Johnny Jones - No Love As Sweet As Yours (Fury 5053)

No Love As Sweet As Yours

No Love As Sweet As YoursA Not So Happy House

As reported in The New York Times, landmark Harlem record shop Bobby's Happy House was being evicted from its current location effective this past Monday, January 21st. As the 'gentrification' of Manhattan continues it's inexorable crawl northward, it has finally reached 125th Street, long the cultural nexus of Harlem's rich history. The owner of the building that houses Bobby's, something called the Kimco Realty Corporation, couldn't care less. The blistering irony of the fact that they were throwing Bobby Robinson out on the street on Martin Luther King Day was apparently lost on them.

As reported in The New York Times, landmark Harlem record shop Bobby's Happy House was being evicted from its current location effective this past Monday, January 21st. As the 'gentrification' of Manhattan continues it's inexorable crawl northward, it has finally reached 125th Street, long the cultural nexus of Harlem's rich history. The owner of the building that houses Bobby's, something called the Kimco Realty Corporation, couldn't care less. The blistering irony of the fact that they were throwing Bobby Robinson out on the street on Martin Luther King Day was apparently lost on them. I went to the Happy House yesterday to see what the deal was. Robinson's daughter, Denise Benjamin, who's been helping Bobby run the place for years, was kind enough to speak with me. She said that Robinson had been 'in denial' ever since they got the news that they would have to close their doors last summer. "They're going to tear down the building," she told me, "so we've got to move one way or the other." When I mentioned how horrible I thought it was that they were being evicted on MLK Day, she replied "I know, 'I have a dream,' right?" She is currently in negotiations with another landlord around the corner on 125th Street, and is attempting to interest new neighbor Bill Clinton's Economic Empowerment initiative in their plight. So, there is hope. As of right now, however, for the first time in sixty two years Bobby Robinson is not the proprietor of a record store in Harlem.

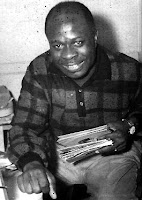

I went to the Happy House yesterday to see what the deal was. Robinson's daughter, Denise Benjamin, who's been helping Bobby run the place for years, was kind enough to speak with me. She said that Robinson had been 'in denial' ever since they got the news that they would have to close their doors last summer. "They're going to tear down the building," she told me, "so we've got to move one way or the other." When I mentioned how horrible I thought it was that they were being evicted on MLK Day, she replied "I know, 'I have a dream,' right?" She is currently in negotiations with another landlord around the corner on 125th Street, and is attempting to interest new neighbor Bill Clinton's Economic Empowerment initiative in their plight. So, there is hope. As of right now, however, for the first time in sixty two years Bobby Robinson is not the proprietor of a record store in Harlem. Denise was still there yesterday because the Kimco slugs came in and inspected the place after they had moved everything out of the store over the weekend, and told them they'd have to clean out the basement (long the repository of unsold store stock), as well. She told them she'd need a little more time. That was the scene I walked into yesterday, as friends and neighbors pitched in to help bring decades of moldering vinyl out into the open for one final 'clearance sale'. There were a couple of crates of 45s there. As I rummaged through them, I couldn't believe that this was how all this history was ending up, that it had ultimately come down to this...

Denise was still there yesterday because the Kimco slugs came in and inspected the place after they had moved everything out of the store over the weekend, and told them they'd have to clean out the basement (long the repository of unsold store stock), as well. She told them she'd need a little more time. That was the scene I walked into yesterday, as friends and neighbors pitched in to help bring decades of moldering vinyl out into the open for one final 'clearance sale'. There were a couple of crates of 45s there. As I rummaged through them, I couldn't believe that this was how all this history was ending up, that it had ultimately come down to this...So much more than merely a 'store owner', Bobby Robinson is a pivotal figure in the evolution of Black American music. This incredible record that I dug out of those crates yesterday is a case in point.

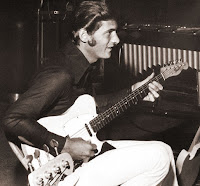

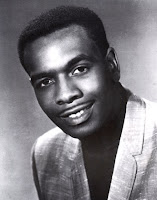

As both a songwriter and producer, Robinson had few equals, as evidenced by this little known 'southern soul' gem, waxed right here in New York. This is not the Nashville guitar playing Johnny Jones (leader of the legendary Imperial Seven and, later on, The King Casuals), but Little Johnny Jones of Augusta, Georgia. Jones, a member of the Swanee Quintet, was chosen to replace Sam Cooke in the Soul Stirrers in 1957. After touring with them that summer, however, he decided that it wasn't for him, and returned home to Georgia (leaving the job open for Johnnie Taylor). Jones went on to record Gospel under his own name for Nashboro's Creed subsidiary but, as far as I can tell, the two singles he cut for Robinson in the late sixties were his only foray into 'secular' music. Just a great singer, you can hear some of his Cooke-styled inflections here... not to mention that little Jackie Wilson like flight there towards the end, whoah! How about those two guitars (one of which is very probably being played by Sterling Magee)? Anyway, just as wonderful records like this one lay unheard all these years in the cellar of the Happy House, so it is that Bobby Robinson has gone virtually unnoticed by the mainstream media.

As both a songwriter and producer, Robinson had few equals, as evidenced by this little known 'southern soul' gem, waxed right here in New York. This is not the Nashville guitar playing Johnny Jones (leader of the legendary Imperial Seven and, later on, The King Casuals), but Little Johnny Jones of Augusta, Georgia. Jones, a member of the Swanee Quintet, was chosen to replace Sam Cooke in the Soul Stirrers in 1957. After touring with them that summer, however, he decided that it wasn't for him, and returned home to Georgia (leaving the job open for Johnnie Taylor). Jones went on to record Gospel under his own name for Nashboro's Creed subsidiary but, as far as I can tell, the two singles he cut for Robinson in the late sixties were his only foray into 'secular' music. Just a great singer, you can hear some of his Cooke-styled inflections here... not to mention that little Jackie Wilson like flight there towards the end, whoah! How about those two guitars (one of which is very probably being played by Sterling Magee)? Anyway, just as wonderful records like this one lay unheard all these years in the cellar of the Happy House, so it is that Bobby Robinson has gone virtually unnoticed by the mainstream media.Below is an appreciation of Mister Robinson that I put up as part of a piece I did last January on Grandmaster Flash:

"Originally from Union, South Carolina, Robinson settled in New York just after World War II. He opened a record store on 125th Street in Harlem, a couple of doors down from the Apollo Theatre, in 1946. Along with his brother Danny, he soon became a fixture in the neighborhood, and was on a first name basis with the performers and music industry types that hung around the Theatre. In the liner notes for the now out-of-print The Fire/Fury Records Story, Bobby goes on to say "I also got to know the fellows who had their own record labels. I remember spending a lot of time with Ahmet Ertegun and his partner, Herb Abramson, when they founded Atlantic Records. They would come up to the store and ask me for advice."

"Originally from Union, South Carolina, Robinson settled in New York just after World War II. He opened a record store on 125th Street in Harlem, a couple of doors down from the Apollo Theatre, in 1946. Along with his brother Danny, he soon became a fixture in the neighborhood, and was on a first name basis with the performers and music industry types that hung around the Theatre. In the liner notes for the now out-of-print The Fire/Fury Records Story, Bobby goes on to say "I also got to know the fellows who had their own record labels. I remember spending a lot of time with Ahmet Ertegun and his partner, Herb Abramson, when they founded Atlantic Records. They would come up to the store and ask me for advice." In What'd I Say, Ertegun (pictured here with Robinson and Clyde McPhatter around 1954) says that he used to give Bobby 25 free copies of their releases if he agreed to play them on his outdoor speakers. As Atlantic's records began flying out of the store, Bobby soon decided to start his own company. Ertegun told him "Listen Bobby, you are making such a mistake. You've done so well out of the record shop, you're going to sink all your money into this ridiculous idea. Please, please don't do it..."

In What'd I Say, Ertegun (pictured here with Robinson and Clyde McPhatter around 1954) says that he used to give Bobby 25 free copies of their releases if he agreed to play them on his outdoor speakers. As Atlantic's records began flying out of the store, Bobby soon decided to start his own company. Ertegun told him "Listen Bobby, you are making such a mistake. You've done so well out of the record shop, you're going to sink all your money into this ridiculous idea. Please, please don't do it..."

Robinson didn't listen, of course, and started up his own Robin label in 1951. That was soon replaced by Red Robin, and a succession of others that were run by Bobby, Danny or both. Local Doo-Wop and Jazz releases on Whirlin' Disc, Holiday, Everlast, Vest and Fling would follow, and the records sold well locally. Bobby longed for national distribution, however, and made a series of bad deals that caused him to close down most of his original labels in 1957.

Robinson didn't listen, of course, and started up his own Robin label in 1951. That was soon replaced by Red Robin, and a succession of others that were run by Bobby, Danny or both. Local Doo-Wop and Jazz releases on Whirlin' Disc, Holiday, Everlast, Vest and Fling would follow, and the records sold well locally. Bobby longed for national distribution, however, and made a series of bad deals that caused him to close down most of his original labels in 1957.He would start up Fury Records (and its accompanying Fire Publishing Company) later that year, and business continued as usual. As we mentioned last month, Bobby hired a young southerner named Marshall Sehorn as his new A&R and promotion man in 1958. It was Sehorn that brought in Wilbert Harrison to record Kansas City at the Bell Sound Studios in New York in March of 1959. The record just took off, going straight to number one on both the R&B and pop charts while selling over 4 million copies (something Ahmet Ertegun had yet to do with Atlantic), and Bobby was on top.

Only it didn't last. Harrison was already under contract to Savoy Records (although he neglected to tell Robinson that) and they sued him for a million dollars. Although they eventually worked it all out, Bobby was unable to release a timely 'follow-up' record on Harrison, and he never charted again. Undaunted, Robinson took the name of his publishing company, and started up a new label at that point so he could continue to record. He would hit the #1 R&B spot again in early 1960 with Georgia transplant Buster Brown's smokin' Fannie Mae (Fire 1008).

He would go on to record classic Blues records by people like Arthur 'Big Boy' Crudup, Sam Meyers, Lightnin' Hopkins and Elmore James (James even cracked the R&B top 20 that year), while making it to #1 once again with the amazing Bobby Marchan's There Is Something On Your Mind. The Savoy lawsuit was finally settled in 1961, and Bobby was able to fire up his Fury label once more. One of the first artists he recorded was a recent high school graduate from Georgia who, along with her brother and two of her cousins, made up Gladys Knight & the Pips.

The great Every Beat Of My Heart had been released on the small Atlanta based Huntom label first, but Bobby flew Gladys and the Pips to New York to re-record it. After the song began to hit, Vee-Jay records in Chicago leased the original master from Huntom, and with their superior distribution network, took it to #1 R&B (the Fury single stalled at #15). Bobby sued this time, and the courts forced Vee-Jay to pay him a nickel for every record they sold. Not bad (the white guy in the above photo is Marshall Sehorn, by the way).

The great Every Beat Of My Heart had been released on the small Atlanta based Huntom label first, but Bobby flew Gladys and the Pips to New York to re-record it. After the song began to hit, Vee-Jay records in Chicago leased the original master from Huntom, and with their superior distribution network, took it to #1 R&B (the Fury single stalled at #15). Bobby sued this time, and the courts forced Vee-Jay to pay him a nickel for every record they sold. Not bad (the white guy in the above photo is Marshall Sehorn, by the way). We've already spoken about the circumstances regarding the label's next #1 R&B smash, Lee Dorsey's Ya-Ya. Sehorn and Robinson's southern connections were paying off big time as the record even broke into the pop top ten. His next big chart successes were to come from closer to home, however. Small's Paradise was a legendary Harlem nightspot located just ten blocks from his record store, and Bobby was a regular. In 1962 he made a bet with the saxophone player in The Noble Knights that he could deliver him a hit.

We've already spoken about the circumstances regarding the label's next #1 R&B smash, Lee Dorsey's Ya-Ya. Sehorn and Robinson's southern connections were paying off big time as the record even broke into the pop top ten. His next big chart successes were to come from closer to home, however. Small's Paradise was a legendary Harlem nightspot located just ten blocks from his record store, and Bobby was a regular. In 1962 he made a bet with the saxophone player in The Noble Knights that he could deliver him a hit. He started a brand new label called Enjoy just for that purpose, and its very first release took King Curtis all the way to #1 R&B with Soul Twist. Curtis had lost the bet, and so had to sign a contract with the new label. The house band at Small's featured Don Gardner on drums and Dee-Dee Ford on keyboards. Bobby heard them singing an incredible song called I Need Your Lovin', and put it out on Fire in the summer of 1962. It coasted to #4, and the follow-up Don't You Worry broke into the top ten as well. Robinson would close out the year with Les Cooper And The Soul Rocker's #12 smash Wiggle Wobble on his Everlast imprint.

He started a brand new label called Enjoy just for that purpose, and its very first release took King Curtis all the way to #1 R&B with Soul Twist. Curtis had lost the bet, and so had to sign a contract with the new label. The house band at Small's featured Don Gardner on drums and Dee-Dee Ford on keyboards. Bobby heard them singing an incredible song called I Need Your Lovin', and put it out on Fire in the summer of 1962. It coasted to #4, and the follow-up Don't You Worry broke into the top ten as well. Robinson would close out the year with Les Cooper And The Soul Rocker's #12 smash Wiggle Wobble on his Everlast imprint.I'm not sure what happened at this point, but Bobby's chart days all but dried up. In Jeff Hannush's great I Hear You Knockin' he says that "By early 1963, Robinson's labels were in financial difficulty. One of Robinson's silent partners, Fats Lewis, pulled out of the operation just as a major deal with ABC was about to consummate."

Whatever the case may be, Robinson kept on keepin' on, continuing to make great records, some of which, in my opinion, are even better than the hits. He had developed into a great producer, and it was said that he had 'the best ear in the business'. Deep soul by the likes of Willie Hightower and Joe Haywood went nowhere, as did cool proto-funk sides by groups like The Ramrods. He remained a much respected figure in Harlem, and often held court backstage at the Apollo. As I've said before, legend has it that he pitched Warm And Tender Love to Jerry Wexler on one such occasion. As near as we can figure it over on soul detective, the last sides he recorded back then were on his new Front Page label circa 1969... [ed. note: I've since found out - yesterday while I was digging through the crates - that this is inaccurate. Bobby was releasing records on a variety of labels right through the seventies.]

That is until he started it all back up again ten years later to record the first wave of Rap as it happened on the streets around him. This is a seminal figure, folks. This is the man that ties it all together... the missing link, if you will. He is still around, working most days at his 'Happy House', which (like we talked about a couple of weeks ago) remains an important cultural focal point in the Harlem community..."

That is until he started it all back up again ten years later to record the first wave of Rap as it happened on the streets around him. This is a seminal figure, folks. This is the man that ties it all together... the missing link, if you will. He is still around, working most days at his 'Happy House', which (like we talked about a couple of weeks ago) remains an important cultural focal point in the Harlem community..."Sadly, as we've seen, this is no longer true.

From Doo-Wop to Hip-Hop, Bobby Robinson has been an integral part of the New York music scene for over sixty years. What will it take to get myopic institutions like The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and (amazingly) The Rhythm & Blues Foundation to sit up and take notice?