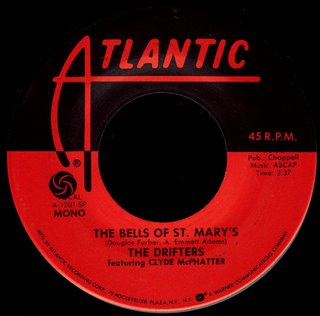

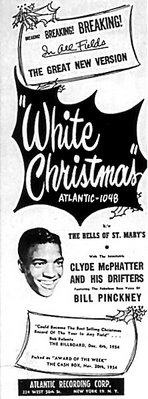

The Bell's Of St. Mary's

The Bell's Of St. Mary'sYou know, the

Ahmet Ertegun (and

Atlantic Records) story is just so

huge, I think it makes sense to break it down into smaller pieces.

Nesuhi Ertegun

Nesuhi Ertegun took his younger brother Ahmet to see

Cab Calloway and

Duke Ellington in London in 1932, and ignited a lifelong love affair with African-American music. By the time the brothers reached their twenties, they had amassed a legendary record collection of over 20,000 jazz and blues 78s. Living in Washington DC, they were frequent visitors to the

Howard Theater, and often invited their favorite musicians 'home' to the Turkish Embassy for Sunday luncheons and impromptu jam sessions. Before long, the brothers were promoting concerts of their own featuring artists like

Leadbelly and

Big Joe Turner (For more on these early years, please check out Rob Whatman's excellent

Living In A Hopeful Future post on

Brown Eyed Handsome Man).

A frequent visitor to those concerts was kindred soul

Herb Abramson. He'd often hang around afterwards and talk through the night about their shared passion for American roots music. One of the places they hung out was 'Waxie Maxie's' Quality Music, a record store where they'd become Max Silverman's best customers. Abramson, who was studying to become a dentist, was also working part time as an A&R man for

National Records. He and Ahmet convinced Silverman to back them and started up

Jubilee Records in 1946. They cut a few Gospel sides and, when the records went nowhere, Waxie Maxie backed out of the deal. Herb sold Jubilee to

Jerry Blaine the following year to help raise money for their new label, Atlantic.

They would borrow the rest of the money from the Ertegun's Turkish dentist, and Atlantic held it's first recording session in November of 1947. They ran the company out of a fleabag hotel on 56th street in Manhattan, with Herb's wife helping to make things work. Faced with an imminent Musicians' Union strike in 1948, the fledgling label recorded some 65 sides by the end of the year. They couldn't give them away.

Abramson had been working with

Jesse Stone at National, and asked him to come and join Atlantic as an arranger. Stone was from Kansas City, and his

Blue Serenaders had first recorded for Okeh back in 1927 (a record which the Erteguns owned, no doubt). It was Duke Ellington who brought him to Harlem, and got him a gig at the Cotton Club in 1936. His skills as an arranger and composer (he reportedly studied with

Cole Porter around this time) kept him in demand uptown, with folks like

Chick Webb and

Louis Jordan using his charts.

Benny Goodman took

Idaho, a Stone composition, all the way to #4 on the pop charts in 1942. A deeply influential figure, the Atlantic story doesn't really begin until Jesse Stone comes on board.

He accompanied Ertegun and Abramson on a trip down south in 1949 to try and figure out why their records weren't selling. A productive journey, they would find Blind Willie McTell playing on the streets of Atlanta and Professor Longhair doing his thing just outside of New Orleans (check out Dan Phillips' cool

Goin' To Night School post over at

Home Of The Groove for more on the 'Fess story). More importantly, Stone noticed that the kids in the clubs were 'dancing different' than they had before, and he hatched an idea for a new bassline and backbeat rhythm that would make Atlantic's records more 'danceable'. This may have been the moment when Rock & Roll was born.

One of the first songs to feature Stone's new concept was

Ruth Brown's

Teardrops From My Eyes, which would soar to #1 R&B in the fall of 1950. This record really introduced 'the sound' that came to define an Atlantic production. Ertegun has said that most of the people in the record business at the time were in it simply as a means to make money, and couldn't have cared less about the music. He changed all that by bringing his impeccable taste to bear, and raising the quality of their 'product' (which just happened to be black American music) to a new level. His connections in the jazz world enabled him to hire the best studio musicians (like

Mickey Baker on guitar,

Sam 'The Man' Taylor on sax, and future

Modern Jazz Quartet drummer

Connie Kay), and Atlantic's records showed it. They also were the first in the industry to pay their artists 'performance royalties', which helped to attract the talent as well.

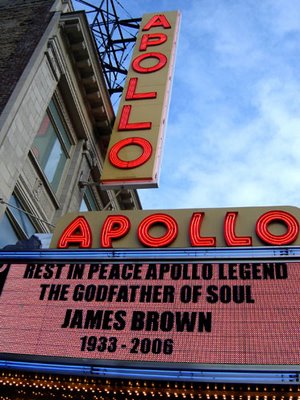

Unable to interest good songwriters in taking a chance on his largely unknown new label, Ahmet began writing the songs himself, under the pseudonym A. Nugetre - Ertegun spelled backwards (please check out Rob Whatman's ongoing

Nugetre's Nuggets series for more info on his compositions). Around this same time, Ertegun went to see Big Joe Turner sing with the

Count Basie Orchestra at the Apollo. He and Basie's Band weren't 'clicking', and the merciless uptown crowd essentially booed Turner off the stage. Ahmet found him down the street at a hole-in-the-wall bar, and offered him a contract with Atlantic. He gave Big Joe one of his 'nuggets' to record,

Chains Of Love, and the bluesy Jesse Stone arrangement spent a

month at the #2 position on the national R&B charts in the summer of 1951. The only thing that kept it from the top slot was

The Dominoes' absolutely gigundo smash hit,

Sixty Minute Man.

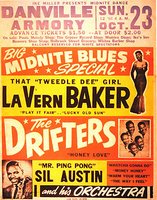

Billy Ward

Billy Ward was a Juilliard trained pianist and arranger who gave voice lessons on the side. He had been working with the

Mount Lebanon Singers, a harlem Gospel quartet, and formed an R&B vocal group called The Ques around two members of the quartet,

Charlie White and

Clyde McPhatter. The group won the fabled 'amateur night' at The Apollo, and also an 'Arthur Godfrey Talent Scouts' competition in 1950.

Ralph Bass signed them to his new Federal label (a subsidiary of King Records), and changed their name to The Dominoes. Their first single,

Do Something For Me, with McPhatter on the lead vocal, went to #6 R&B, but it was the

Bill Brown led

Sixty Minute Man that busted things wide open. Ertegun went to see them at the Apollo, and says that when he heard Clyde McPhatter sing he "fell off his chair."

Clyde's lead vocal on the incredible

Have Mercy Baby captivated the nation, and put The Dominoes at the top of the charts for ten weeks in the summer of 1952. Billy Ward, apparently quite the egotist, refused to give Clyde any credit for the group's success, and kept him on a salary of $100 a week. He was not a happy camper. When Ertegun went to see them at Birdland in NYC in May of 1953, he was astonished to learn that Ward had fired McPhatter a few days before for 'breaking band rules'. He ran outside, found a phone book and started calling the McPhatters he found listed in Harlem. Once he got him on the phone, Clyde readily agreed to sign with Atlantic, as long as Ahmet ironed it all out with Federal.

Herb Abramson, valuable for his dentistry skills, was drafted into The Army at about the same time. Realizing they would need help while he was gone, he and Ahmet approached Billboard Magazine writer

Jerry Wexler about working with them. Always the operator, Wexler asked for a share in the company first, and they gave him a 13% interest in the label for about $2000 (which they then used to buy Jerry a company Cadillac).

One of Wexler's first sessions was with Clyde and a group of friends he brought downtown from Harlem in June of 1953. Telling Clyde the group needed 'more bottom', he sent him back home to work on their sound. Instead, Mcphatter used his Gospel connections to put together an altogether different bunch of singers that included brothers

Bubba and Gerhart Thrasher who had been singing as

The Thrasher Wonders. Clyde's new group, now formally known as

The Drifters, also included

Willie Ferber and

Bill Pinkney. Jesse Stone had written an amazing song with Clyde in mind, and drilled the group on the arrangement for weeks. When they entered the studio in August, they were ready. The positively brilliant

Money Honey became the Drifters first single and just took off, spending 11 weeks at #1 R&B that fall.

At this point, Willie Ferber was in an accident, and left the group before their next sessions for the label in November. The rhumba-flavored

Such A Night would beat out

Dinah Washington's version in the charts as the follow-up, and the group was in demand. The B side of that record,

Lucille, had actually been recorded with the first group Mcphatter brought to Atlantic, and went to #7 on its own in early 1954. The Drifters were scheduled for their next recording date in February, and Wexler was working on material. He and McPhatter came up with another smash, the suggestive

Honey Love. The fact that the record was banned from airplay by many radio outlets helped keep it at #1 for two months that summer. Jesse Stone's magic touch was paying off once again! A 'nugget' Ertegun wrote for the session,

What'Cha Gonna Do, would become the basis for the 'Twist' craze of a few years later.

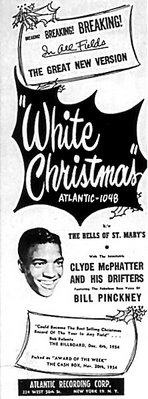

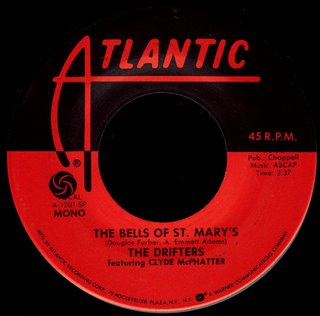

That incredible recording session (engineered by

Tom Dowd in the Atlantic offices, with the desks pushed out of the way) would also produce the timeless

White Christmas and our present b side,

The Bells Of St. Mary's. Bill Pinkney's bass lead on White Christmas has become one of the truly great moments in holiday R&B, and still blows me away every time I hear it. The arrangement was based on

The Ravens' version of a few years earlier, but the sheer talent, and flawless production of this record has kept it in the mix for over 50 years! It would go to #2 that December, then #5 again the following year, and so on... making Atlantic 1048 one of the company's biggest sellers ever, as they continued to release it every year (as you may have noticed, the copy we have up here today hails from some time in the '80s, and is on loan from the ol' jukebox).

I never understood what

The Bells Of St. Mary's had to do with Christmas music... it just may be the fact that it was the B side of this giant 45 that put it up there in the canon of carols, I don't know. A World War I era sentimental favorite, made popular again by a World War II era Bing Crosby film, this song packs some juice! I absolutely LOVE the way Jesse Stone drops the background singers down to a hushed minor keyed wail there after the break (used to great effect by

Martin Scorsese in

Goodfellas, I might add). Spine tingling stuff, man.

Now, I know there's a LOT more to say here, not only about Atlantic, but about Clyde McPhatter (who started his solo career shortly after this record was released), and The Drifters (who would go on to make some of Atlantic's best sides with a totally different line-up) as well. We'll go there together in the coming year.

Things are gettin' kinda crazy around here, just like they do every year about this time, but I'd like to take a moment to extend my warmest wishes to all of you out there on the other side of the screen for a happy and a healthy holiday season... I hope Santa treats ya good!

Merry Christmas from the greatest city in the world.

-red kelly

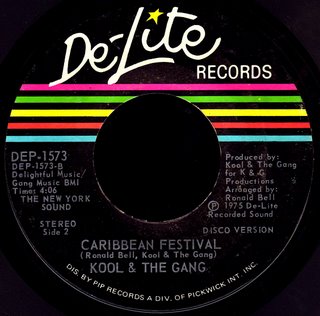

Claydes E.X. Smith was a jazz trained musician who became a founding member of Kool & The Gang. As the co-author of songs like Hollywood Swinging and Jungle Boogie his seminal guitar work helped lay the foundation for the Funk Revolution. Today's B side 'disco version' is taken from the 1975 album Spirit Of The Boogie, and has this sort of NOLA Brass Band 'second-line' feel to it that I just love... check out that smokin' guitar work!

Claydes E.X. Smith was a jazz trained musician who became a founding member of Kool & The Gang. As the co-author of songs like Hollywood Swinging and Jungle Boogie his seminal guitar work helped lay the foundation for the Funk Revolution. Today's B side 'disco version' is taken from the 1975 album Spirit Of The Boogie, and has this sort of NOLA Brass Band 'second-line' feel to it that I just love... check out that smokin' guitar work!