Cheater Man

Cheater Man

Johnny Otis

Johnny Otis came up in the 1920s in Berkley, the son of a Greek immigrant grocery store owner. By the time he was eighteen, he was the drummer in a local swing band,

Count Otis Matthew's House Rockers. Following the music to Los Angeles, he started his own outfit, and by 1945 had made a name for himself on the red hot R&B scene. Within a few years, he had opened up his own club, the fabled

Barrelhouse, which would become

the number one spot for what was happening in black music on the west coast.

Born in Texas,

Esther Mae Jones grew up splitting her time between her father in Houston and her mother out in Los Angeles. Already noted for singing in the Church, her sister urged her to enter the weekly amateur talent competitions that Otis held at The Barrelhouse. She was thirteen years old. Johnny, and everybody else at the club, were just knocked out by the pipes on this kid, and he brought her into the studio to record two sides for Modern, which went unreleased at the time.

Convinced '

Little Esther' was a star, he added her to his live revue, and signed a deal with

Herman Lubinsky's Savoy imprint in 1950. Their first single for the label,

Mistrustin' Blues, was just a monster, spending

nine weeks at number one, and making Esther the youngest person to ever have a #1 R&B hit. The public just couldn't get enough, and all six of the other singles released by Savoy on her that year hit the top ten, including two more that made number one. She had started out her career at the very top.

Little Esther was in demand, and she (accompanied by her mother) spent 1950 out touring with the Johnny Otis band. Billed as the

Savoy Records Barrelhouse Caravan Of Stars, the revue also included

Mel Walker and

The Robins (the group that would later become

The Coasters). in 1951, Little Esther would sue Savoy for non-payment of royalties, and sign on with

Syd Nathan at Federal.

Although she continued to perform to sold out houses across the nation with the Otis band, for whatever reason, her Federal sides (with the exception of

Ring-A-Ding-Doo which went to #8 in early 1952) weren't doing much. In 1953, she parted ways with Johnny Otis, and began touring the chitlin' circuit with folks like

H-Bomb Ferguson and

Willie Mae Thornton. By the mid-fifties, Esther had switched labels once again, but her Decca sides sank like a stone. By the end of the decade, her personal appearances had become few and far between, and she had all but faded from the public eye. Reportedly fighting a major battle with heroin addiction, she moved back to Texas to be close to her father.

Performing at local clubs to make ends meet, Esther (who had by then begun using the last name Phillips) shared the bill with an up and coming singer by the name of

Kenny Rogers one night in 1962 (you can't make this stuff up). Kenny brought his brother

Leland to see her (just as he would do with

Bettye Lavette a few years later), and he was knocked out.

Ray Charles' landmark album,

Modern Sounds In Country and Western Music, was all the rage that year, and the single of

I Can't Stop Loving You taken from the Lp owned the number one slot all summer long. Leland decided to take Esther to Nashville to record.

Along with partner

Bob Gans, he started up the Lenox label and, in what proved to be a stroke of genius, recorded Esther's own country album,

Reflections Of Country and Western Greats with

Cliff Parman and the

Anita Kerr Singers. Released as a single in November of 1962,

Release Me went straight to number one R&B and stayed there for three weeks. Incredibly, 'Little' Esther Phillips was back on top. Four more singles would follow (including a duet with

Big Al Downing), but none of them went anywhere and, by late 1963, Lenox was out of business.

Signed By

Ahmet Ertegun (who said she had "one of the best voices I've ever heard") to Atlantic in 1964, they seemed unsure of what to do with her. In the midst of the 'British Invasion', the label eventually hit paydirt in early 1965 with Esther's great rendition of

And I Love Him, a feminized version of the Beatles' hit from the year before, which just missed the R&B top ten. Apparently hoping that lightning would strike twice in the same place, the label re-released her Lenox Lp as

The Country Side of Esther Phillips in 1966. It bombed, as did an attempt to go back to her R&B roots,

Confessin' The Blues.

Although

When A Woman Loves A Man, a gender-reversed answer song to

Percy Sledge's smash hit, broke into the R&B top thirty in May of 1966, it wasn't until almost a year later (after

Jerry Wexler had worked his magic on

Aretha Franklin) that Atlantic decided to try and record Esther as a soul artist. Today's cool selection, the flip of a remake of

Brenda Lee's 1960 #1 pop hit

I'm Sorry (see what I mean?), is the result of that attempt. Before we talk about that, though, I'd like to take a closer look at the short-lived collaboration between two soul legends,

Dan Penn and

Chips Moman.

As we've discussed before, Penn left Fame sometime in the summer of 1966, and started hanging around Moman's American Studio in Memphis. They traveled together to a notorious 'Disk Jockey Convention' in Nashville, where they got involved in a poker game with our man

Papa Don Schroeder. Moman, as usual, was winning. During breaks in the game, he and Penn worked on writing what they conceived as 'the greatest cheating song ever',

The Dark End Of The Street. Goldwax owner

Quinton Claunch heard what they were up to and offered them the use of his room next door, if they promised him the song for

James Carr. They accepted, and when they had finished the song, Penn convinced Moman to let Papa Don win back his money. Carr would record this monumental composition at Royal Studio in Memphis in late 1966.

Jerry Wexler, meanwhile, had been importing Moman and

Tommy Cogbill to Muscle Shoals on a regular basis to work with Wilson Pickett at Fame. When he put in the call to Chips that he was bringing Aretha Franklin down there in February of 1967, Penn was not about to miss out. He began working on another song with Moman expressly for that session,

Do Right Woman-Do Right Man. The song wasn't finished, and Penn recalls using bits and pieces of what Wexler and Aretha said as part of the bridge, before they finally cut a rough version at Fame that night. The rest, as they say, is history, as Wexler took the raw tapes back to New York and pieced together yet another classic Penn-Moman soul masterpiece (for more on all of that, please check out our

Aretha post).

Flush with the success of his Muscle Shoals in NYC Aretha material, Wexler got the idea of doing the same kind of thing with

Solomon Burke. He flew Penn and Moman up to New York (along with Tommy Cogbill,

Spooner Oldham,

Jimmy Johnson, and

Roger Hawkins) to produce a few songs on him in April of 1967. The resulting two-sider,

Take Me (Just As I Am) - (now up on the ol'

A Side, by the way)/

I Stayed Away Too Long (Atlantic 2416) was released immediately prior to our current selection and is, as far as I can tell, the only other record to read 'produced by Chips Moman & Dan Penn'.

This was when Chips told Wexler that he was done traveling, and that if he wanted that 'Memphis Sound' he'd have to come to Memphis. With the sudden interest of his nemesis

Larry Uttal in Moman's studio, Wexler figured he'd better take him up on that quickly, and so sent Esther Phillips down there as the first Atlantic artist to record at American just five days later, on April 15th 1967. Erroneously reported (in my opinion) as a Muscle Shoals session in both the liner notes to

Atlantic Unearthed: Soul Sisters and the

Atlantic Records Discography Project, it features the full 'American Group' along with the fledgling Hi horn section led by

James Mitchell. Although the label credits the song as another Dan Penn-Chips Moman composition, I believe that's in error too, as it had been released originally on Fame by Penn, before he'd even met Chips (the BMI database lists Spooner Oldham as the co-writer). Be that as it may, Esther's just cookin' it up here, man. I love that break, with the bass just kind of melting into that cheesy organ laid over

Reggie Young's surf guitar licks. Very cool.

Although the Solomon Burke record would go to #11 R&B that May, neither side of the Esther Phillips single charted, and that was apparently the end of the Moman-Penn production team (once Penn's own production of

The Letter busted things wide open later that summer, things were never quite the same between them).

Phillips reportedly was having renewed difficulties with heroin addiction at this point, and spent time in what we now call 'rehab'. Upon her release in 1969, she rejoined forces with Leland Rogers for a few singles on the Roulette label, one of which would crack the R&B top forty, before re-signing with Atlantic in 1970. Wexler brought her down to his new digs at Criteria in Miami, and paired her up with the legendary Dixie Flyers.

Their first single together,

Set Me Free, broke into the top forty as well that August, but after three subsequent releases failed to chart, Atlantic (as we've seen with so many other of their soul acts during this same

tres Warner Brothers period) lost interest and let her go. As it turned out, that may have been the best thing that could have happened to her.

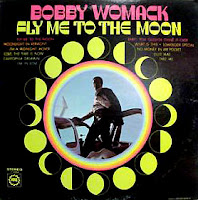

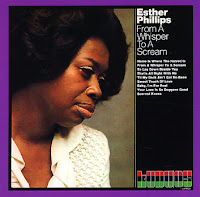

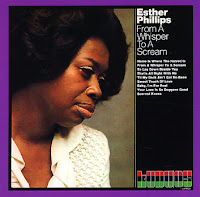

Signed to a contract by Jazz impresario

Creed Taylor in 1972, Esther Phillips was re-invented once again as a sultry and soulfully hip chanteuse who'd been around the block a couple of times. Her amazing first album for Taylor's Kudu subsidiary,

From A Whisper To A Scream, still stands up today, as does the bone-chilling

Gil-Scott Heron composition pulled as the first single from the record,

Home Is Where The Hatred Is. Deep stuff. She would chart a couple of more times for the label in the early seventies, but Disco was coming on strong.

In 1975, Taylor got the idea of pairing Esther with jazz guitarist

Joe Beck. An adept arranger, he took an old swing era number and brought it right to Studio 54.

What A Diff'rence A Day Makes was just a huge hit, and heralded Esther's unique genius to yet another generation. Truly an incredible woman, it's hard to think of anybody else who was able to make that kind of transition as flawlessly as she did. From 78rpm 'race records' to 12" club singles, she had certainly seen it all.

When Kudu folded in the late seventies, Esther signed with Mercury, but nothing much was happening. She would chart one more time with a song called

Turn Me Out on the Winning label in 1983. Sadly, she would die the following year from health issues brought on by her ongoing addiction.

Like

Dinah Washington before her, Esther Phillips bravely faced a life of pain. Pain that is redeemed in the beauty of the work she left behind.

God rest her soul.

I'll Try To Do Better

I'll Try To Do Better