You Really Know How To Hurt A Guy (You Really Know How To Make Him Cry)PART ONE

Once in a great while, a CD comes along that changes everything... that somehow gets under your skin and makes you wonder how you ever lived without it.

The Best of Jimmy Hughes is like that. Long considered the 'holy grail' of Southern Soul, the music that

Rick Hall produced down in Muscle Shoals for his

FAME label had never been re-issued on CD. As

we reported back in November of 2006, a historic agreement with EMI was about to change all that. Complete with a magnificent re-mastering job by Rick's son

Rodney (at the same landmark studio where it was cut in the first place), and over two hours of interviews in an enhanced package, this collection of Jimmy's groundbreaking recordings represents the first release from that legendary catalogue.

It kicks ass.

Thanks to the folks at

Shore Fire Media, I was able to speak with Jimmy on the phone this past Monday about all of this, and he is simply elated that people are discovering his music all over again. Let's take a closer look...

As we've

discussed in the past, Rick Hall played bass in a 'frat circuit' group called

The Fairlanes, along with a sax player named

Billy Sherrill, and a musical genius of a guitar player named

Terry Thompson. Working the same territory was a band called

The Pallbearers that was led by a brash young kid named

Dan Penn. Holed up in a room over the drug store in the small town of Florence, Alabama (with another local character named

Tom Stafford), they'd listen to R&B, write songs, and fantasize about making records of their own.

Rick Hall, never much of a dreamer, set out on his own to make that happen. He borrowed some money and converted an old tobacco warehouse out on the Wilson Dam Road into a studio of sorts. When a local guy that worked in the town's movie theater showed a song he had written to Stafford, he brought him out to see Rick. He would record

Arthur Alexander's

You Better Move On and a song Terry Thompson had written,

A Shot Of Rhythm And Blues, using members of both The Fairlanes and the Pallbearers as the back-up band in the summer of 1961.

It was there in that place that the 'Muscle Shoals Sound' was born.

Thanks to a sympathetic Nashville dee-jay named

Noel Ball, the record was picked up by

Randy Wood's Dot label, and spent three months in the Billboard Hot 100, climbing as high as number 24 in early 1962 (on its way to becoming one of the most influential two-siders ever recorded). The guys down in Florence couldn't believe it. This felt like the big time. Suddenly a star, Alexander used the royalties he got to buy himself a brand new Lincoln, and make sure he was seen driving it all around town.

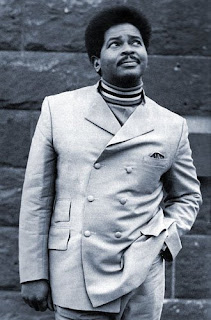

Jimmy Hughes

Jimmy Hughes was working at a place called E.S. Robins Floor Products across the river in Muscle Shoals. He had been singing lead in a quartet-style Gospel group called

The Singing Clouds since his senior year in high school back in his hometown of Leighton, five years before. He was good, and he knew it. He saw Arthur behind the wheel of that Lincoln, and thought, 'Hey, why not me?'. A fellow member of the Clouds named

Carl Bailey worked at a car lot that was owned by Rick Hall's father-in-law (Bailey would go on to become a well known radio personality in the region, eventually becoming the owner of station WOWL), and it was Bailey who got Hall and Jimmy together out at the studio on Wilson Dam Road.

In his upcoming autobiography

Hell Bent For FAME (as told to

Terry Pace), Rick recalls meeting Jimmy for the first time, "I was awestruck by his chiseled movie-star good looks and mesmerized by the power of his high tenor voice." Hall decided to cut a song on him that he had written with WLAY dee-jay

Quin Ivy and, on the strength of his success with Arthur Alexander, was able to lease it to the

Guyden label up in Philadelphia in late 1962. Although it did well locally,

I'm Qualified never managed to dent the charts. Jimmy 'kept his day job' at Robins, but began singing R&B on the weekends... he had 'crossed-over'.

"Why don't you try your hand at writing something?" Rick told him and, after spending a couple of weeks working on it during the late shift at Robins, Jimmy came back with a song so good, it would basically create the whole concept of 'Southern Soul', only at that point Rick didn't quite get it. They recorded a demo of the song, and it got put on the back burner.

Rick, meanwhile, took the money he had made off of 'You Better Move On', and used it to design and build a new studio at 603 East Avalon Avenue in Muscle Shoals, which opened its doors in the Spring of 1964. Along with Terry Thompson,

David Briggs,

Norbert Putnam and

Jerry Carrigan (who were now the nucleus of the first 'rhythm section'), Jimmy Hughes became the first person to ever record there, putting the finishing touches on the song he had written two years earlier,

Steal Away. According to Rick, "Jimmy simply reared back, dug in, and with passion and determination written all over his face, HE NAILED IT!!! 'What a singer,' I thought, 'What a singer! What a star!!'"

Finally convinced of what Dan Penn had been telling him all along, that

Steal Away had the potential to be a big hit, he began shopping it around to record companies, without any luck. Atlanta impresario

Bill Lowery, who had brought

The Tams down there to record, was the one who convinced Hall to start his own label, and release the song himself. Just as he had done with the studio, he named the label after the publishing company they had started back in the drugstore days, Florence Alabama Music Enterprises, better known as

FAME.

He pressed up 1000 copies of the 45, packed them into a Ford Fairlane wagon he borrowed from his Father-In-Law's lot (along with two cases of vodka and Dan Penn) and set off on a mission to get

Steal Away the attention it deserved. They knocked on the door of 'every R&B station that had a tower' in the South, covering hundreds of miles over the course of a couple of weeks. Rick, a "white cracker" as he described himself, would tell them "I ain't much, I ain't got nothin'... but I'm begging, please play my record. Listen to it, and if you like, it play it..." and so they did. By the time he and Dan got back, the phones were ringing off the hook at the distributors all up and down the line, clamoring for copies of that first Fame single.

Steal Away, as Jimmy himself said, was "what Black people liked" and was one of the first records to focus on that whole 'how can something so right be so wrong?' thang that is still resonating in Southern Soul today.

Jimmy, meanwhile, had no idea what Rick and Dan were up to, and was as surprised as anyone to hear his song being played on the radio. He took two weeks vacation from Robins, and went out in support of the record. He was amazed by the response he was getting and, at the end of the two weeks, he signed on with Bill Lowery, who booked him all over the South. He never looked back. Faced with ever increasing demand, Rick signed a distribution deal with

Vee-Jay Records through their southern representative,

Mac Davis. This song of songs would spend the whole summer of 1964 on the charts, and put Muscle Shoals, and Jimmy Hughes, on the map.

They began work on a

Steal Away LP that would be released on Vee-Jay in 1964 (VJ 1102). The singles from the album still appeared on FAME, and Jimmy's version of

Try Me would make it to #65 R&B that Fall. Perhaps the most notable thing about that 45, however, was its B side,

Lovely Ladies, which was one of the first collaborations between Dan Penn and the new keyboard man at the studio,

Lindon 'Spooner' Oldham. Jimmy continued to write himself, and

It Was Nice was cut as the B side of his next record, but it didn't do much.

The Loving Physician

The Loving Physician, another Hughes composition (later covered by

Ted Taylor), was released as the flip of our current cool selection. Another early Penn/Oldham number, they just don't come much better than this. They say that Dan and Spooner would hole up at the studio for days at a time writing these timeless songs. Imagine? If you listen closely, I'm pretty sure that's Penn on the background vocals. Very cool. Amazingly, though, once again, the record didn't chart (perhaps even more amazingly, it didn't make the CD!).

Despite their quality, neither of Jimmy's next two records,

Midnight Affair and

Everybody Let's Dance, would make the charts either. The main reason for that, I think, was FAME's distribution deal with Vee-Jay. By mid 1965, the company was collapsing under its own weight, and was involved in lawsuits involving everyone from The Four Seasons to The Beatles. Once the premier black-owned R&B label in the world, their move from Chicago to L.A. had been the beginning of the end. Caught up in their own difficulties, promoting Rick Hall's singles just wasn't that high on their to-do list. By August of 1966 the company was out of business.

As luck would have it, this was also about the same time that

Joe Galkin, the Southern promo man for Atlantic Records, started knocking on the door. Joe handed the phone to Rick Hall one day, and he told

Jerry Wexler about this guaranteed #1 hit that Jimmy's cousin had just cut with his old pal Quin Ivy. It was this part that he played in convincing Atlantic to pick up

When A Man Loves A Woman that helped get Rick his new distribution deal with ATCO. He brought in

Ray Stevens, and they cut a new 'funked-up' version of

Neighbor, Neighbor (now up on

The A Side), a

Huey Meaux song that Jimmy had already recorded for the Vee-Jay LP. With the muscle of the big company behind it, it just took off, climbing all the way to #4 R&B at the same time that cousin Percy's big record was riding the #1 spot in May of 1966. Jimmy and Percy had gone to the same high school in Leighton, and here they were both in the top five. Wow.

With the 'second rhythm section' now firmly in place, Fame was just burning it up on all cylinders. Jimmy's follow-up record was another incredible Penn/Oldham number,

I Worship The Ground You Walk On, which would hit the R&B top 25 at the same time that

Wilson Pickett's Fame recorded

Land of 1000 Dances (on which Jimmy told me he sang those high

Na-Na-Na-Na-Nas) was in the top slot. Incredible stuff. A Country songwriter named

Jimmy Gilreath had been hanging around the studio for a while, and Hughes heard him working on a tune up front in the lobby. "What you gonna do with that song?" he asked him. "You want it, you can have it," Gllreath said. Jimmy's favorite of all the songs he recorded,

Why Not Tonight is one of the all time great 'Black Country' songs which would, once again, crack the top five in early 1967. It was also just a huge record overseas and, according to our friend

Ben the Balladeer, it was heard more than the national anthem in

Suriname in those days. Jimmy was still writing himself, and the B side of that record, the phenomenal

I'm A Man Of Action, is one of his best.

Jimmy was there when Atlantic brought down

Aretha, when

Otis Redding cut

Arthur Conley, when Chess brought

Etta James. His own take on

Don't Lose Your Good Thing (the Rick Hall/Spooner Oldham/Bob Killen classic) was released next and although it didn't chart, it still holds up as the best version, in my opinion. Another Hughes composition,

Time Will Bring You Back, was released as the flip of a rocking cover of

Hi-Heel Sneakers which missed the charts as well. Most of his work from this period was collected on the

Why Not Tonight LP (ATCO 33-209) issued in late 1967.

This was around the same time that Jimmy, like most everyone else that worked the Southern chitlin' circuit back then, signed on with

Red-Wal, the Macon based management and booking agency started up by Otis Redding and

Phil and

Alan Walden. They were involved in the big Stax-Volt package tour of Europe that year, and were instrumental in getting Arthur Conley on the bill. They represented

Johnny Taylor,

Eddie Floyd,

Sam and Dave... "You should sign with Stax," they told him, "that's where it's all happening!" "Besides," they said, "we're all distributed by Atlantic anyway, right?" Just one big happy family. Eventually he was convinced, and Alan Walden brought Jimmy to Memphis to sign a deal with them.

Otis Redding's plane went down on December 10, 1967.

Atlantic, meanwhile, had made the decision to move Jimmy (along with

Clarence Carter) up to the big label. On January 20, 1968, they released one of the best songs Jimmy had ever written,

It Ain't What You Got (Atlantic 2454), a record which would put him right back on the R&B charts. On February 3rd, Atlantic was sold to Warner Brothers, which would set in motion the severing of their relationship with Stax. Shortly after this, Jimmy told me, he found himself sitting next to Jerry Wexler on a plane. "You know that we're no longer going to be distributing Stax, right?" he asked him. Jimmy was floored. He had no idea.

continued in PART TWO...

Just Ain't Strong As I Used To Be (You Done Fed Me Sumpin')

Just Ain't Strong As I Used To Be (You Done Fed Me Sumpin') When Jimmy Hughes got to Stax in early 1968, it was a company in transition. As we discussed in part one, he had signed with them after Alan Walden convinced him it would be a good career move, shortly before Walden's partner Otis Redding was killed in that fateful plane crash in December of 1967. On April 4, 1968, Doctor Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, a place that had figured prominently in the history of Stax and their association with Atlantic Records. Songs like Knock On Wood and In The Midnight Hour had been composed there. Now it was all over. On May 16th, the distribution deal with Atlantic officially ended, and all the masters that Stax had recorded up to that point became the property of the New York company, which itself was now a wholly owned subsidiary of Warner Brothers. On the heels of losing their biggest star, they had just lost their entire back catalogue. This is the Stax that Jimmy Hughes walked into on East McLemore Avenue back then.

When Jimmy Hughes got to Stax in early 1968, it was a company in transition. As we discussed in part one, he had signed with them after Alan Walden convinced him it would be a good career move, shortly before Walden's partner Otis Redding was killed in that fateful plane crash in December of 1967. On April 4, 1968, Doctor Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, a place that had figured prominently in the history of Stax and their association with Atlantic Records. Songs like Knock On Wood and In The Midnight Hour had been composed there. Now it was all over. On May 16th, the distribution deal with Atlantic officially ended, and all the masters that Stax had recorded up to that point became the property of the New York company, which itself was now a wholly owned subsidiary of Warner Brothers. On the heels of losing their biggest star, they had just lost their entire back catalogue. This is the Stax that Jimmy Hughes walked into on East McLemore Avenue back then.

Rather than shrink from the task, Stax guru Al Bell, who had helped build the label into the soul powerhouse it had become, viewed all of this as an opportunity for a new beginning. He was instrumental in negotiating the sale of the company to Gulf + Western on May 29th, thereby creating an immediate influx of cash to help promote their product. Complete with the brand new 'snapping fingers' logo, singles by Eddie Floyd, Booker T. & The M.G.'s and Judy Clay & William Bell were all over the radio that summer.

Jimmy told me he felt like the 'low man on the totem pole' at this point, and was unsure of how he would make it in his new surroundings. At FAME, he had pretty much been the star of the show, and now he was just a face in the crowd. They placed him on Volt, the subsidiary label that had been home to all of Otis Redding's hits. According to Rob Bowman, in the excellent liner notes to The Complete Stax/Volt Soul Singles, Vol 2: 1968-1971, it was Jim Stewart who decided to have Jimmy cover the Motown written I Like Everything About You (inexplicably left off the great Soulsville Sings Hitsville) as his first release. Produced by M.G.'s drummer Al Jackson Jr, it just missed the R&B top 20 in September of 1968.

That would be the last Jimmy Hughes record to ever hit the charts.

Rather than shrink from the task, Stax guru Al Bell, who had helped build the label into the soul powerhouse it had become, viewed all of this as an opportunity for a new beginning. He was instrumental in negotiating the sale of the company to Gulf + Western on May 29th, thereby creating an immediate influx of cash to help promote their product. Complete with the brand new 'snapping fingers' logo, singles by Eddie Floyd, Booker T. & The M.G.'s and Judy Clay & William Bell were all over the radio that summer.

Jimmy told me he felt like the 'low man on the totem pole' at this point, and was unsure of how he would make it in his new surroundings. At FAME, he had pretty much been the star of the show, and now he was just a face in the crowd. They placed him on Volt, the subsidiary label that had been home to all of Otis Redding's hits. According to Rob Bowman, in the excellent liner notes to The Complete Stax/Volt Soul Singles, Vol 2: 1968-1971, it was Jim Stewart who decided to have Jimmy cover the Motown written I Like Everything About You (inexplicably left off the great Soulsville Sings Hitsville) as his first release. Produced by M.G.'s drummer Al Jackson Jr, it just missed the R&B top 20 in September of 1968.

That would be the last Jimmy Hughes record to ever hit the charts.

Within a couple of weeks, Johnnie Taylor's monster Who's Making Love, would solidify Stax' position as a force to be reckoned with, and validate Al Bell's vision for the future of the company. Maybe that's why Jimmy's next single didn't do much. Written by Isaac Hayes, David Porter and Homer Banks (and once again produced by Al Jackson), the great Let 'Em Down, Baby (Volt 4008) harkens back to the old days at the label, and may not have been promoted much for just that reason. Bell had brought in producer Don Davis from Detroit and, after the unqualified success he had with Johnnie Taylor, there was some serious friction between the old and the new. At this point, Bell took Jimmy into his own hands, and produced the obviously Davis-influenced Chains Of Love (Volt 4017). It didn't make much noise, probably because it just wasn't that good.

Within a couple of weeks, Johnnie Taylor's monster Who's Making Love, would solidify Stax' position as a force to be reckoned with, and validate Al Bell's vision for the future of the company. Maybe that's why Jimmy's next single didn't do much. Written by Isaac Hayes, David Porter and Homer Banks (and once again produced by Al Jackson), the great Let 'Em Down, Baby (Volt 4008) harkens back to the old days at the label, and may not have been promoted much for just that reason. Bell had brought in producer Don Davis from Detroit and, after the unqualified success he had with Johnnie Taylor, there was some serious friction between the old and the new. At this point, Bell took Jimmy into his own hands, and produced the obviously Davis-influenced Chains Of Love (Volt 4017). It didn't make much noise, probably because it just wasn't that good.

In 1969, Al Bell hatched a scheme that would provide the label with a much-needed 'catalogue' and establish it as an 'album company' at the same time. His plan to release twenty eight LPs (and thirty singles) on the same date that May was perceived by many to be overkill (Jerry Wexler called it "regional nuthead business... a panic move"). Be that as it may, Something Special, the Jimmy Hughes entry into the LP sweepstakes, has been called "one of the finest soul records of 1969." In addition to both sides of the three singles he had already released, new material for the album was cut across town at the Sam Phillips' Recording Service.

In 1969, Al Bell hatched a scheme that would provide the label with a much-needed 'catalogue' and establish it as an 'album company' at the same time. His plan to release twenty eight LPs (and thirty singles) on the same date that May was perceived by many to be overkill (Jerry Wexler called it "regional nuthead business... a panic move"). Be that as it may, Something Special, the Jimmy Hughes entry into the LP sweepstakes, has been called "one of the finest soul records of 1969." In addition to both sides of the three singles he had already released, new material for the album was cut across town at the Sam Phillips' Recording Service.

The producer of those sessions was Charles Chalmers. Chalmers had made a name for himself as a 'go-to' sax man in both Memphis and Muscle Shoals, blowing amazing solos on scores of hit records, including some of Jimmy's Fame material (he had been the sax player on Willie Mitchell's hit version of Soul Serenade just the year before). His skills as an arranger and producer were also well known in town, after the work he had done with former Stax artists Barbara & The Browns, not to mention the records he cut with the likes of Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin, and Etta James. He married an acoustic guitar player and singer named Donna Rhodes, and a song they wrote together would be released as the single from the album. The infectious I'm So Glad, cool electric sitar and all, should definitely have been a hit, but was 'lost in the sauce' of all those concurrent releases, I guess. It was one of the first records to feature the background vocals of Charlie, Donna and her sister Sandy, the trio that would later become known as Rhodes, Chalmers & Rhodes.

It truly amazes me sometimes how all of this stuff interconnects.

The producer of those sessions was Charles Chalmers. Chalmers had made a name for himself as a 'go-to' sax man in both Memphis and Muscle Shoals, blowing amazing solos on scores of hit records, including some of Jimmy's Fame material (he had been the sax player on Willie Mitchell's hit version of Soul Serenade just the year before). His skills as an arranger and producer were also well known in town, after the work he had done with former Stax artists Barbara & The Browns, not to mention the records he cut with the likes of Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin, and Etta James. He married an acoustic guitar player and singer named Donna Rhodes, and a song they wrote together would be released as the single from the album. The infectious I'm So Glad, cool electric sitar and all, should definitely have been a hit, but was 'lost in the sauce' of all those concurrent releases, I guess. It was one of the first records to feature the background vocals of Charlie, Donna and her sister Sandy, the trio that would later become known as Rhodes, Chalmers & Rhodes.

It truly amazes me sometimes how all of this stuff interconnects.

I spoke with Howard Grimes last week to try and get a little background on what happened next. Howard had been the original drummer at Satellite Records (before it was called Stax), and recalls those days working with Chips Moman fondly. He cut Gee Whiz with Carla Thomas at the 'Hi Studio' (Royal) in 1960, after Chips was unhappy with the original version they had recorded around the corner at Satellite. Little did he know it was to become a second home to him down the line. Grimes played on groundbreaking records like William Bell's You Don't Miss Your Water, and was the drummer for Moman's Triumphs, the precursors to the M.G.'s. According to Howard, he missed a phone call for a session one day, and that pretty much changed everything.

I spoke with Howard Grimes last week to try and get a little background on what happened next. Howard had been the original drummer at Satellite Records (before it was called Stax), and recalls those days working with Chips Moman fondly. He cut Gee Whiz with Carla Thomas at the 'Hi Studio' (Royal) in 1960, after Chips was unhappy with the original version they had recorded around the corner at Satellite. Little did he know it was to become a second home to him down the line. Grimes played on groundbreaking records like William Bell's You Don't Miss Your Water, and was the drummer for Moman's Triumphs, the precursors to the M.G.'s. According to Howard, he missed a phone call for a session one day, and that pretty much changed everything.

Al Jackson, Jr, who was the drummer in Willie Mitchell's band, got the call instead and he laid down the beat on what would become the first Booker T. & The M.G.'s record and propel Stax to the next level in 1962. After the ensuing blow-up between Moman and Jim Stewart, Howard was seen, I imagine, as one of 'Chips' boys', and the phone stopped ringing. He went off on a tour with a local band called Flash & The Board Of Directors, and when he got back he auditioned for the spot that Al's departure to Stax had opened up in Willie's band. He got the job.

Al Jackson, Jr, who was the drummer in Willie Mitchell's band, got the call instead and he laid down the beat on what would become the first Booker T. & The M.G.'s record and propel Stax to the next level in 1962. After the ensuing blow-up between Moman and Jim Stewart, Howard was seen, I imagine, as one of 'Chips' boys', and the phone stopped ringing. He went off on a tour with a local band called Flash & The Board Of Directors, and when he got back he auditioned for the spot that Al's departure to Stax had opened up in Willie's band. He got the job.

Howard credits Willie with teaching him how to 'hold back' and says he learned how to set the time by watching his foot on the bandstand. "If Willie's foot was moving, I'd know I got it right, but if he was standing still, I knew there was something wrong." After a while he got it down, and it was Willie who gave him his nickname, 'the Bulldog' because once he "locked that pocket, ain't nobody can shake him off." He was joined in that outfit by the three young Hodges brothers from out in Germantown who, along with Willie's brother James and his stepson Archie, made up the band in those days. Touring in support of Soul Serenade in early 1968, they were involved in a horrific accident out in Kansas, which convinced Willie to stay closer to home. When he became a partner in Hi Records the following year, his tight road band would officially become the label's new rhythm section. After Hi Records founder Joe Cuoghi died in 1970, Mitchell made some renovations to the studio that helped with the acoustics, and by early 1971, he had created 'the sound' that would sell millions upon millions of records over the next few years.

Howard credits Willie with teaching him how to 'hold back' and says he learned how to set the time by watching his foot on the bandstand. "If Willie's foot was moving, I'd know I got it right, but if he was standing still, I knew there was something wrong." After a while he got it down, and it was Willie who gave him his nickname, 'the Bulldog' because once he "locked that pocket, ain't nobody can shake him off." He was joined in that outfit by the three young Hodges brothers from out in Germantown who, along with Willie's brother James and his stepson Archie, made up the band in those days. Touring in support of Soul Serenade in early 1968, they were involved in a horrific accident out in Kansas, which convinced Willie to stay closer to home. When he became a partner in Hi Records the following year, his tight road band would officially become the label's new rhythm section. After Hi Records founder Joe Cuoghi died in 1970, Mitchell made some renovations to the studio that helped with the acoustics, and by early 1971, he had created 'the sound' that would sell millions upon millions of records over the next few years.

Al Jackson, meanwhile, had stayed close with Mitchell, and knew all about what was happening over there on South Lauderdale. He had written a song with Jimmy Hughes, and Stax gave him the green light to go ahead and produce it over at Willie's studio, resulting in this incredible record we have here today. A Stax single that was recorded at Hi... now how cool is that?? The Hodges brothers are really burning it up on this one, with Teenie's killer guitar, Charles' smokin' Hammond, and Leroy's hypnotic bass line laid over The Bulldog's untouchable beat... wow! I really can't say enough about how much I love this 45... that's the Memphis Horns (Wayne Jackson and Andrew Love) blowing those hot lines, and Jimmy's impassioned high energy delivery makes this just top of the line stuff. Jimmy has said that he thought Hi Rhythm was the best studio band out there in those days. "You could just feel it some kind of way. They were soulful guys. It makes you want to sing. Look like it go through your body" he told Rob Bowman. Without a doubt the best of his Volt releases, it would also be his last.

Why? I asked him.

Al Jackson, meanwhile, had stayed close with Mitchell, and knew all about what was happening over there on South Lauderdale. He had written a song with Jimmy Hughes, and Stax gave him the green light to go ahead and produce it over at Willie's studio, resulting in this incredible record we have here today. A Stax single that was recorded at Hi... now how cool is that?? The Hodges brothers are really burning it up on this one, with Teenie's killer guitar, Charles' smokin' Hammond, and Leroy's hypnotic bass line laid over The Bulldog's untouchable beat... wow! I really can't say enough about how much I love this 45... that's the Memphis Horns (Wayne Jackson and Andrew Love) blowing those hot lines, and Jimmy's impassioned high energy delivery makes this just top of the line stuff. Jimmy has said that he thought Hi Rhythm was the best studio band out there in those days. "You could just feel it some kind of way. They were soulful guys. It makes you want to sing. Look like it go through your body" he told Rob Bowman. Without a doubt the best of his Volt releases, it would also be his last.

Why? I asked him.

He said that no matter what he did, he just couldn't seem to "climb the ladder" at Stax. With so many other artists who were there before him, he was frustrated by what he saw as a lack of promotion. He also told me that, as his producer, "Al Jackson wanted to sort of change me, and it just wasn't there... I couldn't go over to that style." Although he remained under contract until 1973, Jimmy decided instead to go back to school, and got himself a steady job with the Federal Government, one from which he has just recently retired. He has no regrets about his career, and although he is thrilled to have his music back in the public eye, he told me he has no plans to start performing again. There is talk, however, that he will be at the second annual Ponderosa Stomp Music Conference... that would really be something, wouldn't it?

He said that no matter what he did, he just couldn't seem to "climb the ladder" at Stax. With so many other artists who were there before him, he was frustrated by what he saw as a lack of promotion. He also told me that, as his producer, "Al Jackson wanted to sort of change me, and it just wasn't there... I couldn't go over to that style." Although he remained under contract until 1973, Jimmy decided instead to go back to school, and got himself a steady job with the Federal Government, one from which he has just recently retired. He has no regrets about his career, and although he is thrilled to have his music back in the public eye, he told me he has no plans to start performing again. There is talk, however, that he will be at the second annual Ponderosa Stomp Music Conference... that would really be something, wouldn't it?

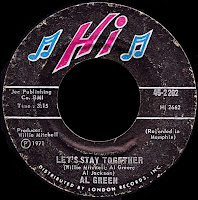

Al Jackson, meanwhile, repaid Willie for the use of his studio by co-writing and playing drums on Al Green's #1 smash Let's Stay Together (which, of course, also featured Rhodes, Chalmers & Rhodes on the background vocals) just a few months after this record came out (for more on all of that, head on over to The A Side).

Life is funny sometimes.

Al Jackson, meanwhile, repaid Willie for the use of his studio by co-writing and playing drums on Al Green's #1 smash Let's Stay Together (which, of course, also featured Rhodes, Chalmers & Rhodes on the background vocals) just a few months after this record came out (for more on all of that, head on over to The A Side).

Life is funny sometimes.