8th Wonder

8th Wonder

In 1943, a Houston sax player named

Illinois Jacquet played a wailin' solo on a Lionel Hampton record called

Flying Home. It would climb to #3 on the 'race record' charts, and is considered by some to be the

first rock & roll record. That honkin' and hollerin' vamp would spawn a whole generation of 'bar-walking' Texas sax players, and the joint was jumpin'. Growing up outside of Dallas, two young kids were paying attention. Coming up out of their respective High School Bands,

Grady Gaines would go on to lead

Little Richard's fabled

Upsetters, while a young

Curtis Ousley took off for New York.

Ousley landed a job in the band of

Sam 'The Man' Taylor, who had been instrumental in creating Atlantic Records trademark sound with his elemental saxophone work on early R&B sides by

Ruth Brown and

Joe Turner. Curtis would continue that tradition, becoming their new 'go-to guy', laying down those stammerin', stutterin' solos on big hits by

The Coasters,

Chuck Willis and

Clyde McPhatter. His own

ATCO sides from this period (recorded under the stage name he'd been using since high school,

King Curtis), went nowhere, as did an album called

Have Tenor Sax Will Blow.

By 1960, he had signed with Prestige, and was exploring his Jazz roots together with great side-men like

Nat Adderley and

Wynton Kelly. In addition to continuing his session work for small labels like Wand/Scepter (think

The Shirelles), he would also release a cool album called

Trouble In Mind in 1961, on which he actually

sings the blues!

Ousley formed a band around this time called

The Noble Knights, that played locally in New York. As we've

mentioned before,

Bobby Robinson heard them playing at

Small's Paradise up in Harlem and bet Curtis he could deliver him a hit record if he let him produce it his way. According to Bobby, that way included a 'less is more' approach that gave the rest of the Knights a chance to stretch out a little bit.

Soul Twist would become the first release on Robinson's

Enjoy imprint, and a massive hit, topping the R&B charts for two weeks in early 1962.

King Curtis set about forming a crack touring band that he would dub

The Kingpins at this point, bringing in great musicians like fellow Texan

Cornell Dupree on guitar.

When Little Richard 'got religion' in 1957, Grady Gaines' Upsetters had gone to work for

Little Willie John. After that arrangement fell apart in early 1962,

Sam Cooke hired them to go out on the road with him. They would share the bill with King Curtis many times that spring, and Sam couldn't help but notice how tight The Kingpins were. Cooke began bugging him about replacing Gaines as his back-up band, but Curtis kept telling him to forget about it, that they were making too much money as freelance studio musicians in New York. Cooke persisted, going so far as to 'name check'

Soul Twist in his top five smash

Having A Party that summer. After ego problems between Sam and certain members of The Upsetters came to a head, Curtis gave in and consented to go out on tour with Cooke in January of 1963.

Lucky for us, RCA recorded a show from that tour down in Miami at a chitlin' circuit joint called

The Harlem Square Club. The

resulting album has recently been remastered, and captures both Sam and Curtis at the height of their game. You should own a copy.

The King signed with Capitol around this time, but his singles failed to even dent the charts. An album called

Country Soul didn't make much noise either. His second album for the label,

Soul Serenade, is an out of print gem. Even though the title track (written by Curtis and Shirelles producer

Luther Dixon) barely made it to #51 R&B in early 1964, it has become one of King Curtis' most enduring songs (...helped in part, I'm sure, by the

great version that

Willie Mitchell took to the R&B top ten in 1968).

By late 1965, King Curtis was back with Atlantic Records, where he would once again become a pivotal part of their sound throughout the 'soul era' at the label. One of the first projects he was involved in was as a producer.

Ray Sharpe, a guitarist friend from his Fort Worth days, had had a minor hit in 1959 with a song called

Linda Lu. Curtis brought him to ATCO, and the 1966 single

Help Me (Get The Feeling) is credited to

Ray Sharpe With the King Curtis Orchestra. That 'orchestra' included a young

Jimi Hendrix. Although the record tanked, the hot backing track would turn up later on (more on that in a minute). His driving sax would help propel

Herbie Mann's

Philly Dog into the R&B top 40 later that year.

His work in the studio brought him in contact with a largely ignored staff arranger named

Arif Mardin, a Turk that

Nesuhi Ertegun had hired and then promptly forgotten about. It was Curtis who brought Mardin's considerable talents to the attention of

Jerry Wexler in 1966. As you

may recall, when

Aretha's Muscle Shoals sessions went south in early 1967, Wexler brought the Fame musicians north, ostensibly to record an album called

King Curtis Plays The Great Memphis Hits. Once that was finished, Wexler hunkered down with Curtis, Mardin and

Tom Dowd to help him finish Aretha's

historic album.

King Curtis was all over it, recycling the Ray Sharpe track from the year before which, with the addition of some new horn charts and lyrics penned by Aretha's sister

Carolyn, would become the cookin'

Save Me. When the crew in the studio was stuck trying to formulate a bridge to round out

Otis Redding's

Respect, it was Curtis who came up with the idea of using the bridge section from

When Something Is Wrong With My Baby, which he had just recorded for the

Memphis Hits album. According to Mardin, "Respect is in C, but that bridge, Curtis' saxophone solo, is in F Sharp - a totally unrelated key, but we liked it! We liked those chords, so we put it in." If that solo was the only thing he ever did, that would be enough for me, man!

Mardin and Ousley became pretty much inseparable from that point on, and worked together on sessions both in New York and Memphis. They recorded the classic

Memphis Soul Stew at

Chips Moman's American Studios in July of 1967. Today's cool B side (the flip of

Theme From the Valley Of The Dolls) was recorded down there that December and, in addition to the usual

Memphis Boys, includes the very cool

Bobby Womack (an American regular himself by then) on guitar. It's got this kind of

Sanford & Son thing goin' on, right? Great stuff.

As the only African American member of the 'inner circle' of producers and arrangers at Atlantic, King Curtis had earned his stripes by consistently adding his own brand of genius to countless sessions over the years. As the decade drew to a close, his own albums like

Instant Groove (on which he would use the Ray Sharpe track once again as the basis for the title cut) and

Get Ready took their place alongside Atlantic's new roster of artists like

Eric Clapton,

Delaney & Bonnie and

The Allman Brothers Band, all of whom revered him.

By 1970, the touring line-up of

The Kingpins had solidified, and in addition to Dupree on guitar, included the legendary

Bernard 'Pretty' Purdie on drums,

Jerry Jemmott on bass, and

Truman Thomas on the keys. Jerry Wexler convinced Aretha Franklin to use them as her back-up band, and booked the whole lot of them into the Fillmore West in February of 1971. The addition of the

Memphis Horns and

Billy Preston on the Hammond organ made for one kickin' band, let me tell ya. The concerts were taped, and spawned two incredible live albums, the aptly titled

Aretha Live At Fillmore West and

King Curtis Live At Fillmore West. Check 'em out!

Curtis had become a top-notch producer by then, and had worked on great albums by

Roberta Flack,

Donnie Hathaway and old Texas pal

Freddie King. In the wake of the Fillmore gigs, he became Aretha's musical director, and was producing a long-awaited

solo album on

Sam Moore.

On August 13th 1971, King Curtis was carrying an air conditioner into his apartment on West 86th Street in Manhattan. Two junkies were sitting on the steps, blocking his way. When he asked them to move, one of them stabbed him in the heart. He was taken to nearby Roosevelt Hospital, but there was nothing they could do.

Atlantic Records closed down their offices on the day of his funeral. Jerry Wexler delivered his eulogy, calling him a "sensitive virtuoso." Aretha Franklin sang the haunting

Never Grow Old. He was buried in a cemetery out on Long Island.

Years later, Aretha had this to say to author

Gerri Hirshey; "King Curtis could make me laugh

so hard... he was a soul superhero, and I miss him still."

Me too.

First off, he said that King Curtis was indeed a guitar player as well as a reed man, and was the guitarist on the 1962 Enjoy release Hot Potato by a group called the Rinkydinks. Oddly enough, that tune would be used as the initial theme song for a newly syndicated TV show called Soul Train in 1971. Ever the entrepreneur, Bobby Robinson changed 'Rinkydinks' to 'Ramrods' and re-released the song as Soul Train (Rampage 1000) in 1972. It would spend five weeks on the Billboard R&B chart that summer, climbing as high as #41... not bad for a ten year old recording!

First off, he said that King Curtis was indeed a guitar player as well as a reed man, and was the guitarist on the 1962 Enjoy release Hot Potato by a group called the Rinkydinks. Oddly enough, that tune would be used as the initial theme song for a newly syndicated TV show called Soul Train in 1971. Ever the entrepreneur, Bobby Robinson changed 'Rinkydinks' to 'Ramrods' and re-released the song as Soul Train (Rampage 1000) in 1972. It would spend five weeks on the Billboard R&B chart that summer, climbing as high as #41... not bad for a ten year old recording! Mr. Simonds goes on to say that it was none other than King Curtis himself who played the guitar on Blue Nocturne, answering the nagging question posed by Larry Grogan last December. Roy was kind enough to send me a copy of his exhaustive Curtis discography, a labor of love compiled over the past thirty-odd years, which details every known session that the King ever played on. A truly amazing document, it chronicles his career in painstaking detail. Today's selection is a case in point:

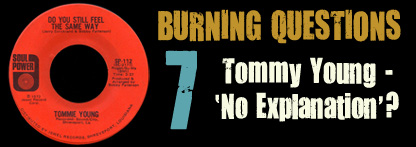

Mr. Simonds goes on to say that it was none other than King Curtis himself who played the guitar on Blue Nocturne, answering the nagging question posed by Larry Grogan last December. Roy was kind enough to send me a copy of his exhaustive Curtis discography, a labor of love compiled over the past thirty-odd years, which details every known session that the King ever played on. A truly amazing document, it chronicles his career in painstaking detail. Today's selection is a case in point: The only other song recorded at the December 5, 1967 American Studio session that produced 8th Wonder, This Is Soul is somewhat of a Curtis rarity, as its only release was as this B side of (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay in early 1968. Top ten hit Memphis Soul Stew was still riding the charts when this session was held and, in the same kind of spoken word rap in which he delivered his famous 'recipe', Curtis details his 'Definition of Soul':

The only other song recorded at the December 5, 1967 American Studio session that produced 8th Wonder, This Is Soul is somewhat of a Curtis rarity, as its only release was as this B side of (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay in early 1968. Top ten hit Memphis Soul Stew was still riding the charts when this session was held and, in the same kind of spoken word rap in which he delivered his famous 'recipe', Curtis details his 'Definition of Soul': Also, in that last post I mentioned the Sam Moore solo album that King Curtis was producing when he was killed. For whatever reasons, Atlantic didn't release it at the time, and the tapes gathered dust in a vault somewhere for over thirty years. It was finally released as Plenty Good Lovin' in 2002 by an outfit called 2K Sounds, and I just picked up a copy. Let me tell ya something, with King Curtis producing and blowing 'dat horn and both Aretha Franklin and Donny Hathaway on keyboards, the record just COOKS! Get yourself a copy.

Also, in that last post I mentioned the Sam Moore solo album that King Curtis was producing when he was killed. For whatever reasons, Atlantic didn't release it at the time, and the tapes gathered dust in a vault somewhere for over thirty years. It was finally released as Plenty Good Lovin' in 2002 by an outfit called 2K Sounds, and I just picked up a copy. Let me tell ya something, with King Curtis producing and blowing 'dat horn and both Aretha Franklin and Donny Hathaway on keyboards, the record just COOKS! Get yourself a copy.