Soul Dance Number Three

Soul Dance Number Three

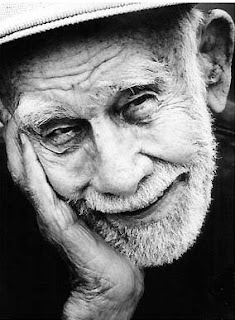

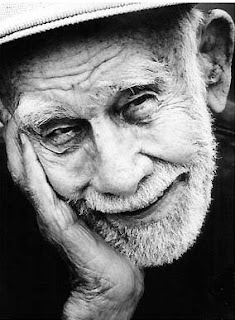

JERRY WEXLER

1917-2008

There was only one.

As the last living link to the glory days at Atlantic Records passes before our eyes, please take a moment with me to reflect on a life well lived. An absolute giant of the 'Soul Era', I don't think you can imagine the music without him. His influence is still felt today, and he remained his wry and lucid self right to the end, providing the top shelf liner notes to

Aretha Franklin - Rare & Unreleased Recordings from the Golden Reign of the Queen of Soul just last year.

Jerry wrote this great song we have here with

Pickett down in Muscle Shoals in 1967. It would break into the R&B top ten that summer. He was proud of that.

Here is an appreciation of Jerry I wrote when he turned 90 in January of 2007:

Wexler grew up in Washington Heights where he developed a fondness for poolrooms, reefer, and Jazz. He and his record collecting pals would scour the city for rare 78s by day, and hang around the clubs by night, listening to the hottest music they could find. They got in on the ground floor of the 52nd Street Bebop explosion, and were usually smoking the same stuff the cats in the band were. It must have been a time! Jerry would often run into

John Hammond out there, the man who had brought

Bessie Smith and

Bille Holiday to Columbia Records. Hammond was all Fifth Avenue money and class, while Wexler, the son of an immigrant window washer, was anything but. He longed for 'the life'... someday, baby, someday.

After a stint in the Army (which he spent stationed in an art deco hotel in Miami Beach), 'Wex' got himself a job writing copy for the newly formed BMI, which led, eventually, to his being hired by

Billboard magazine, the music industry bible. He became a

Brill Building regular, 'working' the offices of all the writers and publishers, while keeping his ear to the ground to pick up what was happening on the streets. In 1949,

Paul Ackerman, editor-in-chief of Billboard's music division, asked his employees to come up with a better term for their 'race records' chart, which was geared towards African-American music. It was Wexler who came up with the term 'Rhythm & Blues'... it stuck.

As we've

discussed before, when Jerry was offered a job at Atlantic Records in 1953, he told

Ahmet Ertegun and

Herb Abramson that he wouldn't work for them unless they sold him an interest in the company. Much to his surprise, they agreed. He dove right in, handling much of the mundane details of running the store ("licking stamps," as he put it), while picking up the nuts and bolts of 'producing' from Ahmet and

Tommy Dowd as they recorded Atlantic 'product' right there in his office. He was a fast learner, and was soon an equal member of the team. Whether composing

Honey Love with

Clyde McPhatter or chiming in with the background vocals on

Big Joe Turner's

Shake Rattle & Roll, he quickly became an integral part of Atlantic's 'sound'.

He began traveling down south with Ertegun, running sessions at Cosimo's studio in New Orleans with legends like

Professor Longhair and

Guitar Slim. Jerry truly loved the city in those days, and prides himself on being one of the few white guys to ever stay at the

Dew Drop Inn. This kind of 'field recording' would continue, with Wexler and Ertegun flying south to record

Brother Ray whenever he was ready. He was there at the Atlanta session that produced

I Got A Woman... imagine?

By the time Herb Abramson got out of the Army in 1955, it was obvious that Wexler had taken his place. It was no coincidence that Atlantic's rise to prominence on the R&B charts had occurred while Jerry was 'working the phones'. Abramson saw the handwriting on the wall, and decided he wanted out. Ahmet's brother

Nesuhi, meanwhile, had worked out a deal with west coast writing and production team

Jerry Lieber and

Mike Stoller to bring them to Atlantic. Closing down their own

Spark label, they brought their unique story-telling style to ATCO, a new subsidiary label that Atlantic had created. They turned operation of ATCO over to Abramson (along with a new kid they had just signed named

Bobby Darin), hoping they could make that arrangement work. After Darin's first few singles tanked, Abramson demanded that they buy him out. Scraping together all the money they could find, Ahmet, Nesuhi, and Jerry did just that, becoming equal partners in the company in 1955.

By 1960, the heyday of Atlantic's R&B roster was just about over. Ray Charles had left for greener pastures at ABC and Bobby Darin (after his run of smash hits like

Mack The Knife and

Beyond The Sea) was on his way out the door. When

Solomon Burke showed up one day out of the clear blue sky, Wexler signed him right then and there. His production of the Country ballad

Just Out Of Reach (Of My Two Open Arms) was absolutely fantastic, going top ten R&B and top 40 pop. The 'Soul Era' at the label had begun.

One of the unsung heroes of the Atlantic saga was a guy named

Joe Galkin. He worked as their southern promotion man, driving around in a constant flurry of activity from one radio station to another, bestowing gifts and pearls of wisdom amidst the clouds of cigarette smoke and banlon shirts. He called Wexler regularly with updates on what was hot and what was not down south. It was Galkin who hipped Jerry to

Jim Stewart's fledgling

Sattelite Records label (soon to become

STAX), and got them their infamous Atlantic distribution deal. It was Joe Galkin who had started a label with

Otis Redding (Jotis), and was instrumental in recording

These Arms Of Mine at the tail end of a

Johnny Jenkins session at STAX. It was Galkin who handed

Rick Hall the phone one day, so he could tell Jerry about

When A Man Loves A Woman. Suffice it to say that Wexler valued his opinions highly, and loved him for the character that he was.

Jerry was astonished by the southern style of recording that used 'head arrangements' and wasn't bound by charges for studio time. When he brought

Wilson Pickett down to STAX in 1965, they were just as amazed with his hands on production style, and it was reportedly his demonstrating the 'Jerk' that put the beat of

In The Midnight Hour squarely 'on the one', and helped create the studio's trademark sound. After Wexler brought

Don Covay down there to wax

See-Saw later that year, Jim Stewart apparently felt that Atlantic was trying to take over, and barred them from recording there again. Although he'd probably never admit it, I think Wexler was heartbroken at that point. According to Tom Dowd, "They were sweet, beautiful people, the folks in Memphis, and they'd be the first to say they learned as much from Wexler as he learned from them. Jerry would be demanding; he made them less laid back..."

Joe Galkin got Jerry hooked up with Rick Hall at FAME at that point, and he brought Pickett down to Muscle Shoals in the summer of 1966. To the young kids in Hall's rhythm section, Wexler (now almost 50) was like this mythic musical figure, and they were essentially scared to death. Wexler had brought

Tommy Cogbill and

Chips Moman with him from Memphis, and once the sessions got going things were just fine. Once again, his production was 'hands on', coming out from behind the board to coach the players and make sure he got what he wanted. It was Wexler's idea for Pickett to sing those "1, 2, 3s" at the beginning of

Land Of 1000 Dances, very cool.

We've

already talked about what happened when Jerry brought

Aretha down to Fame in early 1967... Finding himself shut out of yet another southern studio, he brought the musicians to New York and finished production on the first of fourteen albums he would make with her. That incredible record,

I Never Loved A Man (The Way That I Love You), was so important on so many levels. Wexler had shown his old hero John Hammond what Aretha was capable of (something Hammond had been unable to find at Columbia), while cementing his relationship with the Muscle Shoals crowd (telling them to give him a call if they ever wanted to go out on their own), and forging a new sound with the help of his in-house production team of Tom Dowd and

Arif Mardin. "What Tommy was to engineering, Arif was to arranging, the super pro. What's more," Jerry said, "the two could easily switch roles. No producer has ever enjoyed better backup. they freed me up to direct, concentrate on the groove..."

I think it says a lot that when Otis Redding died in December of 1967, it was Jerry Wexler that was asked to eulogize him at his funeral in Macon. Unable to control his emotion, Wexler spoke of Otis' "love and tremendous faith in human possibilities... a man whose composition

Respect has become an anthem of hope for people everywhere." A heavy moment.

Seeking to continue the sucess he'd been having recording down south, Wexler had loaned some money to Chips Moman to upgrade the equipment at his American Sound Studio in Memphis. In the summer of 1968, he hatched a plan to bring Atlantic's latest acquisition, British pop superstar

Dusty Springfield, down there to record. Springfield had come up as a 'folkie' in the early sixties, before being captivated by American soul music. Her career took off with hits like

Wishin' And Hopin' and

You Don't Have To Say You Love Me keeping her high in the charts on both sides of the Atlantic. Touring in those days, she became fast friends with

Martha Reeves (performing as a

Vandella from time to time), and introduced the British public to Motown as a host on the popular TV series

Ready, Steady, Go. When her contract with Philips was up, she decided to sign with her idol Aretha Franklin's label in America.

Wexler did his homework, and prepared a list of about 100 songs for Dusty to consider for the album. She didn't like any of them. He wasn't sure what to make of that, but he hung in there, and after "months of agonizing evaluations" they were able to settle on eleven tunes. One of those songs,

Son Of A Preacher Man, had been slated for Aretha initially, but she turned it down. "All Jerry did was talk about Aretha, and I was frankly intimidated," Dusty later said,"If there's one thing that inhibits good singing it's fear. I covered the fear by being in pain. I drove Jerry crazy."

"Tom Dowd wrote the horn parts for

Son Of A Preacher Man on the plane on the way down to Memphis, and they're f#@*ing brilliant!," says Wexler. Oh yes, they are. With the 'Memphis Boys' and

The Sweet Inspirations rarin' to go, Jerry, Tom and Arif were all set to produce this killer album. Only Dusty wasn't. She was so overcome by her fears that she refused to sing a note while they were down there at American. "I became paralysed by the ghosts of the studio!," she said, "I knew I could sing the songs well enough, but it brought pangs of insecurity. . . that I didn't deserve to be there." She ended up screaming at Dowd, calling him a 'prima-donna'. "The only prima-donna here, Madamoiselle Springfield, is you," Wexler retorted.

They returned to New York and began the excruciating task of capturing Springfield's vocals over many takes and re-takes (Don't get me wrong, I'm not trashing Dusty here, far from it... I think the final result stands as one of the truly great albums in Atlantic's long history, and is a testimony to the talent and hard work of everyone involved).

Son Of A Preacher Man was released as a single first, and quickly reached the top ten in December of 1968. When the album was released in January, for whatever reason, it didn't sell. Undaunted, Wexler released

Don't Forget About Me and

Breakfast in Bed as a two-sider over the course of March and April, but they barely made it into the Hot 100...

While Wexler was making his move into southern soul, Ahmet Ertegun had moved his base of operations out to L.A., picking up some of the pieces left behind by Sam Cooke's ill-fated 'soul stations' in the process. He scooped up

Harold Battiste and the rest of the expatriate New Orleans crowd and was using them as arrangers and studio musicians on ATCO. He also signed a young couple that had been hanging around Battiste and

Phil Spector,

Sonny & Cher. Their first single for the label,

I Got You Babe (produced and arranged by Battiste), went straight to #1 in the summer of 1965. Ertegun became a fixture of the scene out there, and started his move into what would come to be known as 'rock', signing groups like

Buffalo Springfield and

Iron Butterfly.

Wexler had grown close with

Barry Beckett, Jimmy Johnson, David Hood and Roger Hawkins over the years, and considered them almost like a second family. When they finally came to him in 1969 saying they were ready to leave Rick Hall and Fame behind, Jerry was ecstatic. He gladly loaned them the money to set up shop in an old casket factory located at 3614 Jackson Highway in Muscle Shoals, and promised them beaucoup business from Atlantic. The first album recorded there, oddly enough, was by Cher. Considered somewhat of a

cult classic, it was re-issued as part of

Rhino's 'handmade CD' series a few years back.

In an oft-repeated story, Wexler heard

Mac Rebennack playing his Professor Longhair style of piano one night during a break at the studio, and turned on the tape machine. He had no idea of Mac's incredible R&B roots, and he was just blown away. He sent copies of the resulting tape out to his friends. The music brought him back to those days down at Cosimo's almost twenty years before, and he convinced Mac to lose the whole 'night tripper' persona and record the great

Dr. John's Gumbo album in 1972. Although it didn't sell (of course), Wexler still considers it one of the best things he's ever produced.

Another of his favorites is the incredible

Doug Sahm and Band, which was recorded in New York in October of 1972. Wexler has described Sahm as "the best musician I ever knew, because of his versatility, and the range of his information and taste." He surrounded him with great musicians (and

Bob Dylan) and produced an all-time classic. It didn't sell either. This was around the same time that Jerry conceived the idea of establishing himself as the king of 'Atlantic South', setting himself up at

Criteria Studios in Miami.

It had been Jerry's idea to sell Atlantic to Warner Brothers back in 1967. Fearing the fate most of the other R&B indies had suffered, he reasoned that they should sell while they were at the top of their game. Warner ended up paying only about half of what the company was worth, and although they had guaranteed that all three partners would continue to conduct business as usual, Wexler just couldn't abide the 'corporate types', and he let them know it. As people like

David Geffen began to insinuate themselves further and further into the company, Wexler grew more and more apoplectic, becoming persona non gratis at Board meetings and company functions. By removing himself to Miami, he had done them all a favor. The records he produced weren't selling, they continued to remind him, as they successfully marginalized his work. Perhaps the last straw came when Jerry decided to open a country division in Nashville, and produce

two great albums on

Willie Nelson that flopped. Finally, both sides had had enough, and in an emotional meeting in Ahmet Ertegun's office in 1975, Wexler basically painted himself into a corner. There was no way he could continue on as merely an employee, he said. It was time to go.

Jerry soldiered on as a freelance producer, and would win a Grammy for bringing another of John Hammond's discoveries, Bob Dylan, down to Muscle Shoals to record

Slow Train Coming in 1979. "If there was any constant in my life, it was Muscle Shoals," Jerry said, "...maybe because the people in Muscle Shoals were both friends and admirers. Maybe because Muscle Shoals made me feel the way I'd felt when I first arrived there back in the sixties - like a participant in the music, a member of the rhythm section... I fell into a groove of comfort."

The music Wexler's been a part of has stood the test of time, as has he. In a recent interview he said "Everybody seems to be coming to my door; BBC, NPR... well, there aren't too many people at the age of 90 that are coherent or even alive!"

He never compromised his vision, ever.

We should all thank him for that.

Bless Your Heart

Bless Your Heart "John R was a good man... an all the way good man." That's what Lattimore told me. Anyone else I've ever spoken with who knew him has said the same thing. This was a straight shooter, an honest man who treated his artists fairly, and expected the same in return. As we've seen, he was willing to 'go to the wall' to get the sound he wanted, driving to Memphis on a regular basis to record with the best in the business. After five years of his association with Fred Foster and Monument Records, his J.R. Enterprises had leased over 75 singles to Sound Stage 7.

"John R was a good man... an all the way good man." That's what Lattimore told me. Anyone else I've ever spoken with who knew him has said the same thing. This was a straight shooter, an honest man who treated his artists fairly, and expected the same in return. As we've seen, he was willing to 'go to the wall' to get the sound he wanted, driving to Memphis on a regular basis to record with the best in the business. After five years of his association with Fred Foster and Monument Records, his J.R. Enterprises had leased over 75 singles to Sound Stage 7. Shut out of Memphis once again, John was determined to try and create his own 'house band' right there in Nashville. He worked out a deal with Scotty Moore, who had recently opened his own Music City studio on 19th Avenue South, and set about making that happen. Continuing to use our man Bob Wilson as the session leader, he put together the band he would come to call 'The Music City Four', which would include top shelf musicians like Kenny Buttrey, Mac Gayden and Tim Drummond.

Shut out of Memphis once again, John was determined to try and create his own 'house band' right there in Nashville. He worked out a deal with Scotty Moore, who had recently opened his own Music City studio on 19th Avenue South, and set about making that happen. Continuing to use our man Bob Wilson as the session leader, he put together the band he would come to call 'The Music City Four', which would include top shelf musicians like Kenny Buttrey, Mac Gayden and Tim Drummond. It was Wayne Moss' bass line on a song written by Monument's Harlan Howard that paved the way for all of this, and proved to Fred Foster that it was possible to pull it off. Richbourg had been recording Joe Simon at American in Memphis, and had also done some sessions with him at Fame in Muscle Shoals (resulting in one of our fave B Sides), but none of those records could touch the phenomenal success of The Chokin' Kind. When John R played the master for Fred Foster he told him "I think you need to remix it. The bass is way too hot."

It was Wayne Moss' bass line on a song written by Monument's Harlan Howard that paved the way for all of this, and proved to Fred Foster that it was possible to pull it off. Richbourg had been recording Joe Simon at American in Memphis, and had also done some sessions with him at Fame in Muscle Shoals (resulting in one of our fave B Sides), but none of those records could touch the phenomenal success of The Chokin' Kind. When John R played the master for Fred Foster he told him "I think you need to remix it. The bass is way too hot." John asked him to trust him on this one, and released it the way it was. The record would spend over three months on the charts, including three weeks at number one R&B. Fred, of course, had been wrong, and he was ecstatic about it. The label had never seen that kind of success before and it kind of changed everything. Foster, for whatever reason, didn't seem as interested in leasing as much material from J.R. Enterprises as it had in the past, and decided to concentrate on Simon, hoping for a repeat performance. By mid 1969, Roscoe Shelton, Sam Baker and Sir Lattimore Brown were all gone, and in addition to Simon, Richbourg's Sound Stage 7 releases were new Nashville productions on folks like Ella Washington, Jackey Beavers and Moody Scott.

John asked him to trust him on this one, and released it the way it was. The record would spend over three months on the charts, including three weeks at number one R&B. Fred, of course, had been wrong, and he was ecstatic about it. The label had never seen that kind of success before and it kind of changed everything. Foster, for whatever reason, didn't seem as interested in leasing as much material from J.R. Enterprises as it had in the past, and decided to concentrate on Simon, hoping for a repeat performance. By mid 1969, Roscoe Shelton, Sam Baker and Sir Lattimore Brown were all gone, and in addition to Simon, Richbourg's Sound Stage 7 releases were new Nashville productions on folks like Ella Washington, Jackey Beavers and Moody Scott. John R started up two of his own labels at this point, called Sound Plus and Seventy 7, which were apparently created to serve as an outlet for the stuff that Monument wasn't interested in. Although he would release some truly great 45s on a roster of artists that would come to include Willie Hobbs, Earl Gaines, and Ann Sexton (among others), the records weren't selling, and without the big company behind him, there wasn't much of a budget for promotion.

John R started up two of his own labels at this point, called Sound Plus and Seventy 7, which were apparently created to serve as an outlet for the stuff that Monument wasn't interested in. Although he would release some truly great 45s on a roster of artists that would come to include Willie Hobbs, Earl Gaines, and Ann Sexton (among others), the records weren't selling, and without the big company behind him, there wasn't much of a budget for promotion. He would form yet another (albeit short-lived) label named Luna somewhere around in here, and helped to bail out his partner Allen Orange's own floundering House Of Orange imprint by signing Geater Davis. Moving Davis over to Seventy 7 eventually, he managed to break into the R&B charts for the label. Orange became his full-time promotion man. There are those who say that this was a mistake. What little money Richbourg had soon began drying up, and he found it difficult to pay for studio time.

He would form yet another (albeit short-lived) label named Luna somewhere around in here, and helped to bail out his partner Allen Orange's own floundering House Of Orange imprint by signing Geater Davis. Moving Davis over to Seventy 7 eventually, he managed to break into the R&B charts for the label. Orange became his full-time promotion man. There are those who say that this was a mistake. What little money Richbourg had soon began drying up, and he found it difficult to pay for studio time. Turning to the mountain of material he had 'in the can', John R began releasing Lattimore Brown records once again. J.R. Enterprises had retained the rights to all of the masters they had recorded for Sound Stage 7, and re-released some of that material (sometimes on both labels at once!), in order to keep up a steady supply of 'product'.

Turning to the mountain of material he had 'in the can', John R began releasing Lattimore Brown records once again. J.R. Enterprises had retained the rights to all of the masters they had recorded for Sound Stage 7, and re-released some of that material (sometimes on both labels at once!), in order to keep up a steady supply of 'product'. He would go so far as to release an LP called 'This Is Lattimore's World', which was composed entirely of stuff that had been previously recorded. Lattimore told me that he never knew the album existed, and had never even seen a copy. Of the twelve tracks on the record, seven had been released on Sound Stage 7, and three more had been issued as singles on Seventy 7. These singles, like the awesome number you're listening to now, represent some of Lattimore's best material.

He would go so far as to release an LP called 'This Is Lattimore's World', which was composed entirely of stuff that had been previously recorded. Lattimore told me that he never knew the album existed, and had never even seen a copy. Of the twelve tracks on the record, seven had been released on Sound Stage 7, and three more had been issued as singles on Seventy 7. These singles, like the awesome number you're listening to now, represent some of Lattimore's best material. Try as I may, I have been unable to determine where and when these records were cut (except for the flip of our current selection, Don't Trust No One, which, as we've seen was recorded at Stax). Songs like So Says My Heart and It Hurts Me So Bad (which was an LP only track) are just fantastic, and I find it hard to believe that Fred Foster passed on them. For that matter, I don't understand why Lattimore was let go, based on the quality of this material. When I asked him, he just kind of shrugged. There is some bogus story about how his 'lack of focus' in the studio irked Richbourg, but I don't believe that... especially in light of those awesome Renegade cuts he did with Chuck Chellman almost immediately after he was given his walking papers.

Try as I may, I have been unable to determine where and when these records were cut (except for the flip of our current selection, Don't Trust No One, which, as we've seen was recorded at Stax). Songs like So Says My Heart and It Hurts Me So Bad (which was an LP only track) are just fantastic, and I find it hard to believe that Fred Foster passed on them. For that matter, I don't understand why Lattimore was let go, based on the quality of this material. When I asked him, he just kind of shrugged. There is some bogus story about how his 'lack of focus' in the studio irked Richbourg, but I don't believe that... especially in light of those awesome Renegade cuts he did with Chuck Chellman almost immediately after he was given his walking papers. As I was getting ready for this post, I noticed that this wonderful song we have here was co-wriiten by Lattimore and 'C.Curry'. C. Curry had also been the composer on one of the LP only tracks, Boo Ga Lou Sue. This had to be Clifford Curry, I figured. I was able to track Clifford down through his manager, Joe Meador, and spent a delightful hour on the phone with him. He's remained active in the business, and continues to make 'shag' records for the beach music crowd, even though he lives in Nashville. Like most everybody else, he thought Lattimore was dead, and he couldn't believe we had found his long lost friend. He told me that he met Brown when he came into Knoxville to play a gig at Harper's V.I.P. Lounge, and that he liked the town so much he decided to stay.

As I was getting ready for this post, I noticed that this wonderful song we have here was co-wriiten by Lattimore and 'C.Curry'. C. Curry had also been the composer on one of the LP only tracks, Boo Ga Lou Sue. This had to be Clifford Curry, I figured. I was able to track Clifford down through his manager, Joe Meador, and spent a delightful hour on the phone with him. He's remained active in the business, and continues to make 'shag' records for the beach music crowd, even though he lives in Nashville. Like most everybody else, he thought Lattimore was dead, and he couldn't believe we had found his long lost friend. He told me that he met Brown when he came into Knoxville to play a gig at Harper's V.I.P. Lounge, and that he liked the town so much he decided to stay. The two became fast friends, and hung out together all the time. Curry, who wrote most of his own material, recorded demos of his songs with a piano player named Winfred Doggett on a little Wollensack tape recorder that he had. Lattimore liked two of the songs, and brought them to John R in Nashville. Clifford never heard another word about them, he said, and didn't know if they had ever been released, or even recorded, until now. This was all news to him... incredible.

The two became fast friends, and hung out together all the time. Curry, who wrote most of his own material, recorded demos of his songs with a piano player named Winfred Doggett on a little Wollensack tape recorder that he had. Lattimore liked two of the songs, and brought them to John R in Nashville. Clifford never heard another word about them, he said, and didn't know if they had ever been released, or even recorded, until now. This was all news to him... incredible. Just as he had done in Dallas, Lattimore opened up a club in Knoxville and re-activated his booking agency, using the connections he had made through his many years in the business to bring in top name acts. He had gotten married, and he and his wife ran the place, calling it The Silver Slipper. When she died following open heart surgery to correct a congenital valve defect, it laid him low, he told me. He closed the place down and walked away from the music business altogether... at least temporarily.

Just as he had done in Dallas, Lattimore opened up a club in Knoxville and re-activated his booking agency, using the connections he had made through his many years in the business to bring in top name acts. He had gotten married, and he and his wife ran the place, calling it The Silver Slipper. When she died following open heart surgery to correct a congenital valve defect, it laid him low, he told me. He closed the place down and walked away from the music business altogether... at least temporarily. OK, I've put together a podcast of some of the records we've been talking about here that haven't been posted so far. It starts out with Lattimore's other two Renegade sides, then goes back to some Zil, Duchess, Sound Stage 7 and Seventy Seven material. I've also included those Roscoe Shelton and Sam Baker sides that were cut at Stax, as well as the ones that were arranged by Dan Penn at American Sound, among a few other things. As always, you can listen to it over there in the sidebar, or check it out here.

OK, I've put together a podcast of some of the records we've been talking about here that haven't been posted so far. It starts out with Lattimore's other two Renegade sides, then goes back to some Zil, Duchess, Sound Stage 7 and Seventy Seven material. I've also included those Roscoe Shelton and Sam Baker sides that were cut at Stax, as well as the ones that were arranged by Dan Penn at American Sound, among a few other things. As always, you can listen to it over there in the sidebar, or check it out here.