Chris Kenner - I Like It Like That, Part 2 (Instant 3229)

I Like It Like That, Part 2

I Like It Like That, Part 2AN INSTANT OF TOUSSAINT

As you know, I'm a huge Allen Toussaint fan. Like Professor Longhair before him, his creative genius has taken New Orleans music to the next level again and again over the course of the last fifty years. He was the subject of my very first post, and I've gone so far as to call him the patron saint of The B Side, as I don't believe there's anybody out there who's produced more incredible 'flips' than he has. Yes, his name pops up all the time on these pages (just try entering it in the red kelly search thing), as he does on those of my compadres Dan Phillips and Larry Grogan, who share my passion for the man's music.

As you know, I'm a huge Allen Toussaint fan. Like Professor Longhair before him, his creative genius has taken New Orleans music to the next level again and again over the course of the last fifty years. He was the subject of my very first post, and I've gone so far as to call him the patron saint of The B Side, as I don't believe there's anybody out there who's produced more incredible 'flips' than he has. Yes, his name pops up all the time on these pages (just try entering it in the red kelly search thing), as he does on those of my compadres Dan Phillips and Larry Grogan, who share my passion for the man's music. We've talked about how he was hired by a record distributor named Joe Banashak after he auditioned along with his partner Allen Orange in January of 1960. Banashak and his partner, WYLD dee-jay Larry McKinley, had started up their own Minit label and Toussaint became their in-house composer and producer. From Jessie Hill to Ernie K.Doe, Benny Spellman, Aaron Neville and Irma Thomas, the timeless records he cut for the company will live on forever.

We've talked about how he was hired by a record distributor named Joe Banashak after he auditioned along with his partner Allen Orange in January of 1960. Banashak and his partner, WYLD dee-jay Larry McKinley, had started up their own Minit label and Toussaint became their in-house composer and producer. From Jessie Hill to Ernie K.Doe, Benny Spellman, Aaron Neville and Irma Thomas, the timeless records he cut for the company will live on forever. As will much of the the later work he did with his new partner Marshall Sehorn both on Amy and their own legendary Sansu and Deesu labels. A lot of that music is just beginning to be fully appreciated, thanks to Sundazed re-issues like Get Low Down! and Looking For My Baby, and is just absolutely top shelf stuff. Rather than try and summarize Allen's long and varied career, I want to focus on one area of it that has, for the most part, been overlooked.

As will much of the the later work he did with his new partner Marshall Sehorn both on Amy and their own legendary Sansu and Deesu labels. A lot of that music is just beginning to be fully appreciated, thanks to Sundazed re-issues like Get Low Down! and Looking For My Baby, and is just absolutely top shelf stuff. Rather than try and summarize Allen's long and varied career, I want to focus on one area of it that has, for the most part, been overlooked. In 1961, Joe Banashak helped New Orleans record store owner Irving Smith open up another label called 'Valiant'. Larry McKinley was again brought in as a partner, but their first couple of releases didn't do much. Smith and McKinley (who was soon forced out of the record business as a result of the federal 'payola' investigations) both agreed to let Banashak 'run things', and he in turn gave full artistic license to Toussaint. He was forced to change the name of the label after a west coast outfit named Valiant threatened to sue, and it became 'Instant'.

In 1961, Joe Banashak helped New Orleans record store owner Irving Smith open up another label called 'Valiant'. Larry McKinley was again brought in as a partner, but their first couple of releases didn't do much. Smith and McKinley (who was soon forced out of the record business as a result of the federal 'payola' investigations) both agreed to let Banashak 'run things', and he in turn gave full artistic license to Toussaint. He was forced to change the name of the label after a west coast outfit named Valiant threatened to sue, and it became 'Instant'. By the time you read this, I'll be on my way to New Orleans, and so (as always) I wanted to leave you with a little 'lagniappe' to hold you over till I get back. I've put together a new episode of the podcast that is a selective chronological look at this early formative period at Instant, from its inception in 1961 until Toussaint was drafted into the army in 1963. I call it AN INSTANT OF TOUSSAINT. Now, let's take a closer look...

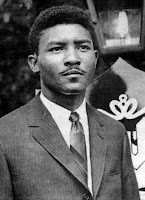

By the time you read this, I'll be on my way to New Orleans, and so (as always) I wanted to leave you with a little 'lagniappe' to hold you over till I get back. I've put together a new episode of the podcast that is a selective chronological look at this early formative period at Instant, from its inception in 1961 until Toussaint was drafted into the army in 1963. I call it AN INSTANT OF TOUSSAINT. Now, let's take a closer look... The first release on the label (which was initially pressed on Valiant) was by the one and only Chris Kenner. Kenner (nicknamed 'Bear') was a hard-drinking longshoreman who pretty much kept to himself. He also happened to be a brilliant songwriter. In 1957 he came to Dave Bartholomew at Imperial with a song he had written that was so good he signed him on the spot. Sick And Tired climbed to #13 R&B that summer, and to #14 when Fats Domino covered it the following year (not to mention the great Elton Anderson version of a few years later). Notoriously drunk and unable to remember the words he had written, he soon ran afoul of Lew Chudd, Bartholomew's boss, and he was let go after the follow-up single failed to chart.

The first release on the label (which was initially pressed on Valiant) was by the one and only Chris Kenner. Kenner (nicknamed 'Bear') was a hard-drinking longshoreman who pretty much kept to himself. He also happened to be a brilliant songwriter. In 1957 he came to Dave Bartholomew at Imperial with a song he had written that was so good he signed him on the spot. Sick And Tired climbed to #13 R&B that summer, and to #14 when Fats Domino covered it the following year (not to mention the great Elton Anderson version of a few years later). Notoriously drunk and unable to remember the words he had written, he soon ran afoul of Lew Chudd, Bartholomew's boss, and he was let go after the follow-up single failed to chart. Chudd was also the national distributor for Minit, and so when Chris came knocking on Banashak's door he had to turn him away. That is until Smith came up with the proposal for the new label. Kenner brought his latest song idea to Toussaint, and together they worked it up into the phenomenal I Like It Like That, Part 1. Much to Chudd's dismay, the record took off, and would spend over 4 months on the charts in 1961, making it to #2 both R&B and Pop (topped only by Mother In Law, which Ernie K-Doe took all the way to #1 for Minit during the same time frame). In addition to Toussaint's amazing piano, this cool instrumental workout we have here on Part 2 features James Rivers on the saxophone and shows how adept Allen was as an arranger, and why he's featured as a co-writer here on the flip. Great stuff.

Chudd was also the national distributor for Minit, and so when Chris came knocking on Banashak's door he had to turn him away. That is until Smith came up with the proposal for the new label. Kenner brought his latest song idea to Toussaint, and together they worked it up into the phenomenal I Like It Like That, Part 1. Much to Chudd's dismay, the record took off, and would spend over 4 months on the charts in 1961, making it to #2 both R&B and Pop (topped only by Mother In Law, which Ernie K-Doe took all the way to #1 for Minit during the same time frame). In addition to Toussaint's amazing piano, this cool instrumental workout we have here on Part 2 features James Rivers on the saxophone and shows how adept Allen was as an arranger, and why he's featured as a co-writer here on the flip. Great stuff. Kenner was apparently kind of intimidated by Toussaint, who was pretty much his exact opposite. He showed up for his sessions clean and sober, and was willing to work with Allen until they got it right. After the follow-up record didn't sell, Banashak was scratching his head over the fact that he couldn't keep copies of Something You Got on the shelves. It was Ernie K. Doe and Benny Spellman who told him that all the kids in the Ninth Ward were buying it because they could dance the Popeye to it. There is still (and probably always will be) some debate as to who had the first 'Popeye Record', but this one sure is a contender, and Allen Toussaint deserves more credit as the man who nurtured that sailor man beat. Although you hear Alvin Robinson's 1964 version a lot more often, Kenner's original is still worth checking out (we'll talk more about The Popeye when I return).

Kenner was apparently kind of intimidated by Toussaint, who was pretty much his exact opposite. He showed up for his sessions clean and sober, and was willing to work with Allen until they got it right. After the follow-up record didn't sell, Banashak was scratching his head over the fact that he couldn't keep copies of Something You Got on the shelves. It was Ernie K. Doe and Benny Spellman who told him that all the kids in the Ninth Ward were buying it because they could dance the Popeye to it. There is still (and probably always will be) some debate as to who had the first 'Popeye Record', but this one sure is a contender, and Allen Toussaint deserves more credit as the man who nurtured that sailor man beat. Although you hear Alvin Robinson's 1964 version a lot more often, Kenner's original is still worth checking out (we'll talk more about The Popeye when I return). Probably the most well known of Kenner's compositions, though, is the fabled Land Of 1000 Dances. Based loosely on a Gospel song Chris used to sing in his early days (Children Go Where I Send Thee), it didn't do much when it was first released in 1962, but Atlantic got behind it a year later and it cruised to #77 on the Hot 100 in the summer of 1963. Probably one of the most covered songs of all time, they just don't come much better than this, y'all. Toussaint did a couple more singles on him before he got drafted, and Kenner would return to the label off and on to be produced by Sax Kari and Eddie Bo, but his charting days were over. They say that he drank up or gave away his considerable royalty checks as fast as they arrived, and he sadly pulled a three year stretch in Angola starting in 1968. After that, things were never the same. He died of a heart attack in 1976.

Probably the most well known of Kenner's compositions, though, is the fabled Land Of 1000 Dances. Based loosely on a Gospel song Chris used to sing in his early days (Children Go Where I Send Thee), it didn't do much when it was first released in 1962, but Atlantic got behind it a year later and it cruised to #77 on the Hot 100 in the summer of 1963. Probably one of the most covered songs of all time, they just don't come much better than this, y'all. Toussaint did a couple more singles on him before he got drafted, and Kenner would return to the label off and on to be produced by Sax Kari and Eddie Bo, but his charting days were over. They say that he drank up or gave away his considerable royalty checks as fast as they arrived, and he sadly pulled a three year stretch in Angola starting in 1968. After that, things were never the same. He died of a heart attack in 1976. James Rivers, who's playing that wailing sax on today's selection, had the next release on the label, a sweet rendition of another Gospel tune, Just A Closer Walk With Thee, which would be his only release on Instant. The subject of the Second Annual Soul Detective Mystery Contest, he went on to make a bunch of other great records on small local labels like Eight-Ball, Kon-Ti, and JB's. He is still active as a jazz musician, and performs at Jazz Fest every year.

James Rivers, who's playing that wailing sax on today's selection, had the next release on the label, a sweet rendition of another Gospel tune, Just A Closer Walk With Thee, which would be his only release on Instant. The subject of the Second Annual Soul Detective Mystery Contest, he went on to make a bunch of other great records on small local labels like Eight-Ball, Kon-Ti, and JB's. He is still active as a jazz musician, and performs at Jazz Fest every year. Another character in the mold of Jessie Hill or Chris Kenner was a guy who Jeff Hannusch describes as a "street hustler", Raymond Lewis. He started out as a member of Earl King's bar band The Swans, and later on became the bass player for Huey Smith's Clowns. The three singles he cut for Instant are all great, but probably the most memorable is his politically incorrect original version of I'm Gonna Put Some Hurt On You, another song Shine Robinson would cover a few years later. Lewis recorded his own 'answer record', Coppin' A Plea, for Earl King on Warm, and re-united with Toussaint for one more single on Sansu in 1967. According to Earl, "Raymond's a kicks character, he's a humdinger, man. He's a Deacon in the Church now."

Another character in the mold of Jessie Hill or Chris Kenner was a guy who Jeff Hannusch describes as a "street hustler", Raymond Lewis. He started out as a member of Earl King's bar band The Swans, and later on became the bass player for Huey Smith's Clowns. The three singles he cut for Instant are all great, but probably the most memorable is his politically incorrect original version of I'm Gonna Put Some Hurt On You, another song Shine Robinson would cover a few years later. Lewis recorded his own 'answer record', Coppin' A Plea, for Earl King on Warm, and re-united with Toussaint for one more single on Sansu in 1967. According to Earl, "Raymond's a kicks character, he's a humdinger, man. He's a Deacon in the Church now." I think my favorite Instant singles, though, are the pair Toussaint produced on Chick Carbo (one of which became the second B side post way back when). As I said then: "Leonard "Chick" Carbo was, along with his brother Chuck, a founding member of the great New Orleans vocal group the Spiders... Unlike Chuck, however (who went on to create proto-funk grooves like "Can I Be Your Squeeze" alongside classic Mardi Gras "Second-Lines" well into the 90s), Chick's recorded output apparently ended here. Despite years of searching, I've been unable to unearth much more information about this golden-throated baritone, except for the fact that he died in 1998." The four sides that Toussaint composed for Chick (during his 'Naomi Neville' period) are, in my opinion, right up there with anything else he ever wrote.

I think my favorite Instant singles, though, are the pair Toussaint produced on Chick Carbo (one of which became the second B side post way back when). As I said then: "Leonard "Chick" Carbo was, along with his brother Chuck, a founding member of the great New Orleans vocal group the Spiders... Unlike Chuck, however (who went on to create proto-funk grooves like "Can I Be Your Squeeze" alongside classic Mardi Gras "Second-Lines" well into the 90s), Chick's recorded output apparently ended here. Despite years of searching, I've been unable to unearth much more information about this golden-throated baritone, except for the fact that he died in 1998." The four sides that Toussaint composed for Chick (during his 'Naomi Neville' period) are, in my opinion, right up there with anything else he ever wrote.  Art Neville, of course, needs no introduction. A big favorite of yours truly, one of his early Instant sides was also featured here way back in the day. Skeet Scat, the A side of that single is one of those good time nonsense songs in the fashion of Art's earlier Specialty stuff like Zing-Zing and Cha-Dooky-Doo. Toussaint's biggest success with Neville came, of course, with All These Things (Instant 3246) which is, quite simply, one of the greatest songs ever recorded.

Art Neville, of course, needs no introduction. A big favorite of yours truly, one of his early Instant sides was also featured here way back in the day. Skeet Scat, the A side of that single is one of those good time nonsense songs in the fashion of Art's earlier Specialty stuff like Zing-Zing and Cha-Dooky-Doo. Toussaint's biggest success with Neville came, of course, with All These Things (Instant 3246) which is, quite simply, one of the greatest songs ever recorded. One of the most under-appreciated of these Instant singles, the great Undivided Love by Eskew Reeder is positively da bomb, man. Reeder, of course, is none other than the flamboyant, unsinkable Esquerita, the man who taught Little Richard how to play the piano (among other things). He had come up as a Gospel singer out of Greenville, South Carolina, and cut an album's worth of rock & roll sides for Capitol in the late fifties. Banashak had signed him to Minit in 1962, and issued two singles that didn't do much before bringing him over to Instant the following year for two more. Check out Toussaint's back-up vocals on this one... unreal! Esquerita went on to record for a variety of labels without much success, and died broke in New York in 1986. His legend lives on.

One of the most under-appreciated of these Instant singles, the great Undivided Love by Eskew Reeder is positively da bomb, man. Reeder, of course, is none other than the flamboyant, unsinkable Esquerita, the man who taught Little Richard how to play the piano (among other things). He had come up as a Gospel singer out of Greenville, South Carolina, and cut an album's worth of rock & roll sides for Capitol in the late fifties. Banashak had signed him to Minit in 1962, and issued two singles that didn't do much before bringing him over to Instant the following year for two more. Check out Toussaint's back-up vocals on this one... unreal! Esquerita went on to record for a variety of labels without much success, and died broke in New York in 1986. His legend lives on. Speaking of legends, what more can I say about Emperor Of The World Ernie K-Doe? After Minit was sold off to Lew Chudd, Ernie made the switch to Instant for two more singles, before moving on to Don Robey's Duke label in 1964. Baby Since I Met You is an excellent Toussaint production of a song K-Doe wrote himself, that's got it goin' on. Nowadays, it's a later collaboration between these two men that's getting all the press, 1970's Here Come The Girls... Burn, K-Doe, Burn!

Speaking of legends, what more can I say about Emperor Of The World Ernie K-Doe? After Minit was sold off to Lew Chudd, Ernie made the switch to Instant for two more singles, before moving on to Don Robey's Duke label in 1964. Baby Since I Met You is an excellent Toussaint production of a song K-Doe wrote himself, that's got it goin' on. Nowadays, it's a later collaboration between these two men that's getting all the press, 1970's Here Come The Girls... Burn, K-Doe, Burn! Although the Instant label continued on after Allen Toussaint's stint in the service, things were different. Sax Kari took over as the producer for a while, and did some cool things with Chris Kenner like Wind The Clock and Fumigate Funky Broadway, before moving on and being replaced by Eddie Bo. Those 'higher numbered' 45s have become quite collectible as a result of Bo's involvement, as have later singles by guys like Lee Bates (who was Kenner's designated driver), but I think this early period is every bit as interesting, and deserves more attention.

Although the Instant label continued on after Allen Toussaint's stint in the service, things were different. Sax Kari took over as the producer for a while, and did some cool things with Chris Kenner like Wind The Clock and Fumigate Funky Broadway, before moving on and being replaced by Eddie Bo. Those 'higher numbered' 45s have become quite collectible as a result of Bo's involvement, as have later singles by guys like Lee Bates (who was Kenner's designated driver), but I think this early period is every bit as interesting, and deserves more attention. Allen Toussaint turned seventy years old this past January. Make no mistake about it, he is every bit as important to the evolution of New Orleans music as Louis Armstrong, Professor Longhair, Dave Bartholomew, Wardell Quezergue, Eddie Bo or anyone else you might care to mention. In the wake of Katrina he has, fortunately for us, been more active than he's been in years. Don't pass up the chance to go see him. He is living history, my friends.

Allen Toussaint turned seventy years old this past January. Make no mistake about it, he is every bit as important to the evolution of New Orleans music as Louis Armstrong, Professor Longhair, Dave Bartholomew, Wardell Quezergue, Eddie Bo or anyone else you might care to mention. In the wake of Katrina he has, fortunately for us, been more active than he's been in years. Don't pass up the chance to go see him. He is living history, my friends.So listen... I'll be thinking about you while I'm down there in The Town That Care Forgot (unless, of course, I forget...), and we'll do it all again soon.

Thanks for stoppin' by!

- red