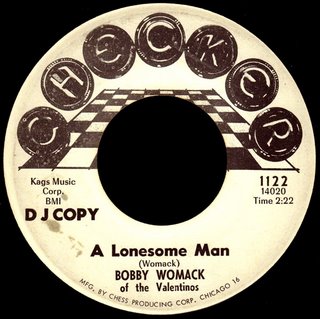

Bobby Womack of the Valentinos - A Lonesome Man (Checker 1122)

A Lonesome Man

Part One Of The Story - first posted in 2006

Friendly Womack sang Gospel with his brothers down in the coal mining country of West Virginia. They called themselves The Womack Brothers, and Friendly promised the Lord that if he sent him five sons, he would see to it that they would carry on the tradition and sing Gospel under that name. He moved to Cleveland, got work in a steel mill, and before long his prayers had been answered.

Friendly's new group, The Voices Of Love, would rehearse up at the Womack house, and his boys would listen in, doing imitations of the various members later on that kept them in stitches. The middle brother, Bobby, began sneaking around and playing his father's guitar while he was at work. Left handed, he had to figure out his own method, with the strings "upside down". (He still plays that way today...)

Friendly's new group, The Voices Of Love, would rehearse up at the Womack house, and his boys would listen in, doing imitations of the various members later on that kept them in stitches. The middle brother, Bobby, began sneaking around and playing his father's guitar while he was at work. Left handed, he had to figure out his own method, with the strings "upside down". (He still plays that way today...)By the early fifties, Friendly was keeping his promise, and had his boys singing Gospel at churches around the area. In 1953, he asked S.R. Crain, a senior member of The Soul Stirrers, if they could open up for them at a program held at Cleveland's Friendship Baptist Church. He was in the process of telling them to "stick to Sunday School", when Sam Cooke overheard and pushed Crain to let them do it. The Womack Brothers were a big hit, and Sam made sure that the congregation forked over some "quiet money" to the family to help them with expenses. The $73 they collected seemed like a million bucks to 9 year old Bobby, and, from that moment on, he wanted to be "just like Sam Cooke".

The Brothers career took off from there, and they began traveling the "Gospel Highway", working with groups like The Staple Singers and The Five Blind Boys Of Mississippi. The Blind Boys were impressed with young Bobby's guitar work, and took him on the road with them. When their fabled lead singer Archie Brownlee died of pneumonia in 1960, he was replaced by the great Roscoe Robinson. It was Robinson who believed in the potential of the Womack boys, and called old friend Sam Cooke.

The Brothers career took off from there, and they began traveling the "Gospel Highway", working with groups like The Staple Singers and The Five Blind Boys Of Mississippi. The Blind Boys were impressed with young Bobby's guitar work, and took him on the road with them. When their fabled lead singer Archie Brownlee died of pneumonia in 1960, he was replaced by the great Roscoe Robinson. It was Robinson who believed in the potential of the Womack boys, and called old friend Sam Cooke. Cooke, who had just started up his own SAR label, was in the market for young talent and agreed to meet the brothers in Detroit. Sam was pushing them to 'cross-over' as he had done, but the Womacks, fearing the wrath of the Father (both the one up in Heaven, and their own back in Cleveland), were reluctant to do so. He made a deal with them; "Okay, fellas, we'll cut you all a Gospel record. But if it don't hit, will you all cut me a pop?" The deal was done, and The Womack Brothers' first single Somebody's Wrong, was released on SAR in 1961.

Cooke, who had just started up his own SAR label, was in the market for young talent and agreed to meet the brothers in Detroit. Sam was pushing them to 'cross-over' as he had done, but the Womacks, fearing the wrath of the Father (both the one up in Heaven, and their own back in Cleveland), were reluctant to do so. He made a deal with them; "Okay, fellas, we'll cut you all a Gospel record. But if it don't hit, will you all cut me a pop?" The deal was done, and The Womack Brothers' first single Somebody's Wrong, was released on SAR in 1961.It flopped. Now it was their turn to make good on a promise. J.W. Alexander, Sam's partner at SAR, changed their name to The Valentinos and they re-worked the lyrics to a Gospel song Bobby had written for their first session (Couldn't Hear Nobody Pray) and came up with the great Lookin' For A Love. It sold two million copies in the summer of 1962, and spent over 3 months on the charts, cracking the top ten R&B and even breaking into the Billboard Hot 100. Friendly wanted no part in any of this, of course, and was just as glad to see his boys take off for California in the car Sam paid for, than to hear them sing 'the devil's music' in his own home.

It was Sam who saw something in Bobby, and made him the lead singer in place of his brother Curtis. "Curtis sings pretty like me." he said, " But now Bobby, he sings with authority. When Bobby sings he demands attention." Cooke sent the Valentinos out on tour with James Brown to school them in the ways of the R&B road, and when they came back all starched, pressed and walking in unison, he knew their 'basic training' had been a success. Sam next took Bobby out with him as a guitar player in his own band (much to his brothers' chagrin), and, in many ways, made him his "protegé". He chose to let Bobby ride in the limo with him (while everyone else in the band was back in the station wagon), and they talked for hours while America rolled on by. Bobby always had his guitar on hand, and Sam, it is said, got quite a few song ideas by listening to him play (when Womack confronted him with this, Sam said, "Okay, I'm taking your shit, but I'm doing you better than James Brown would... "). Suffice it to say that both men got something they needed from the other.

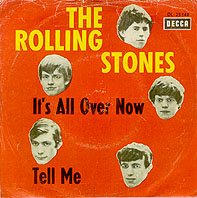

It was Sam who saw something in Bobby, and made him the lead singer in place of his brother Curtis. "Curtis sings pretty like me." he said, " But now Bobby, he sings with authority. When Bobby sings he demands attention." Cooke sent the Valentinos out on tour with James Brown to school them in the ways of the R&B road, and when they came back all starched, pressed and walking in unison, he knew their 'basic training' had been a success. Sam next took Bobby out with him as a guitar player in his own band (much to his brothers' chagrin), and, in many ways, made him his "protegé". He chose to let Bobby ride in the limo with him (while everyone else in the band was back in the station wagon), and they talked for hours while America rolled on by. Bobby always had his guitar on hand, and Sam, it is said, got quite a few song ideas by listening to him play (when Womack confronted him with this, Sam said, "Okay, I'm taking your shit, but I'm doing you better than James Brown would... "). Suffice it to say that both men got something they needed from the other. In June of 1964, J.W. Alexander was pulling out all the stops to promote the new Valentinos single, It's All Over Now. Radio stations all over the country were flooded with advance promo copies of the rockin' shout out record with the 'hook' that just couldn't miss (Bobby had written it after hearing his uncle Wes say that about his Aunt Betty about a thousand times). The Rolling Stones heard it in New York while they were in the studio for an interview with Murray The K (aka 'the fifth Beatle'). Their manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, contacted Sam about performing rights, and they recorded the song within a week at the Chess Studios in Chicago. Their record company (Decca/London) got into the act and "rush-released" the single, putting it out on both sides of the big pond the day before the Valentinos' version was officially released. Can you imagine these guys?

In June of 1964, J.W. Alexander was pulling out all the stops to promote the new Valentinos single, It's All Over Now. Radio stations all over the country were flooded with advance promo copies of the rockin' shout out record with the 'hook' that just couldn't miss (Bobby had written it after hearing his uncle Wes say that about his Aunt Betty about a thousand times). The Rolling Stones heard it in New York while they were in the studio for an interview with Murray The K (aka 'the fifth Beatle'). Their manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, contacted Sam about performing rights, and they recorded the song within a week at the Chess Studios in Chicago. Their record company (Decca/London) got into the act and "rush-released" the single, putting it out on both sides of the big pond the day before the Valentinos' version was officially released. Can you imagine these guys?It was the Stones' breakthrough record, becoming their first number one hit in the UK, and rising to #26 here in the US. The Valentinos' original didn't stand a chance, spending only two weeks on the charts and stalling at #94 R&B. When they found out Sam had okayed the licensing of the song, they couldn't believe it. "What do I need this Pat Boone shit for?" Bobby said, "Let them get their own songs. They mean nothing to me!" Cooke, always the visionary, tried to explain to them that this was the way things were headed in the the music industry, and that they'd be a "part of history". Although it took him quite a while to get there, Bobby finally admiited "...he was right, man. He was always in the future."

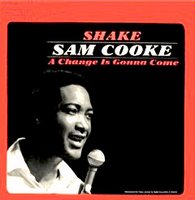

When Sam Cooke wrote A Change Is Gonna Come in late 1963, it scared him. After he had gone into the studio and recorded it, with René Hall's great big arrangement and everything, he called up Bobby. "Come on over, I want you to hear something", he said. He played the song for him on his huge movie theatre speakers, there in the dark. Sam 'looked right through him'... "what do you think, Bobby?", he asked. "It sounds like death... it's just so eerie. It gives me the chills, Sam." Cooke said he had to agree, and told him "I promise I won't ever release that song... not while I'm alive."

When Sam Cooke wrote A Change Is Gonna Come in late 1963, it scared him. After he had gone into the studio and recorded it, with René Hall's great big arrangement and everything, he called up Bobby. "Come on over, I want you to hear something", he said. He played the song for him on his huge movie theatre speakers, there in the dark. Sam 'looked right through him'... "what do you think, Bobby?", he asked. "It sounds like death... it's just so eerie. It gives me the chills, Sam." Cooke said he had to agree, and told him "I promise I won't ever release that song... not while I'm alive."When Sam was shot to death On December 11, 1964, Bobby's world was torn apart. He remembered his reaction to the song, how he had told Sam a second time, "It sounds like death, like somebody died or somebody is going to die"... RCA released A Change Is Gonna Come on December 22nd, as the B side of Shake.

On March 5th 1965, Bobby Womack married Sam Cooke's widow, Barbara Campbell at the Los Angeles County Court House (they had been turned away two weeks before because he had not yet turned 21). Whether Barbara was motivated by love, a need for support or some kind of revenge, we'll probably never know. Bobby has said that he married her to protect Sam's family, and to keep Barbara from "doing something crazy". In any event, the record-buying public (as well as Sam's family in Chicago) viewed it as too much too soon. They saw Campbell as a shameless woman who had no respect for their idol, and Womack as a little gold digger who could never fill Sam's shoes. The papers ate it up.

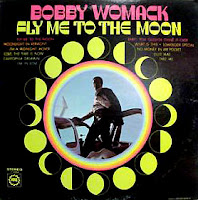

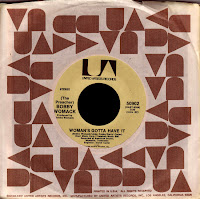

On March 5th 1965, Bobby Womack married Sam Cooke's widow, Barbara Campbell at the Los Angeles County Court House (they had been turned away two weeks before because he had not yet turned 21). Whether Barbara was motivated by love, a need for support or some kind of revenge, we'll probably never know. Bobby has said that he married her to protect Sam's family, and to keep Barbara from "doing something crazy". In any event, the record-buying public (as well as Sam's family in Chicago) viewed it as too much too soon. They saw Campbell as a shameless woman who had no respect for their idol, and Womack as a little gold digger who could never fill Sam's shoes. The papers ate it up.As SAR began to disintegrate around them, the Valentinos signed with Chess Records, but nothing much was happening. Today's selection is the B side of Bobby's first single under his own name, and was released on their Checker subsidiary in 1965 (it's the flip of I Found A True Love, the original version of the tune Wilson Pickett would take to #11 in 1968). They couldn't give the record away. As Bobby has said, at this point disk jockeys were "throwing his records in the garbage", as nobody wanted to hear them. I personally think this is a great song, and shows what a pro Womack had become during his years with Sam. Although it may be a little over-produced (there's no production credits on the label, so I'm not sure by whom), it still cranks along with Bobby's guitar holding down the bottom. I love the vocals, which definitely show Cooke's influence (how could they not)? When he belts out there towards the end that "don't nobody seem to want ol' Bob", it sounds like a wry commentary on what was going down at the time...

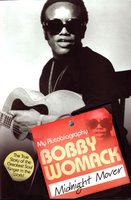

We'll pick up the rest of The Womack's unreal story in some future post, but meanwhile let me recommend his recently released autobiography Midnight Mover: The True Story of the Greatest Soul Singer in the World (modest, he's not) as well as the encyclopedic (and indispensable) Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke by our man in the street, Peter Guralnick.

We'll pick up the rest of The Womack's unreal story in some future post, but meanwhile let me recommend his recently released autobiography Midnight Mover: The True Story of the Greatest Soul Singer in the World (modest, he's not) as well as the encyclopedic (and indispensable) Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke by our man in the street, Peter Guralnick.Great stuff.

(to be continued...)