Robert Parker - All Nite Long (Part 2) (Ron 327)

All Nite Long (Part 2)

The centerpiece of this year's fabulous Ponderosa Stomp was the incredible performance of Wardell Quezergue's New Orleans Rhythm & Blues Revue.

Wardell has put together a tight band that's been playing his latest arrangements on various dates in the Crescent City (most recently at the French Quarter Fest). Along with featured vocalist Tony Owens, Sam Henry Jr. on keyboards, and Wardell's son on the bass, this horn heavy outfit has just been rocking the town. At the Stomp, the horn line was joined by the great Herb Hardesty and a host of other members of the local brass. If you were a musician in New Orleans that night, this was where you wanted to be.

Wardell has put together a tight band that's been playing his latest arrangements on various dates in the Crescent City (most recently at the French Quarter Fest). Along with featured vocalist Tony Owens, Sam Henry Jr. on keyboards, and Wardell's son on the bass, this horn heavy outfit has just been rocking the town. At the Stomp, the horn line was joined by the great Herb Hardesty and a host of other members of the local brass. If you were a musician in New Orleans that night, this was where you wanted to be. The reason for that was a very rare appearance by the man who started it all, Dave Bartholomew. As the writer and producer of so many great Imperial sides throughout the fifties, he laid the groundwork for just about everything that was to follow (we'll talk more about all of that in a future post). When Allen Toussaint showed up and sat in on the Hammond Organ, and later spoke to the crowd about the importance of both Bartholomew and Quezergue, I felt truly honored to be there that night.

The reason for that was a very rare appearance by the man who started it all, Dave Bartholomew. As the writer and producer of so many great Imperial sides throughout the fifties, he laid the groundwork for just about everything that was to follow (we'll talk more about all of that in a future post). When Allen Toussaint showed up and sat in on the Hammond Organ, and later spoke to the crowd about the importance of both Bartholomew and Quezergue, I felt truly honored to be there that night. Jean Knight was also on the bill, and hearing her perform Mr. Big Stuff with the man whose arrangement took it all the way to #1 R&B in 1971 was just great. What blew me away, however, was the unannounced appearance of the legendary Robert Parker. Now 77 years old, I hadn't heard anything about him in years. Watching him tear into Barefootin' made me feel like I did almost forty years ago when I first heard it on the radio... really happy. This was truly a rare treat, man, and kudos go to the Mystic Knights for pulling it off.

Jean Knight was also on the bill, and hearing her perform Mr. Big Stuff with the man whose arrangement took it all the way to #1 R&B in 1971 was just great. What blew me away, however, was the unannounced appearance of the legendary Robert Parker. Now 77 years old, I hadn't heard anything about him in years. Watching him tear into Barefootin' made me feel like I did almost forty years ago when I first heard it on the radio... really happy. This was truly a rare treat, man, and kudos go to the Mystic Knights for pulling it off. As these things happen, I had just gotten a double dose of Robert Parker 45s laid on me before I left by my all-time favorite vinyl maven, Diggin' Dave of Illinois, so I figured it was time to check things out.

Parker came up idolizing Louis Jordan and decided to take up the saxophone in the Booker T. Washington High School Band. As he told Jeff Hannusch a few years ago, "Everybody I hung around with in my neighborhood played music - June Gardner, Huey Smith, Lee Diamond, Sugar Boy Crawford, Big Boy Myles, Danny White, and Irving Bannister. Guys like Fats Domino, Dave Bartholomew, and Professor Longhair would come to our neighborhood looking for musicians." That must have been some neighborhood, huh?

Parker came up idolizing Louis Jordan and decided to take up the saxophone in the Booker T. Washington High School Band. As he told Jeff Hannusch a few years ago, "Everybody I hung around with in my neighborhood played music - June Gardner, Huey Smith, Lee Diamond, Sugar Boy Crawford, Big Boy Myles, Danny White, and Irving Bannister. Guys like Fats Domino, Dave Bartholomew, and Professor Longhair would come to our neighborhood looking for musicians." That must have been some neighborhood, huh? When Parker was eighteen years old, he sat in with Professor Longhair at The Caldonia Inn, and Fess hired him on the spot, taking him along on his regular gig at The Pepper Pot across the river in Gretna. This was the place where Mardi Gras In New Orleans was born, and where, as one of Longhair's 'Shuffling Hungarians', Parker has said he "learned the ropes". In 1949, Longhair made his first recordings (for the short-lived Star Talent label), and Parker was there. He was also there a year later when Fess signed with Mercury, reportedly just hours before he was approached by the young Ahmet Ertegun, who would record him for Atlantic anyway.

When Parker was eighteen years old, he sat in with Professor Longhair at The Caldonia Inn, and Fess hired him on the spot, taking him along on his regular gig at The Pepper Pot across the river in Gretna. This was the place where Mardi Gras In New Orleans was born, and where, as one of Longhair's 'Shuffling Hungarians', Parker has said he "learned the ropes". In 1949, Longhair made his first recordings (for the short-lived Star Talent label), and Parker was there. He was also there a year later when Fess signed with Mercury, reportedly just hours before he was approached by the young Ahmet Ertegun, who would record him for Atlantic anyway. Parker next took up residency at the fabled Club Tiajuana in New Orleans, where he led the house band for over five years. "I was a showman." he said, "I walked the bar, took my horn out in the audience and played under the tables on my back..." (that's Robert pictured on the left, with fellow 'bar-walker' Lonnie Bolden on the right). He backed everybody that came through there, and became known as the 'go-to' tenor man in town. He did stints with Tommy Ridgley's Untouchables and Huey Smith's Clowns before going on the road with Eddie Bo in the late fifties. Bo had just waxed the seminal I'm Wise for Apollo Records, and included Parker in his touring band that went on to back other national acts like Amos Milburn, Charles Brown, and Big Joe Turner.

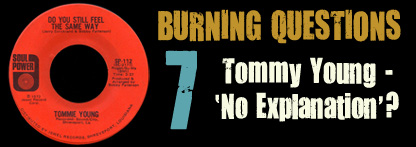

Parker next took up residency at the fabled Club Tiajuana in New Orleans, where he led the house band for over five years. "I was a showman." he said, "I walked the bar, took my horn out in the audience and played under the tables on my back..." (that's Robert pictured on the left, with fellow 'bar-walker' Lonnie Bolden on the right). He backed everybody that came through there, and became known as the 'go-to' tenor man in town. He did stints with Tommy Ridgley's Untouchables and Huey Smith's Clowns before going on the road with Eddie Bo in the late fifties. Bo had just waxed the seminal I'm Wise for Apollo Records, and included Parker in his touring band that went on to back other national acts like Amos Milburn, Charles Brown, and Big Joe Turner. When Bo signed with Joe Ruffino's upstart Ric and Ron labels in 1959, he took Robert with him. Parker credits Eddie with helping him develop his own style, telling him "Do your own thing, man. Play what you feel." This red-hot cut we have here today is the B side of Parker's first release under his own name. According to John Broven, it was produced by dee-jay Larry McKinley, who shares writer's credit with Parker on the A side. Here on the B, however, you'll note that it's written by 'Parker-Bocage-Rebennack'. Bocage being, of course, Eddie Bo, and Rebennack none other than an eighteen year old Doctor John. That's him playing that wild electric guitar, which was his primary instrument in those days. You go, Max!

When Bo signed with Joe Ruffino's upstart Ric and Ron labels in 1959, he took Robert with him. Parker credits Eddie with helping him develop his own style, telling him "Do your own thing, man. Play what you feel." This red-hot cut we have here today is the B side of Parker's first release under his own name. According to John Broven, it was produced by dee-jay Larry McKinley, who shares writer's credit with Parker on the A side. Here on the B, however, you'll note that it's written by 'Parker-Bocage-Rebennack'. Bocage being, of course, Eddie Bo, and Rebennack none other than an eighteen year old Doctor John. That's him playing that wild electric guitar, which was his primary instrument in those days. You go, Max! The fact that this same trio would go on to appear on so many of those classic Ric and Ron sides (like Don't Mess With My Man, Carnival Time, A Losing Battle, and Go To The Mardi Gras) is simply amazing. Parker signed with local promoter Percy Stovall around this time, and formed a band called Robert Parker and the Royals that backed up Stovall's other clients (like Johnny Adams, Irma Thomas and Chris Kenner) all along the gulf coast 'circuit'. After one more release on Ron, he signed on with old friend Dave Bartholomew on Imperial in 1962. This arrangement produced three singles, none of which went anywhere. By 1963, the bottom seemed to drop out of the New Orleans R&B scene, and Parker took a job as an orderly at Charity Hospital, while still playing whatever gigs came along.

The fact that this same trio would go on to appear on so many of those classic Ric and Ron sides (like Don't Mess With My Man, Carnival Time, A Losing Battle, and Go To The Mardi Gras) is simply amazing. Parker signed with local promoter Percy Stovall around this time, and formed a band called Robert Parker and the Royals that backed up Stovall's other clients (like Johnny Adams, Irma Thomas and Chris Kenner) all along the gulf coast 'circuit'. After one more release on Ron, he signed on with old friend Dave Bartholomew on Imperial in 1962. This arrangement produced three singles, none of which went anywhere. By 1963, the bottom seemed to drop out of the New Orleans R&B scene, and Parker took a job as an orderly at Charity Hospital, while still playing whatever gigs came along. When Wardell Quezergue started up his NOLA label in 1964, Parker began doing some session work for him. He remembered something the always entertaining Chris Kenner had said to the audience one night while he was playing behind him out on the road; "Hey everybody, get on your feet. You make me nervous when you're in your seats", and he began developing an idea for a song based on that. Wardell recorded Parker's Barefootin' in 1965, and used it as a demo to try and interest other artists in singing it. When nobody went for it, he finally released Parker's own version in the spring of 1966. It just took off, spending 17 weeks on the charts while going to #2 R&B (kept from the top slot by the mighty When A Man Loves A Woman), and breaking into the top ten Pop... Just a MONSTER of a song. In some ways, I don't think NOLA (or Parker himself, for that matter) was prepared for such overnight success, and they had a hard time keeping up with demand.

When Wardell Quezergue started up his NOLA label in 1964, Parker began doing some session work for him. He remembered something the always entertaining Chris Kenner had said to the audience one night while he was playing behind him out on the road; "Hey everybody, get on your feet. You make me nervous when you're in your seats", and he began developing an idea for a song based on that. Wardell recorded Parker's Barefootin' in 1965, and used it as a demo to try and interest other artists in singing it. When nobody went for it, he finally released Parker's own version in the spring of 1966. It just took off, spending 17 weeks on the charts while going to #2 R&B (kept from the top slot by the mighty When A Man Loves A Woman), and breaking into the top ten Pop... Just a MONSTER of a song. In some ways, I don't think NOLA (or Parker himself, for that matter) was prepared for such overnight success, and they had a hard time keeping up with demand. In any event, Parker was soon headlining at The Apollo, and would go on to dominate the label's releases from that moment on. As often happens, they were unable to duplicate that kind of smash, and managed to place only one more of Parker's eleven singles (Tip Toe) in the R&B top fifty the following year. Please be sure and check out Larry Grogan's excellent article on Parker's NOLA period over at the Funky 16 Corners.

In any event, Parker was soon headlining at The Apollo, and would go on to dominate the label's releases from that moment on. As often happens, they were unable to duplicate that kind of smash, and managed to place only one more of Parker's eleven singles (Tip Toe) in the R&B top fifty the following year. Please be sure and check out Larry Grogan's excellent article on Parker's NOLA period over at the Funky 16 Corners. As we've mentioned recently, NOLA went out of business when it got caught up in the collapse of Cosimo Matassa's Dover Records in 1968. By 1970, Parker was 'back on Bourbon Street' working in Clarence 'Frogman' Henry's band. He did some work with Allen Toussaint around this time as well, whose Sansu Productions leased a couple of singles to Shelby Singleton's family of labels. For more on that part of the story, please head on over to Dan Phillips' cozy Home Of The Groove. He would reunite with Wardell Quezergue for a few more singles on Island in the mid-seventies, most notably with A Little Bit Of Something (Is Better Than A Whole Lot Of Nothing) in 1974.

As we've mentioned recently, NOLA went out of business when it got caught up in the collapse of Cosimo Matassa's Dover Records in 1968. By 1970, Parker was 'back on Bourbon Street' working in Clarence 'Frogman' Henry's band. He did some work with Allen Toussaint around this time as well, whose Sansu Productions leased a couple of singles to Shelby Singleton's family of labels. For more on that part of the story, please head on over to Dan Phillips' cozy Home Of The Groove. He would reunite with Wardell Quezergue for a few more singles on Island in the mid-seventies, most notably with A Little Bit Of Something (Is Better Than A Whole Lot Of Nothing) in 1974. The continued popularity of the irresistible Barefootin' (it was used in a Spic 'n' Span commercial in 1983, and re-released in the UK in 1987) has kept Robert Parker's name in the public eye. It has also, in my opinion, contributed to the idea that he is little more than a 'one hit wonder'.

The continued popularity of the irresistible Barefootin' (it was used in a Spic 'n' Span commercial in 1983, and re-released in the UK in 1987) has kept Robert Parker's name in the public eye. It has also, in my opinion, contributed to the idea that he is little more than a 'one hit wonder'. He is so much more than that.