went home and learned a few more songs, she came back ready to perform, and learned she was opening for local legend Clarence Carter. Carter was blown away as well, and asked her to sing a few songs with his band. They began touring the chitlin' circuit together, and Staton learned her chops as an R&B singer on the road with him.

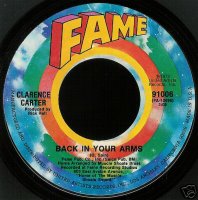

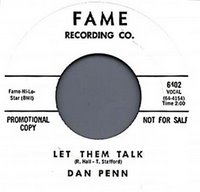

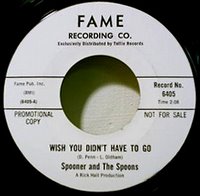

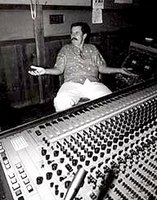

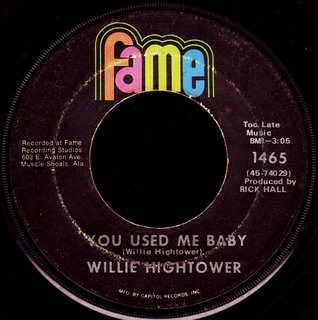

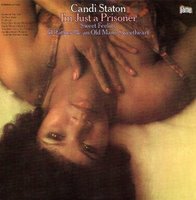

Candy's brother took her to a place called the 27/28 Club in Birmingham in 1968. He dared her to get up and sing at an 'open mike' night they were having. She got up there and sang the only secular song she knew, Do Right Woman-Do Right Man, the Penn-Moman classic she had learned from Aretha's smash album the year before. The owner of the club couldn't believe how great she was, and hired her on the spot. After Candy went home and learned a few more songs, she came back ready to perform, and learned she was opening for local legend Clarence Carter. Carter was blown away as well, and asked her to sing a few songs with his band. They began touring the chitlin' circuit together, and Staton learned her chops as an R&B singer on the road with him. When Clarence brought her to Muscle Shoals to meet Rick Hall, he just loved her and signed her to Fame right then and there. It was Rick who changed the 'Candy' to 'Candi' and promised to make her a star. Her first Fame sessions were held in September of 1968, and the resulting single I'd Rather Be An Old Man's Sweetheart (Than A Young Man's Fool) (co-written by Carter, Raymond Moore and new staff songwriter George Jackson) became a huge hit down South, spending ten weeks on the national R&B charts, and breaking into the top ten. Candi couldn't believe it, and recalls staying up all night and switching stations on the radio while they played her song all up and down the line. Hall had kept his promise, and his new star came to be known as the 'Sweetheart of Soul'. The out-of-print Fame LP built around her first four chart hits for the label, I'm Just A Prisoner, is universally acknowledged as one of the greatest southern soul albums ever made (come on, EMI).

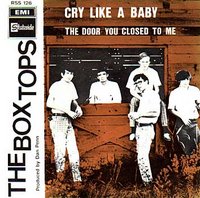

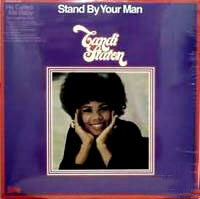

When Clarence brought her to Muscle Shoals to meet Rick Hall, he just loved her and signed her to Fame right then and there. It was Rick who changed the 'Candy' to 'Candi' and promised to make her a star. Her first Fame sessions were held in September of 1968, and the resulting single I'd Rather Be An Old Man's Sweetheart (Than A Young Man's Fool) (co-written by Carter, Raymond Moore and new staff songwriter George Jackson) became a huge hit down South, spending ten weeks on the national R&B charts, and breaking into the top ten. Candi couldn't believe it, and recalls staying up all night and switching stations on the radio while they played her song all up and down the line. Hall had kept his promise, and his new star came to be known as the 'Sweetheart of Soul'. The out-of-print Fame LP built around her first four chart hits for the label, I'm Just A Prisoner, is universally acknowledged as one of the greatest southern soul albums ever made (come on, EMI). Her biggest hit for the label was a Clarence Carter arrangement of Tammy Wynette's country anthem Stand By Your Man. The song was actually co-written by Tammy with Billy Sherrill who, you may recall, had been a member of the Fairlanes and a co-founder of Florence Alabama Music Enterprises with Tom Stafford and Rick Hall. As good an example of 'country soul' as you're likely to find, it roared to #4 R&B (#24 pop) in the summer of 1970, spending over 4 months on the charts. Today's selection is the B side of that single (as well as being a track on the accompanying Fame LP), and illustrates just how good Rick Hall's label remained after everyone left. With George Jackson and Raymond Moore's incredible songwriting and Harrison Calloway, Junior Lowe and the rest of the Fame Gang's tight playing on here, I think this record stands up with the best of the 'second rhythm section' stuff. I just love it.

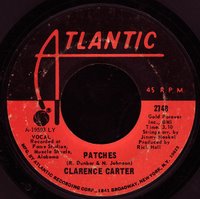

Her biggest hit for the label was a Clarence Carter arrangement of Tammy Wynette's country anthem Stand By Your Man. The song was actually co-written by Tammy with Billy Sherrill who, you may recall, had been a member of the Fairlanes and a co-founder of Florence Alabama Music Enterprises with Tom Stafford and Rick Hall. As good an example of 'country soul' as you're likely to find, it roared to #4 R&B (#24 pop) in the summer of 1970, spending over 4 months on the charts. Today's selection is the B side of that single (as well as being a track on the accompanying Fame LP), and illustrates just how good Rick Hall's label remained after everyone left. With George Jackson and Raymond Moore's incredible songwriting and Harrison Calloway, Junior Lowe and the rest of the Fame Gang's tight playing on here, I think this record stands up with the best of the 'second rhythm section' stuff. I just love it. That summer of 1970, with Clarence Carter's Patches hitting the top 5 on the pop charts for Atlantic and Candi's breaking into the pop top 40 herself, may just have been the best of times for Fame. When the studio's two biggest stars got married in August, it made headlines throughout the soul universe. Rick Hall was a happy camper.

That summer of 1970, with Clarence Carter's Patches hitting the top 5 on the pop charts for Atlantic and Candi's breaking into the pop top 40 herself, may just have been the best of times for Fame. When the studio's two biggest stars got married in August, it made headlines throughout the soul universe. Rick Hall was a happy camper.When big stars like The Osmonds began coming down there to record, and turning George Jackson compositions like One Bad Apple into mega-blockbuster hits, Rick couldn't help but see where the money was in 'the business'. He began neglecting his R&B artists, and had shut down the house label entirely by the end of 1973. He negotiated a contract for Candi with Warner Brothers, and agreed to continue producing her for the big company. Her first single for the label, As Long As He Takes Care Of Home, was a top ten R&B hit in the fall of 1974, and it seemed the arrangement was going to work out fine. Despite the words Candi was singing, when she found out Clarence had been cheating on her she divorced him by the end of the year.

As disco began coming in, Hall's brand of southern soul was dropping out of favor, and the sales of Candi's singles slowed way down. Warner Brothers eased her away from Fame and sent her out to L.A. to work with producer David Crawford. She had re-married by then, to a man she later described as a "pimp and a hustler" whose escalating violence and drug use had her scared for her life. She poured her heart out to Crawford, and the song that he wrote for her, Young Hearts Run Free, became an instant classic. The little girl from Alabama was suddenly squarely in the middle of the whole 'pagne and 'caine mirrored ball disco club scene. The song would hit the pop top 20 in early 1976, and spend over 5 months on the charts on its way to #1 on both the R&B and (Billboard's new) Disco charts. Candi Staton was as popular in that world as both Donna Summer and Gloria Gaynor... she was bad.

As disco began coming in, Hall's brand of southern soul was dropping out of favor, and the sales of Candi's singles slowed way down. Warner Brothers eased her away from Fame and sent her out to L.A. to work with producer David Crawford. She had re-married by then, to a man she later described as a "pimp and a hustler" whose escalating violence and drug use had her scared for her life. She poured her heart out to Crawford, and the song that he wrote for her, Young Hearts Run Free, became an instant classic. The little girl from Alabama was suddenly squarely in the middle of the whole 'pagne and 'caine mirrored ball disco club scene. The song would hit the pop top 20 in early 1976, and spend over 5 months on the charts on its way to #1 on both the R&B and (Billboard's new) Disco charts. Candi Staton was as popular in that world as both Donna Summer and Gloria Gaynor... she was bad. Songs like Victim and Looking For Love seemed to tell more of her increasingly troubled life story. By now an alcaholic and serious cocaine addict, she found herself married to a fellow user. Warner Brothers let her out of her contract to record for Sylvia Robinson's Sugar Hill label in 1981. Even though they had brought Dave Crawford back in as producer, the resulting album didn't do much. By 1982, Candi says she had bottomed out both personally and professionally.

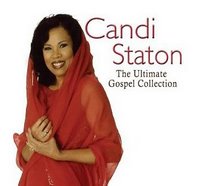

Songs like Victim and Looking For Love seemed to tell more of her increasingly troubled life story. By now an alcaholic and serious cocaine addict, she found herself married to a fellow user. Warner Brothers let her out of her contract to record for Sylvia Robinson's Sugar Hill label in 1981. Even though they had brought Dave Crawford back in as producer, the resulting album didn't do much. By 1982, Candi says she had bottomed out both personally and professionally. That's when the Lord stepped back in. Both Candi and her husband were 'born again', and she turned back to the God she had sworn to forget. The couple would open Beracah Ministries just outside of Atlanta and Staton continued to produce great records. Her first Gospel LP, Make Me An Instrument, made up of her own compositions, was one of the first 'Contemporary Christian' records, and broke into the top ten on the Gospel album charts. Despite a Grammy nomination, Candi still found it hard to be accepted by the Black Gospel world from which she had come. It was Tammy Faye Bakker that first reached out to her, and she has been the host of her own TV show on the Trinity Network, Say Yes, for over 20 years. The best of her Beracah material has been collected on a great 2 CD set.

That's when the Lord stepped back in. Both Candi and her husband were 'born again', and she turned back to the God she had sworn to forget. The couple would open Beracah Ministries just outside of Atlanta and Staton continued to produce great records. Her first Gospel LP, Make Me An Instrument, made up of her own compositions, was one of the first 'Contemporary Christian' records, and broke into the top ten on the Gospel album charts. Despite a Grammy nomination, Candi still found it hard to be accepted by the Black Gospel world from which she had come. It was Tammy Faye Bakker that first reached out to her, and she has been the host of her own TV show on the Trinity Network, Say Yes, for over 20 years. The best of her Beracah material has been collected on a great 2 CD set. As part of her TV ministry, Candi agreed to record an inspirational song for a much publicized Dick Gregory weight loss campaign for a 1000 lb man named David Ron High. The song, You Got The Love, managed to crack the R&B hot 100 in 1986, with it's catchy 'sometimes I feel like throwing my hands up in the air' chorus. Unknown to her, a 'house-music' remix of the song began setting the UK club scene on fire. John Truelove released it, and it went to #4 on the British pop chart in 1991. Truelove's The Source would remix it yet again, and take this remarkable record to #3 in 1997. Candi, frankly bemused by all of this, was back on top in London.

As part of her TV ministry, Candi agreed to record an inspirational song for a much publicized Dick Gregory weight loss campaign for a 1000 lb man named David Ron High. The song, You Got The Love, managed to crack the R&B hot 100 in 1986, with it's catchy 'sometimes I feel like throwing my hands up in the air' chorus. Unknown to her, a 'house-music' remix of the song began setting the UK club scene on fire. John Truelove released it, and it went to #4 on the British pop chart in 1991. Truelove's The Source would remix it yet again, and take this remarkable record to #3 in 1997. Candi, frankly bemused by all of this, was back on top in London. She agreed to make an album of 'inspirational dance music' in 1999 with famed UK producers K-Klass. The record, Outside In, was a huge success, and put no less than three singles in the top 40 in England. Back home in the States, meanwhile, these club records hadn't even been released, and rumors spread that Candi had 'backslid' once again to the secular side. When the HBO series Sex And The City used The Source version of You Got The Love on their series finale in 2004, Americans finally began to take notice.

She agreed to make an album of 'inspirational dance music' in 1999 with famed UK producers K-Klass. The record, Outside In, was a huge success, and put no less than three singles in the top 40 in England. Back home in the States, meanwhile, these club records hadn't even been released, and rumors spread that Candi had 'backslid' once again to the secular side. When the HBO series Sex And The City used The Source version of You Got The Love on their series finale in 2004, Americans finally began to take notice. Her critically acclaimed effort His Hands, released just this past April, is nothing short of a masterpiece. Candi's own compositions stand right up there with great songs by Merle Haggard, Tommy Tate, and Will Oldham. Muscle Shoals keyboard legend Barry Beckett was coaxed out of 'retirement' by producer Mark Nevers, and two of Candi's children join her on the album. The project was brought together by Honest Jon's honcho Mark Ainley, who had released a double LP of Staton's Fame material late last year. He has said that all he wants is to help get Candi Staton the respect she deserves. Touring this past Summer to sold out houses in support of the record, it looks like she may finally be getting it.

Her critically acclaimed effort His Hands, released just this past April, is nothing short of a masterpiece. Candi's own compositions stand right up there with great songs by Merle Haggard, Tommy Tate, and Will Oldham. Muscle Shoals keyboard legend Barry Beckett was coaxed out of 'retirement' by producer Mark Nevers, and two of Candi's children join her on the album. The project was brought together by Honest Jon's honcho Mark Ainley, who had released a double LP of Staton's Fame material late last year. He has said that all he wants is to help get Candi Staton the respect she deserves. Touring this past Summer to sold out houses in support of the record, it looks like she may finally be getting it.She's Got The Love!